by Ken Ibold

Each pilot rating or certificate is a hard earned trophy that reward pilots for their efforts, not with a shiny sparkle from a shelf in the den, but with heightened skill for flying the airplane. They stand as testaments to the pilots ability to eke utility out of the airplane safely.

But like trophies of the more conventional kind, they need to stay polished if they are to retain their appeal. Neglect leaves them dusty at first, and theyll soon tarnish if theyre ignored.

Inexperienced pilots are inundated with advice to adopt a use it or lose it attitude with respect to skills. After a point, however, some pilots begin to look at their airplane as a piece of machinery they already know how to use. Such well-ingrained skills, they reason, are such a part of their fiber theyre not in danger of skills atrophy.

To an extent, those pilots are right. But that attitude can also foster the growth of bad habits – the most insidious of which is the inability to accept when a flight is going bad while there is still ample time to cut your losses. The fact of the matter is that, for many experienced pilots, this is a difficult thing to do.

One pilot was flying a Piper Arrow from Tifton, Ga., to Greenville, N.C., on a January evening. He had held a pilot certificate for more than 12 years, accumulating more than 4,000 hours total time.

The pilot and a friend departed Tifton at about 4 p.m., bound for Pitt/Greenville Airport. About two hours later, the pilot called Washington Center when he was about 30 miles from Seymour Johnson Air Force Base – which put him about a half hour from his destination.

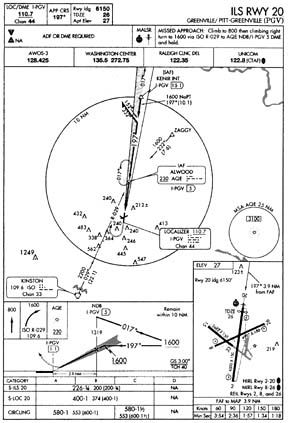

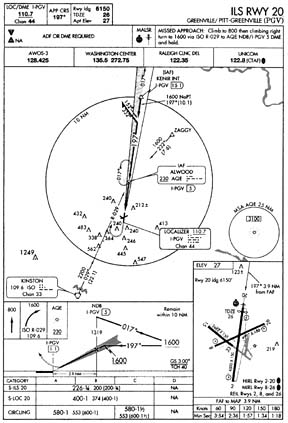

He filed a popup IFR flight plan and was given a clearance to descend from 5,500 feet to 3,000 feet and proceed direct to the Alwood NDB. Alwood was the initial approach fix for the ILS approach to Greenvilles runway 20.

He descended to his assigned altitude and held it for about a minute. The airplanes altitude then varied between 2,300 and 2,800 feet for the next seven minutes, despite the controller verifying the pilots altitude and reminding him of his clearance on two occasions.

The pilot crossed the fix outbound at 3,000 feet and was cleared to fly the full approach and to maintain at or above 1,600 feet in the procedure turn. The instrument approach calls for a minimum altitude of 1,600 feet during the outbound portion of the procedure turn and until crossing the initial approach fix again inbound. The fix is defined by the Allwood NDB or by a point on the localizer at 5 DME.

Weather at the time was reported as a 300-foot overcast, visibility one mile in light rain, wind calm, temperature 55 and dewpoint 54. Minimums for the ILS were 200 feet and three-quarters of a mile.

The controller turned the pilot over to the advisory frequency. The pilot acknowledged and began his descent as he flew outbound.

The NTSB report is vague on the pilots route at that point, but it appears that the pilot never began the course reversal at all. The airplane struck power lines at 35 feet agl, killing both occupants.

Aftermath

The wreckage was found 11.5 miles north of the destination airport. The wreckage was scattered along an initial path of 026 degrees, suggesting either that the airplane had not even begun the course reversal or had flown the outbound leg and was turning around to intercept the final approach course. In either case, it was outside of the 10-mile protected area.

The main wreckage came to rest in a small cemetery that contained five grave sites.

Examination of the wreckage and the airplanes logbooks turned up little in the way of trouble. The autopilot had been placarded inoperative, but the airplanes vacuum system was working and the engine was producing power.

The left elevator showed signs of a wire strike. The right wing separated at the wing root and showed a vertical slice about eight inches long, but that damage apparently was caused by impact with the ground.

Investigators found no sign that the attitude indicator, directional gyro or turn coordinator had malfunctioned. The altimeter was tested and found to be within limits. Furthermore, the pilots reported altitude during the approach was compared to the mode C altitudes received by ATC at the time and they were identical.

Investigators did, however, determine the landing gear was down and the flaps were extended two notches – a configuration one would expect when inbound from the fix rather than outbound.

The possibility that the pilot may have lost track of his position relative to the runway was reinforced by his logbook. Despite his high level of total experience, his instrument experience had not kept pace.

The pilots logbook showed 3,546 hours of cross country time and 324 hours of night experience, but he had gotten his instrument rating nine years after his private certificate.

Although he had recorded 135 hours simulated instrument time and 105 hours actual instrument time, he had logged only 10 hours of instrument time in the previous two calendar years, and none at all in the previous six months.

Toxicological tests determined the pilot had been taking an over-the-counter cough suppressant/antihistamine/decongestant that contained chlorpheniramine, among other active ingredients. Chlorpheniramine has been shown to cause drowsiness and have negative effects on complex cognitive and motor tasks. It also may interfere with the normal function of the middle ear, potentially increasing the pilots susceptibility to spatial disorientation.

However, the drug residue found by the tests suggest the pilot had taken a single normal dose within the previous 24 hours.

NTSB investigators are generally quick to assign blame to the effects of drugs in accidents, and this case was no exception. The board cited the pilots failure to maintain directional control due to spatial disorientation, with his lack of recent instrument flight experience as a contributing factor.

However, its also plausible that the pilot simply lost track of where he was relative to the airport. Procedure turns are somewhat uncommon in routine instrument flying in the southeast United States, and the pilots rusty skills may have tricked him into thinking he was inbound.

Beginning instrument students often lose track of their position relative to the airport. They tend to fly the needles rather than heading and can be surprised by vectors that seem perfectly reasonable to someone with more developed situational awareness.

Despite the accident pilots thousands of hours of flight time, his relatively young instrument skills likely had faded. Its unclear from the accident report whether the pilot knew he was flying into such low weather when he departed VFR on two-hour-plus trip.

How well prepared his was is, in retrospect, obvious: a broken airplane lying in the nighttime gloom of an empty field.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Aircraft Profile.”