Many of us like to fly autopilot-coupled instrument approaches as a standard operating procedure. After all, it’s common to use the autopilot in cruise, so why not let it fly the arrival and approach, too? One reason is that it’s also common that pilots will come to depend on the autopilot to make up for shortcomings in confidence, skill or proficiency.

And like every other technology, autopilots have their limitations. For one, they have to be set up correctly—along with the navigation equipment—to reliably follow a heading and descend along a glidepath. Details like when to take over from the autopilot, how you might handle an equipment failure—if you notice it—and even whether to let Otto fly the missed approach or do it yourself need to be worked out ahead of time. That’s the short version of why we might want to consider hand-flying the approach. Let’s expand on them.

1. Busting Minimums

A very frequent rationale for flying coupled instrument approaches is that an autopilot flies more precisely than any human. Consequently, the logic progresses, if the weather conditions are at or near minimums, it’s better to let the autopilot fly the approach. A further corollary: It’s safe to fly approaches to lower minima using the autopilot than you are comfortable with or capable of flying by hand.

The first stipulation (greater precision) may in fact be true, but with a caveat: For any number of reasons, the pilot (you) may need to step in at any moment and take over by hand. If you find yourself on a coupled approach below your personal hand-flying minimums and then something happens to the autopilot, will you be ready to immediately take over and fly with the precision needed to complete the approach to minimums or fly the missed? If the answer is not “yes,” then it’s not safer to use the autopilot to fly approaches.

There are any number of things that can impede autopilot function or cause a disconnect. The complete list of failure modes depends on the brand and model of autopilot installed, just as the brand and model of navigation system interfacing with the autopilot can introduce failure modes as well. Possibilities include electrical failure, AHRS malfunction, attitude indicator failure, heading indicator failure, turn coordinator failure, accidentally or inadvertently touching the trim switch (in some models, bumping one side of a split trim switch will disconnect the autopilot but leave a flight director engaged, making it look like the autopilot modes are still engaged). Others include trim servo failure, GPS or VOR/localizer system failure, antenna connection corrosion, pilot activation of the wrong autopilot or nav system mode, airframe ice accumulation that impedes trim or control surface movement, turbulence, a right-seat passenger’s nudge on the control yoke or curious push of a button…the list goes on and on. Are you ready to identify a surprise failure and hand-fly the rest of the procedure, perhaps partial-panel or with degraded navigation capability? If not, you’re allowing the autopilot to take you somewhere you shouldn’t be.

2. Autopilot as a Crutch

Hang around the pilot’s lounge or internet chat rooms long enough and you’ll hear someone say, “I haven’t flown a lot of IFR lately, but the autopilot will take care of me.” For all the reasons we just listed above, this is a very bad plan. An autopilot is a very capable, very stupid copilot: It will do precisely what you tell it to do, whether that’s what you want to do or not, and it will do it with no ability to predict the future. In other words, it’s only as good as your ability to control it.

If you’re rusty on the avionics, on the gauges or on the glass, chances are you’re going to be behind the curve on the autopilot and the systems that drive it. This includes partial-panel flight because in many cases, loss of the primary attitude and/or heading indicators will disconnect the autopilot, leaving you to go from monitoring a coupled approach to identifying a failed instrument and transitioning to partial panel hand-flying while still flying the procedure to a landing or a missed approach—a recipe for disaster if you’re not very sharp flying by hand.

Some autopilots make this easier for you. Although generally considered less precise, the typically lower-priced rate-based autopilots (S-Tec, for example) reference a turn coordinator, not the attitude and heading indicators, so they are still usable in the most dramatic partial-panel scenarios. More sophisticated attitude-based autopilots will bail on you the moment the dreaded red Xs appear, a gyro dies or a heading flag drops on an HSI.

3. Complacency

You need to actively participate in a coupled approach. Some years ago, I had a flight student who had a long career as a bush pilot in Alaska, but had retired to the Lower 48 and decided a turbocharged Bonanza was a better way to get around down here than the Super Cub he’d been flying. Despite his superb stick-and-rudder skills, I could not get him to safely hand-fly the more complex Bonanza in the week I had available. My student’s response was that I had failed to recognize his “man-in-the-loop” concept of autopilot operation (a common term for this in the early 1990s). Trouble was, this pilot wasn’t in the loop at all—when it came to IFR he was a “gear up, autopilot on” type who from that point on pretty much let the autopilot do its own thing. He paid very little attention to what was happening on the instrument panel between autopilot programming updates. And he absolutely could not hand-fly the simplest basic attitude climbs and turns by reference to instruments. “That’s what the autopilot’s for,” he told me.

Pushing the buttons, then sitting back and watching for decision height and the runway environment won’t cut it. You (and your passengers) are not just along for the ride; you are still pilot-in-command. Do the same things you’d do if hand-flying the airplane. Complete cockpit flow checks and checklists. Make callouts for altitude, heading and vertical speed. Adjust power and airplane configuration where and when needed. Anything less and you’re being complacent. If you aren’t an active participant in the ongoing approach procedure, then you shouldn’t be flying a coupled instrument approach.

4. Autopilot Unfamiliarity

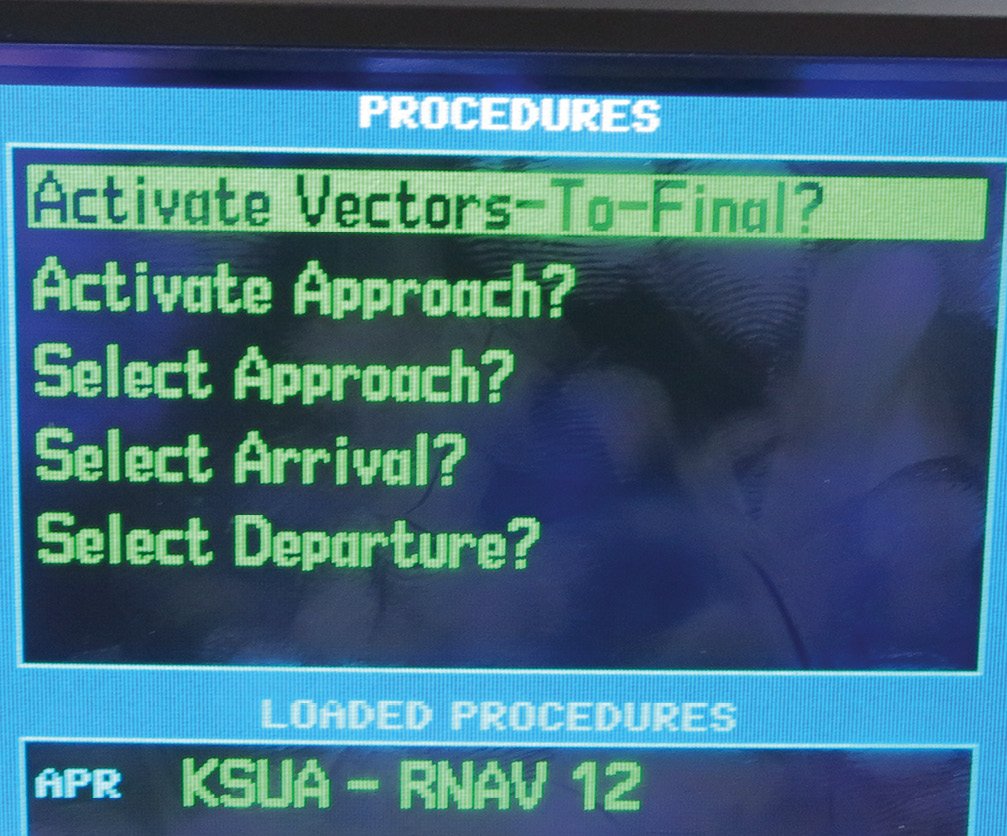

If you aren’t intimately familiar with how the autopilot works, you have no business letting it fly an approach. I’m guilty of impulsively pushing the wrong button at the wrong time, and I imagine you’ve done the same thing at least once. Several years ago, I flew a demonstration ride of the Garmin G1000 system in the then-experimental G36 Bonanza. Although the sky was severe clear and I was pilot-flying, my demo pilot in the right seat was definitely pilot-in-command of the avionics. Even then, we had one of those classic “What is it doing?” moments when trying to set up for vectors to a practice coupled ILS. If you ever find yourself asking that question, you know you need more time learning about the autopilot system.

Take the time to read the autopilot’s supplement—some are quite extensive—and to learn the tricks of interfacing it with the model of GPS installed. The same GPS can do different things with different autopilots, especially if the GPS is an early model or the autopilot design is more than a decade or so old. Understand and perform the full autopilot preflight check from the supplement, and know the system’s limitations. Some may only be able to intercept a glideslope from below, for instance, while others are certified only when the fuel load is balanced within some parameter in one wing compared to the other.

5. The Missed Approach

Missed approach procedures are predicated on climbing to a safe altitude, then turning in a safe direction to get away from terrain and other traffic. The autopilot/navigation system combination has no way of knowing how fast your airplane will climb on the missed approach segment because performance will vary dramatically based on airplane weight, environmental conditions and your piloting technique. Consequently, most autopilots will not fly the missed approach; you need to disengage the autopilot and hand-fly at least long enough to get the airplane configured for a climb. This can involve power, landing gear, flaps, retuning navaids, GPS manipulation (into and out of SUSPEND or OBS modes) and communication with ATC. That’s a lot to do while hand-flying the airplane, so you need to be ready for it.

Even if you break out and are in a position to land the airplane, you may have some control manipulation to do. Further, autopilots have the capability of “holding a little pressure” against the trim servos, meaning it’s not unusual for the airplane to be a little out of trim when you disengage the autopilot. Remember that, according to the FAA, in most cases coupled nonprecision approaches must be discontinued and flown manually at altitudes lower than 200 feet agl or 50 feet below the minimum descent altitude, and coupled precision approaches must be flown manually when descending visually below minimums.

Final Notes

Notice that except in the context of descending to lower minima when coupled than you would when flying by hand, I’ve not said much about autopilot failures. The truth is that most autopilot systems are very reliable, so operational problems are more often the result of operator error or failure of another system that affects autopilot operation. When they do fail, however, autopilots tend to go dramatically, with trim movements until the point that autopilot control force tolerances are reached. Then the autopilot disengages with a radically out-of-trim airplane.

In some of the most recent airplanes equipped with all-electric trim systems, there is no way to manually trim off the extreme pressures. This means you’ll have to complete the approach or fly the missed procedure by hand while fighting the out-of-trim condition. And you’ll have to do it with little warning.

Use your autopilot as the excellent cockpit aid that it is. But don’t let the autopilot take you someplace you cannot comfortably hand-fly if you had to. Don’t fly autopilot-coupled approaches for the wrong reasons.

- Set personal minimums based on your hand-flying capability. Fly coupled instrument approaches to the same minima, just in case you need to take over manually for

some reason. - Maintain a high standard of instrument currency before you use an autopilot.

- Know the autopilot limitations and failure modes so you can anticipate problems.

- Actively monitor the autopilot, flight and navigation instruments, watching for inconsistencies, disconnects or partial-panel indications.

- Don’t abdicate pilot-in-command authority to technology. Flying is still your responsibility.

- Take the time to thoroughly read and understand the autopilot, including its preflight check, then practice how the autopilot interfaces with the navigation systems on board.

- Be ready for hand-flying the missed approach or landing from minimums.

- Never let the autopilot take you somewhere you can’t go without it.

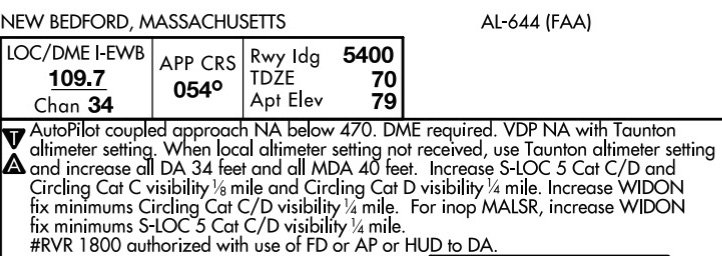

Some instrument approach procedures include a note stating a coupled approach is not authorized (NA). The approach navigation signal may be momentarily blocked at one or more points on the approach. Generally the blockage is temporary, like construction equipment.

The localizer and glideslope needles may “flicker” extremely briefly at some point on the approach, which a pilot can easily fly through (the needles re-center before you have a chance to try to reacquire), but which would cause an autopilot pitch and/or heading excursion if coupled.

Look for a related note on the instrument approach chart, but also check Notams because of the temporary nature of these approach limitations.

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.

Incredibly bad advice. While relying on the automation alone is not a good idea, the automation is what has reduced the accident rate among GA pilots.

Flying a coupled approach in hard IFR while practicing hand flying raw data when the weather is good is critical to safe flying in the 21st century. In jets, you would flunk your check ride if you didn’t use the automation to the fullest extent possible. I’m surprised you published this.

I totally agree with Arthur. Your article is irresponsible. Very concerning. We have a bigger issue with GA pilots not being proficient with their automation and trying to hand fly than the reverse.

I agree entirely. A landing is not a time for autopilot! Thanks, Steve

I get where the author is coming from, but I have a different idea on how I manage having an AP.

I try to fly about half of my approaches by hand and the other half with my AP for two equally valid reasons:

1. I need to keep my hand flying skills current.

2. I need to keep my memory of the “button pushing” skills current in regard to operating the AP in actual IMC.

I do think that proper use of the AP in IMC has greatly increased the safety of single pilot IMC operations, especially in busy airspace such as Class B. AP’s allow the pilot to concentrate on navigating and flying complex clearances from ATC while in these congested areas, which can be confusing to those of us who don’t regularly fly in those airspaces in low visibility conditions.

But I do agree that the overuse of the AP (even in cruise) can be a detriment to maintaining proficiency if not careful.