Long ago and far away, I was an instructor pilot (IP) on the U.S. Air Force/Northrop T-38 Talon, a supersonic trainer that first went into service in 1961. I was based at Laughlin Air Force Base, near Del Rio, Texas. Today, the T-38 remains in service with the USAF, as well as with NASA.

One of its nicknames is “The White Rocket”: You start the takeoff roll in full afterburner, raise the nose off the runway at 130 knots, let it fly itself off the concrete at 160 knots, raise the gear and flaps, allow the airspeed to hit 300 knots, and raise the nose to whatever attitude holds 300 knots. Might be 17 degrees nose-up. After pulling back the throttles to military power to save gas, you climbed to FL240 in about a minute—the darn thing will climb at 30,000 fpm—the altimeter just spins. Its performance is one reason the USAF Thunderbirds demonstration team used it, and it was in the original Top Gun movie, with a red star on the tail, masquerading as a Soviet “MiG.”

A U.S. Air Force major, a grizzled, gray-haired old pilot, probably all of 45 years old and with 3000 hours in the T-38, once told me, “The T-38 is an easy plane to fly, but it’s hard to fly well.” After flying it as a student pilot, as a copilot in the Accelerated Copilot Enrichment (ACE) program, and later as an IP, I realized the “old” pilot was right. The -38 is hard to fly well. Which makes it, among other things, a good trainer. I learned a few lessons in it, and wanted to share some of them that apply to almost any airplane.

RUNWAY WIDTH ILLUSIONS

I was on a cross-country flight in a T-38 as a second lieutenant student pilot when my IP and I came in for a landing at an unfamiliar airport. I flared for landing, and the IP, a very sharp former F-15 pilot, shouted, “I have the aircraft!” He jumped on the stick and throttles, slammed both throttles to afterburner, and—bam!—just like that, we landed. Hard. I had unknowingly flared too high due to the “wide runway illusion,” where it looks like you’re closer to the ground than you are because there’s more concrete visible out the front and sides. My home base had 150-foot-wide runways, and this one was 200 feet wide.

After we got out of the aircraft, the IP bent over and put his head under the wing and looked upward at the underside of the wing. When I asked him what he was looking for, sir, he said, “I just wanted to see if the gear was pushed through the wing.”

Lesson: A wider-than-usual runway looks very different when you’re down near it in the flare or roundout. Something to think about before landing. One-hundred fifty feet wide looks way different than 75 feet wide, and a pilot may flare high. Or a narrow runway, like the 50-foot-wide one at the Hermann (Mo.) Municipal Airport (63M), in Missouri, may give the illusion of being higher above the ground than you actually are, and a pilot might flare late, pranging it onto the runway.

Narrow Runway

A final approach to an unusually narrow runway or an unusually long one may appear as if you are too high. As a result, you may pitch the aircraft’s nose down to lose altitude. If this happens too close to the ground, you can land short of the runway.

Wide Runway

Meanwhile, final approach to an unusually wide runway may produce the opposite illusion, of being lower than you actually are. A typical response to this illusion is pitching the nose up to gain altitude, which can result in stalling above the runway and dropping it in.

Black-Hole Approach

This illusion has two variants, both of which occur at night: One involves an approach over water or unlighted terrain to a lighted runway beyond which the horizon is not visible. You may have the illusion of being upright and perceive the runway to be tilted.

The other involves a runway with few surrounding lights, which may produce the visual illusion of a high-altitude approach. If you believe this illusion, you may respond by lowering your approach glidepath. — J.B.

EMERGENCIES

As a T-38 IP, I once let a student “handle” an emergency. We were flying along on a so-called “zoom boom” ride, where we would demonstrate supersonic flight—flight above Mach 1—to the student. We would show how the control surfaces have less authority, how the stick becomes “mushy,” and you can “stir” it all around without the aircraft moving. Point out the jump in the airspeed indicator when it went to Mach 1.0.

Suddenly—fire light!—left engine. Whoa! I had only ever seen that in the simulator. I was in the back seat and said to the student, “Do you see that?” He said, “Yes, sir.” I was somehow calm (due to stupidity) and said, “Well, do the boldface,” meaning, “Perform the steps in the checklist that you have memorized, without looking at them.”

Well, he kinda froze, and did nothing, so I took control of the aircraft, and did the boldface items myself. I pulled the left throttle to idle and the fire light went out, with no indications of a fire. I left the throttle at idle, at the same time turning the aircraft 180 degrees aggressively homeward toward the base, instead of the northwest Texas desert where the student had it pointed. I declared an emergency with Rapcon (radar approach control), then I gave the aircraft back to the student. I figured he’d get some good experience, flying during an emergency, figuring things out. This turned out to not be the case.

He flew some, but as we got closer to the base, he wasn’t getting low enough soon enough, and seemed to be behind the aircraft, so I took over, put out the speed brakes and dove down—we were high and hot. I lined up for a straight-in single-engine approach to the center runway, the left engine at idle.

As we got closer and closer to the runway, the last mile or two, the aircraft sank and sank, and I had to add lots of power on the one engine to arrest the sink rate. I tapped the afterburner briefly a couple times. We were heavy, it was hot and we were down to one engine. I landed single-engine, uneventfully.

Lesson: An inexperienced pilot, while “qualified” to fly, may very well freeze up. So maybe don’t expect much from a new pilot. Several other instructors told me they couldn’t believe I let the student fly after the fire light came on.

AFTERMATH

Sure; the student froze—in full afterburner, going supersonic away from the base, with the fire light glaring—even though every single day the students practice the boldface items—they can’t get even a space, a dash, or one letter—much less one word—wrong. But I never should have let him fly.

We landed with our speed brakes hanging down. And you can’t raise ‘em with the engines shut down, so I was “busted”—there they were, hanging. In the T-38, after deploying the speed brakes (the “boards”) from the rear cockpit, to raise them from the rear cockpit the person in the front cockpit has to also check that their speed brake switch is “centered, then up.” But the student didn’t, and I forgot to verbally check that he did—my fault. So we landed with one engine on a hot day, heavy (because we had just taken off) with the incriminating boards hanging—thank heavens the boards aren’t very effective at slower speeds—but they were earlier, on long final.

Was I scared during all of this? You’d think I’d have known if I was scared, but I didn’t. But then I climbed down out of the cockpit. I saw the big fire trucks approaching quickly from two angles. That’s when it hit me that we’d had an “emergency.” My knees got really weak and wobbly under my G-suit and I stumbled just a little, almost falling down, but caught my footing. I felt choked up in my throat, and I choked back a mini-sob.

So I was scared, but didn’t realize it, and due to my bottled-up, tamped-down fear, I made mistakes. For example, I could have used that engine with the fire light, if I had to, but I thought of it as “dead.” I never checked to see if it worked.

A maintenance guy gave us a ride back to the squadron, and explained that the fire warning light was likely a false alarm, and the engine was probably fine.

Lesson: Yes, tamp that fear down, so we can think clearly—but go right ahead and think clearly, anyway, thank you.

“The key to successful management of an emergency situation, and/or preventing an abnormal situation from progressing into a true emergency, is a thorough familiarity with, and adherence to, the procedures developed by the airplane manufacturer.” So sayeth the FAA’s Airplane Flying Handbook in its introduction to emergencies. The AFH also identifies three psychological hazards associated with emergencies:

Acceptance

“[A] pilot who allows the mind to become paralyzed [by the emergency] is severely handicapped in the handling of the emergency.”

Fear

“The survival records favor pilots who maintain their composure and know how to apply the general concepts and procedures that have been developed through the years.”

Saving The Airplane

The desire to save the airplane, regardless of the risks involved, may be influenced by two other factors: The pilot’s financial stake in it and the certainty that an undamaged airplane implies no bodily harm. — J.B.

BEHIND THE AIRCRAFT

We young copilots in the ACE program would blast off out of our base in the T-38 on an IFR flight plan for an “airport-hopping” flight. We’d pop up to 3000 feet, drop into a nearby Air Force base, then drop into another really close Air Force base, then hop over to a nearby civilian airport, then back to our home base, all at 300 knots, all in an hour or so. The airports were a very short distance apart, and we only had VORs and paper approach plates and maps.

I was flying, and way “behind” the aircraft, befuddled, blasting along, and my copilot buddy in the rear seat noticed me flailing (how could he not?) and said gently over the intercom, “All right, let’s get that cross-check going.”

Lesson: Get and stay very proficient in the aircraft you’re flying, especially on instruments. After that embarrassing flight, I flew the T-38 as often as possible.

INSTRUCTORS BEARING GIFTS

An IP in the T-38 ACE program was a mischievous fellow. He would play little—or big—tricks on me to try to raise my airmanship and situational awareness levels. For example, we would take the T-38 out and do aerobatics in the MOA (military operations area). He told me one time, “Okay, let’s see you do a loop, there, Lieutenant,” but I noticed that he gave the aircraft to me right over a 10,000 foot-plus mountain peak. The bottom of the MOA was 11,000 feet MSL, but we needed 3000 feet agl or better for acro, and we would have had less than 1000. I said, “Sir, we are right over the mountain.” I heard, “Heh, heh, heh,” from the rear cockpit.

Another time he flew some high-G maneuvers, yanking and banking, to kinda “tumble my gyros” and get me lost in the MOA. He then pointed the aircraft to the north and said, “Okay, Lieutenant, take me home.” The compass showed a big S and that’s where the base was, but I knew we were pointed north, from the direction of the sun, where the mountains were, etc. I said, “Sir, I have to reset the gyros,” and I heard another, “Heh, heh, heh,” from the rear cockpit.

Lesson: Maintain situational awareness and don’t just trust the instruments. Where am I, where am I going, what’s my altitude and airspeed? If the altimeter reads 13,800 feet, and the mountain coming up ahead is 14,000 feet—hello!

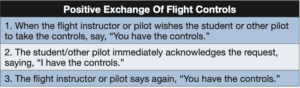

Any time there is more than one pilot at the controls, there’s a risk of miscommunication about who’s flying. Using the three steps in the table at right is highly recommended, and preferably should be accompanied by both pilots slightly wiggling the controls, providing tactile control exchange verification. —J.B.

WHO’S FLYING?

One time, another IP and I were flying a low-level route out in the middle of the desert, blasting along at 1000 feet agl and 400-some knots, following the routes we had traced on our maps clipped to our kneeboards. I was flying, then transferred control to the other pilot. I thought.

I said “You have the controls,” and to this day I don’t know if he responded, and “shook the stick,” and “chattered the rudder pedals,” which we did when transferring aircraft control. Suddenly, the aircraft was descending, and the desert floor was much more visible in the windscreen. I jumped back on the controls, said, “I have the aircraft!” and then raised the nose a bit. Soon, I asked, “Are you ready to fly?” He said yup, and we did it right this time. He later said, “I’m sorry, I didn’t hear what you said,” or something.

Lesson: Make very sure the aircraft controls are positively transferred, and there is no doubt as to who is flying, and who isn’t.

SITUATIONAL AWARENESS

Another copilot and I were flying a night cross-country flight in the T-38, and I was in the back seat for this leg, from Laughlin Air Force Base to Nellis Air Force Base outside Las Vegas. He was flying, briefed the Hi-ILS RWY 21L at Nellis, and we flew along at 0.9 Mach, fat, dumb and happy. However, just as he started the turn to join the 21 DME arc, he said over the intercom, “Uhh, can you, can you fly this? I’m way behind.” I was really watching the gauges, had my approach plate out with light on it, and said, “I have the aircraft,” and flew the approach.

It was very windy at Nellis—big crosswind— and we did a touch-and-go, and asked for and got a “closed pattern.” I pulled up, at night, toward the 7000-foot-high terrain to the west, and being scared of the mountains at night, I pulled hard to stay away from them. I pulled too hard, rolled out on downwind too close to Runway 21L, and I could see the big crosswind blow us even closer. We couldn’t make Runway 21L. I asked the tower if we could have 21R, and he approved it.

Lessons: Be ready to take over and fly at any time. The other copilot was quite sharp, a U.S. Air Force Academy grad, but for whatever reason, he “got behind” the aircraft. Mountains, obstacles—they are all on charts, and a pilot doesn’t have to “guess” where they are at night because they apparently stay where they were in the daytime. The mountains at Nellis were miles away from the pattern. Just like the chart said they were. Go figure.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

The point of all these stories is not that I or any other T-38 IP is ace of the base. Instead, it’s that pilots do dumb things, no matter what we’re flying or how regimented and time-tested is the curriculum. You can be doing 1.2 Mach or 0.25, and the same basic rules apply. I learned all this in the Air Force—you might learn it at Cheap Avgas Muni, but we all need to learn it sometime, somewhere.

Matt Johnson is former U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot and KC-135Q copilot. He’s now a Minnesota-based flight instructor.