The word “all” creates an impossible threshold. No brain can hold all information available, and yet FAR 91.103 does not let us off the hook. It requires that “Each pilot in command shall, before beginning a flight, become familiar with all [emphasis added] available information concerning that flight.” Additionally, it requires we know the “alternatives available if the planned flight cannot be completed.” At first blush, that may sounds like a simple task but to exercise an informed option, you have to know what services may be available along your route and beneath your present location. The more you know, the better your outcome will be.

Alexsander Markin

Most of us who travel from small airport to smaller airport recognize the importance of weather and fuel requirements, but the “alternatives available” is often neglected in our training. Instead, we’re focused on getting a weather briefing and knowing things like runway lengths, ATC frequencies and whether the destination has a restaurant. Too often, we learn the hard way that services at the small airports closest to our ultimate destination may not be available when we need them most.

All Airports are Not Equal

If you try to use a personal aircraft for reliable transportation, knowing the available services and facilities in the towns and airports you fly over may be the difference between abject misery or covering your basic needs, or the difference between arriving on-time or not at all. The information relevant to your alternatives should be available in the cockpit or, better yet, in your head.

Thankfully, the gadgets today make it fairly simple to build an exhaustive and up-to-date list of options, provided you download it all before launching rather than counting on an Internet connection at some distant divert field. Pilots who still rely on paper have a much larger task. Either way, you need to have a reasonable plan if you’re unable to arrive at your destination by air.

The one alternative always available when you can’t get there by air is to abandon your plans and abort the flight, or in the words of King Arthur in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, “Run away, run away.” However, it may not be prudent to head back to home base if weather behind you is worsening. This means you may need to land at the first available airport and hole up in whatever facilities are available.

Large-airport FBOs have air-conditioned lounges with free WiFi, fresh-baked cookies and color TV. Others don’t even have a portable toilet. Some airports have host communities with traveler amenities, like hotels and restaurants. Other times these essentials are many miles away. And there’s usually no crew car you can use, or even anyone on duty to sign it out. That presumes the FBO’s doors aren’t locked because you arrived after quitting time, and you can even get back through a locked gate to your airplane upon returning.

Ground Transportation

From a planning perspective, knowing about available ground transportation may be one of the more life-saving bits of information you can have. When the weather is iffy, it’s surprising how comforting it is to know that the airport just over your nose has options that could allow you to reach your destination.

If the town where you must land is sufficiently large, there may be rental car options. But the America I fly over has a lot of nothing. Even most of the larger towns do not have rental cars, and when they do, they aren’t parked at the airport, or you can’t get one when you need one, especially at 8 p.m. on a Sunday. An option that doesn’t fit your schedule isn’t much of an option.

Before my longer cross-country flights, especially in fickle weather, I make a point of knowing what the rental car options are for surrounding cities along my proposed route of flight as well as my alternative routes. I may not be able to make it to my destination, but I probably can make it to someplace where I have an option or two that will get me the rest of the way. The more options I have, the less pressure I feel to reach my destination by air and possibly fly in weather I might not otherwise consider.

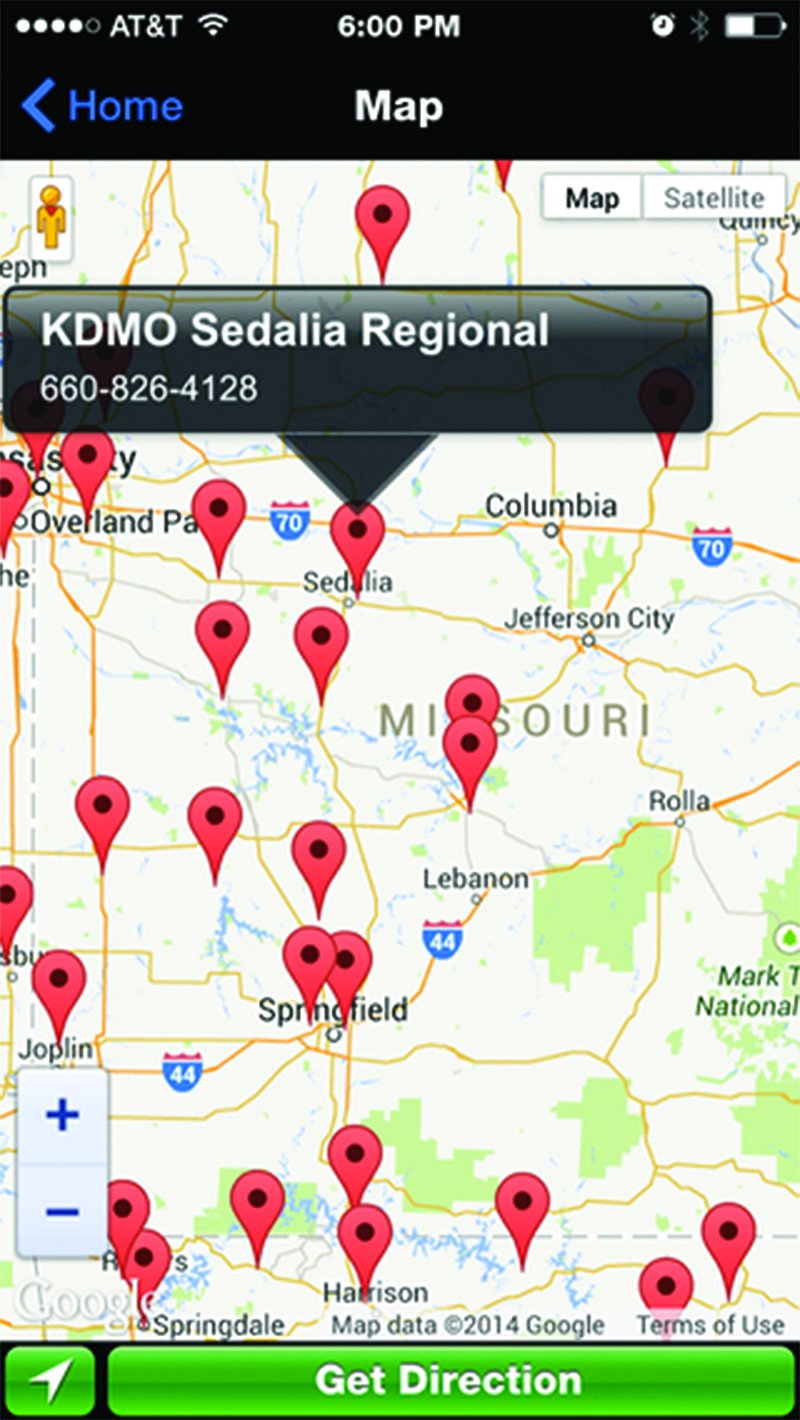

Airport courtesy or crew cars are frequently an option in places without rental cars. These forms of transportation salvation come in all shapes, sizes and subsidies. Some are provided by state aeronautics departments, others by an FBO or the host city, still others by pilots who frequently land at an airport and let other pilots know through the grapevine the secret hiding place to a set of keys. There are numerous sources for locating courtesy cars and, of course, there’s an app for that.

Knowing whether a courtesy car would be a useful option requires knowing beforehand what you can and can’t do with it. They often have restrictions. Some are only available for local use; others can’t be taken overnight. You may need to negotiate exceptions. Sometimes the cars themselves are self-limiting.

Webcams As Planning Tools

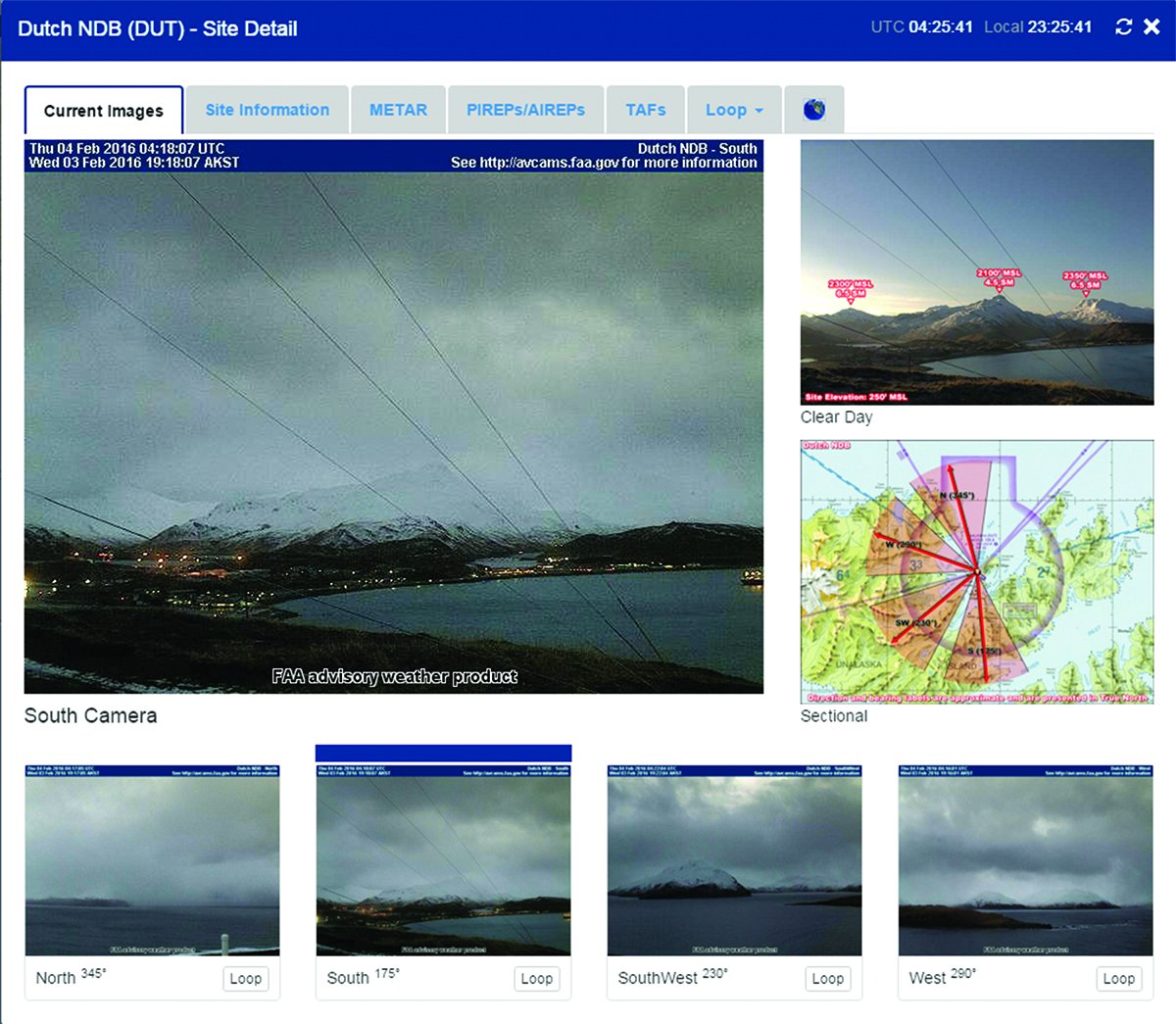

Many pilots know of the vast array of webcams put in place in Alaska and Canada to help improve pilot safety. All you flatlanders shake your head and wonder what kind of pilot would use a webcam for aviation weather, but I am here to tell you it is a prudent one.

Mountain weather is different than weather on the plains. By themselves, terminal forecasts (TAFs) and automated observations (Metars) for any given aerodrome are necessary but insufficient to understand the weather in canyons and mountain passes between airports. Sometimes airports are socked in by fog when the surrounding mountains are free of obscuration; sometimes it’s the other way around. The airport you are heading to may report clear and a million when the pass you need to get through is totally obscured.

On a recent trip, I had direct experience with three Oregon airports only 20-30 nm apart. Two were reporting ceilings greater than 6000 and even a non-airport aviation weather station at the top of the pass was reporting similar VFR conditions. But a quick look on a few webcams showed something quite different. A snow squall between reporting points showed up as a dark wall shouting, “Here be dragons!” Meanwhile, the annotated sectional chart on my iPad showed nothing but green dots indicating VFR conditions for every point along my route. The webcams told me the real, different story.

It’s easy to be lured into connecting the green dots on your EFB, hinting at VFR conditions, especially when the weather appears clear and stable. But before connecting them in changing weather, when fronts are moving or conditions unstable, a wise pilot will use available webcams along his or her route to round out “all available information.”

Webcams located at airports are also useful because they provide situational awareness beyond the aerodrome boundaries, information that amplifies what you see in the numbers. While the weather station on the field tells you current ceiling and visibility at the airport, a webcam pointed in a cardinal direction may show you a wall of clouds that likely will beat you to the destination. Airport webcams may also show the presence of snow, water or other details that will aid your situational awareness on arrival. Washington state, for example, has a site linking to numerous airport facility webcams.

In more remote parts of the country, there simply aren’t enough airports or weather reporting stations to give you a sense of the weather on the ground. Recognizing this dearth of weather stations, the Idaho Aviation Association’s Web site includes links to numerous webcams at various backcountry airstrips to help backcountry pilots like me fulfill the requirements of FAR 91.103.

Many other U.S. states have online webcam resources available through their transportation or aviation departments, weather services like Weather Underground, or private webcam hosts. If the resources above don’t give you what you need, just type a city or state name and the word “webcam” into your favorite search engine.

Treating Your Getthereitis

Even with good ground and backup option planning, getthereitis can be problematic, especially on longer trips or when you need to be at your destination at a specific time. Most pilots are mission-focused, so quitting doesn’t always fit our constitution, especially when we have compelling reasons to get to our destination. But we need to have as many outs for on-the-ground circumstances as we have when we are in the air. In my case, having a prepared list of ground transportation backup plans at intermediate airports keeps me from making bad decisions to stay in the air.

La Grande, Ore., for example, is a reasonably large city by rural western standards. Its name, translated from Spanish to English, means “The Big.” It has a college and a population over 13,000. But there are no rental cars. That said, they do boast a fleet of four (!) crew/courtesy cars. When the webcam on the highway between La Grande and Pendleton, Ore., shows my route over the Blue Mountains is blocked, I know I have a ground option.

The bottom line is if you get ramp-checked by an FAA inspector who might inquire about your compliance with FAR 91.103, it’s doubtful he or she will ask you about your alternatives if you can’t complete the flight. But I contend that non-traditional information sources like webcams and an informed understanding of your ground transportation and holing-up options makes you a safer pilot. That kind of planning information can empower you to do the right thing when weather or other circumstances dictate ending the flight early.

Mike Hart is an Idaho-based commercial/IFR pilot, and proud owner of a 1946 Piper J3 Cub and a Cessna 180. He also is the Idaho liaison to the Recreational Aviation Foundation.