Preflight inspections are kind of like landings: a good one takes some practice. As students, we were trained to walk around the airplane with a formal checklist, perhaps with our thumb pointing to the task at hand, so we wouldn’t miss anything. And in the rental/training environment, a methodical approach to preflighting what you’re about to fly has a great deal of merit: You never know who flew it last, the airplane’s condition afterward and what they broke until you look for yourself.

Things gets simpler if you ever transition into a flying club, partnership or outright ownership. The pool of potential ham-fisted pilots shrinks dramatically, and there’s usually some idea of who flew it last, whether they encountered any squawks and how long it’s been sitting since. Where and how it’s stored between flights also matters, with a single, dedicated hangar being the gold standard, a group hangar being somewhat less desirable and an open-air tiedown at the bottom of the list. Your preflight should be something less than an annual inspection but more than kicking the tires and climbing in. You always need to ensure the airplane is ready for the planned flight, but a little common sense goes a long way.

Keeping Your Distance

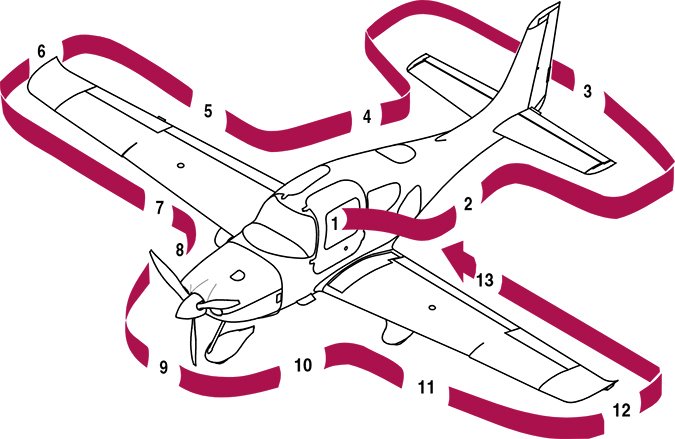

While we may not need to perform every preflight task before every flight, there are some items we should consider mandatory. Fuel quantity and quality come to mind, as does engine oil level. Then comes things like too many dead bugs on the windshield, tire pressure, prop nicks, loose components, control surfaces or fairings. Oil, fuel or hydraulic fluid leaks. These items are easy to check, and many can be verified while you’re walking to the plane on the ramp or pulling it out of the hangar.

In fact, examining the airplane with a critical eye from several feet away often highlights problems a close-up inspection might not find. Does the airplane’s parked attitude appear to be level, or is there a tire or strut that needs service? Do the control surfaces appear to be aligned as they should, perhaps with one aileron up and the other one down? Same for the elevators, if so equipped. Are there bird droppings on the pavement or the airplane itself?

We mention these kinds of things—details of which usually aren’t on the manufacturer’s recommended preflight checklist—because we firmly believe that a preflight inspection has less to do with following a formal checklist than it does a basic curiosity that begins with evaluating the airplane from a distance. There’s plenty of time to get into the checklist’s procedures.

Getting Your Hands Dirty

Depending on the airplane and your level of confidence in it, you may need some basic tools to properly preflight it. A fuel sampling cup of some kind usually is mandatory, as may be a screwdriver, pliers or a flashlight. Other items you may want to consider as part of your preflight toolkit include a tire pressure gauge, any specialized tool used, for example, to secure cowling fasteners, and some paper towels or rags. A good Plexiglas cleaner comes in handy for getting dead bugs and other dirt off the windows.

You’ll also want something to wipe down the engine oil dipstick after you check it, and perhaps to clean your hands after running them all over the airplane, checking things for their security. A helper/passenger will come in handy if a close inspection of the engine compartment is necessary and portions of the cowling need to be removed for access. You probably keep these tools stowed in the cargo compartment—except for the helper—if you own the airplane, but you may need to bring them with you if you don’t.

Doing a preflight correctly can mean getting your hands dirty. You may want to move things through their full motion ranges, wiggle them to check their security, run your fingers over propeller blades checking for nicks, and pushing and pulling to make sure everything is likely to stay attached.

Solving Mysteries

We like to think of preflighting an airplane as an exercise in solving basic questions. Does it have fuel? Oil? Are all the big parts attached? Is this an airplane you feel comfortable flying, and will it be adequate to the mission? Think of them as mysteries to be solved.

The bird nest on the opposite page? Its discovery was foreshadowed by an errant twig visible from the front of the engine. With that clue, additional investigation was necessary, uncovering the reason for the twig and its source. Without seeing that initial clue, it’s not certain the nest would have been discovered during the preflight inspection.

Other clues may not be so obvious. Even if there’s no liquid underneath the plane, are there any stains? What about the drains and sumps themselves? Any seepage? Streaks aft of the fuel filler ports? Where did any of this come from? Is this “normal,” or is it the first time you’ve encountered this condition?

Ask questions. Look for answers. Those answers may raise new questions. Channel your inner Sherlock Holmes.

Cutting Corners

Can you eliminate some or even most of this? Absolutely. If you’re about to mount up again after a four-hour cross-country during which the airplane performed perfectly, you didn’t hit anything and there’s no oil streaming down the cowling, yeah, you have better-than-average odds of being in an airworthy airplane.

If your storage facility is a private hangar to which you control access, it’s not likely you’ll need to wiggle much or look hard for missing parts if you know the airplane has been unmolested since its last flight. All the basic stuff usually still applies, though, unless you did something in the way of a post-flight look-see when parking it the previous time. But there are things you simply never want to ignore.

Fuel should be an obvious must-check item before every flight. If you’ve just refueled and are “confident” there’s nothing but good, clean fuel in your tanks, wait five minutes and then drain the sumps. Water and foreign material may take time to settle to the bottom of the tank, where the drain is, after being pumped in. Engine oil always is an obvious thing to check, even if the dipstick is too hot to handle after the last flight and there are no obvious oil leaks.

Depending on the season, we may be less concerned with somethings and more anal about others. Cabin heat isn’t a high-priority item during the summer in Florida, but it might be a no-go item elsewhere. An extra glance at the muffler and heat exchanger, or the combustion heater, during cold weather never hurt anything.

Preflighting the Cockpit

Once the exterior inspection is complete and depending on your mission, you may need to spend some quality time setting up the cockpit. Mounting your tablet and any accessories where its electronic flight bag application can be the most use to you is high on the list these days, as is ensuring it has power. Many of us also deploy some kind of ADS-B In receiver; it needs to see the sky and have a power source, also. All such items need to be mounted securely and checked for function.

If you have a panel-mounted GPS navigator, chances are it has a data base that may need updating. The time to do so is before starting the engine(s) and while all systems are shut down, especially the avionics bus. Many of us also keep charts and other resources on the tablet/EFB, but paper charts and any other documentation we plan to use on the flight need to be readily accessible. That’s what map pockets in the sidewall are for.

Some other, more mundane tasks also need to be accomplished before energizing the starter. Does the magnetic compass have fluid in it, and is it pointing more or less in the right direction? Do the fuel gauges match what you observed during your walk-around? Are all the loose items in the back seats or in the cargo compartment properly stowed (so they won’t become ballistic missiles in turbulence or a sudden deceleration)?

What is the vertical speed indicator reading? Note any error so you won’t chase it trying to maintain straight and level once airborne.

Process of Elimination

An airplane we know intimately and that’s been in a secure hangar since it was flown last week isn’t likely to need an intrusive preflight inspection. It’s reasonable—necessary?—to spend much more time on one you’ve never seen before that’s tied down on the rental line at a seaside resort airport.

Another way to think of a preflight inspection is as a process of elimination. There are certain things you must have to safely fly this airplane on this day. Do you have them? Are you confident they’ll work as intended? If you don’t have them, can you get by without them? That’s what a good preflight is for, to help answer those questions.