Like it or not, winter weather is upon us here in North America. After a few brief weeks of not as much thunderstorm activity, we’re headed squarely into a a couple of months featuring widespread near-freezing temperatures and precipitation. From storing our airplane, to preflighting it, picking a route and ensuring our destination doesn’t have any slippery surprises, winter weather will have an impact on our operations, likely even if we stay in the pattern at a Southern California airport.

Some of us have spent all our summertime weather-watching glued to a Nexrad display (which actually isn’t an altogether bad way to deal with the season’s thunderstorms). The only good thing about summer thunderstorms is it shouldn’t be a surprise where they are and how fast they’re moving. Winter weather isn’t cooperative in those ways, however, and we may have become a bit rusty when it comes to looking for and evaluating weather information since last winter. Let’s try to fix that.

BASICS

We can start by thinking about freezing levels again, to help us find and avoid airborne icing. If your summer flying saw you routinely cruising in the teens and low flight levels, at or above the freezing level, you already know how important keeping tabs on this metric can be, especially when there is moisture about. As long as you’re in above-freezing air, you won’t accumulate airframe ice.

Another contrast with summer weather: Low freezing levels can impact a much broader geographic area, sometimes limiting the utility of trying to go around the weather you don’t want to fly in. In both cases, however, the amount of moisture in the air will have an impact, as will weather fronts. Just as in summer, warm fronts generally move slowly, often with reduced visibility in fog or haze, sometimes with little change over days. Cold fronts, on the other hand, can be just as problematic in winter, for the simple reason that cold air sliding in underneath a warmer, moist air mass generates precipitation. In winter, that precipitation can quickly turn nasty.

Pireps And Notams

Another thing we suggest you keep in mind about winter weather is the impact it can have on infrastructure: Those runways and taxiways aren’t going to plow themselves. Facility Notams take on greater importance after winter storms, since even if the runways are open, that doesn’t mean all the taxiways are, or that there’s open ramp space. Winter weather also can affect local navigation and approach aids.

Pireps should take on greater importance in winter, too, and not just during your preflight planning. For example, a forecast including an Airmet Zulu (icing) for your desired route and altitude is one thing, but that plus a series of pilots reporting the forecast icing is where you want to be in an hour should get your attention. We all probably need to give pilot reports more often, but that’s especially true in winter. The sidebar above has some examples.

The good news is the winter-weather observation and prediction products are better and more accessible than ever.

Route Planning

Your flight planning also takes on different challenges. Summer thunderstorms can effectively close an airport or terminal area for brief periods—and transform an approach into an E-ticket ride at Disney—but winter weather can have a much more widespread effect. Which means you need to consider alternatives and not just alternate airports when putting together your plan.

As always, carrying enough fuel to respond to contingencies is one way to ensure completing your flight as planned. Winter’s additional challenges can include industrial-strength headwinds, widespread low ceilings and airframe icing over large areas, like the Great Lakes. All of which means you need to think more seriously than ever about options before turning the key.

As always, those options include changing the conditions to your favor—civil aviation’s version of the Kobayashi Maru test—by staying flexible in your timing and routing. Go early. Go later. Go around the bad stuff and sneak in the back way. Remain at low altitudes to avoid the icing at higher ones. Stay at altitude in the clear as long as you can. Use the regional airport with snow removal equipment instead of the one closer to your destination that has cheap fuel but only one guy on a John Deere. Get a seat on Southwest, buy a bus ticket, or fly partway and rent a car. Reschedule for next week. Or don’t go at all.

If you absolutely, positively must make a flight into the teeth of a winter storm, you’ll want to plan it to avoid the worst weather and arrive when you have a reasonable chance of getting in. That can mean an intermediate fuel stop so you have enough fuel at the destination to hold or go to a distant alternate airport. But it mainly means using your planning tools to find a route and altitude that accommodates the weather and your needs, which simply may not be possible in all situations.

Inflight Updates

Although Nexrad radar is of limited usefulness in the winter, most of us these days have some means of obtaining near-real-time airport weather and Notam information while airborne. Use your en route idle time to keep tabs on your destination’s changing weather situation, and add a couple of nearby airports to your information gathering, too. The other airports may reflect area weather changes sooner than your Plan A. They also can help confirm what the other information you’re looking at is telling you.

Winter flying is similar to summertime in an important way: If there’s some weather-related drama going on nearby, it’s likely to come up on the ATC frequency. Icing is always a topic for discussion since anyone encountering ice is likely to let ATC know that’s why they want a different altitude. In our experience, interestingly, if one pilot on the frequency reports icing, it’s likely a couple of others will chime in with something to the effect of, “Well, now that you mention it…”

Such reports typically get passed along by controllers and go into the Pireps stream. But other reports can be even more helpful, like temperatures at altitude, along with cloud tops and bases. It’s one thing to be in wet clouds at 30 degrees F and quite another to be in severe clear at the same temperature. As always, it pays to listen to other pilots on the frequency as well as the controller to get the flick. Without pilot reports, the next person trying to make a go/no-go decision may not have all the information available.

Winter Risk Management 101

One good thing about winter weather is the colder, denser air will improve engine and aerodynamic performance. But that also means we’re more likely to use the airplane’s cabin heat system. It’s not a bad idea to give your single’s heat muff or your twin’s combustion heater a look-see, both for functionality and leaks. Winter also is the season when we may want to put fresh batteries in the carbon monoxide detector—it seems at least one GA flight each winter makes the news when the people aboard it pass out and fly until fuel is exhausted.

Winter weather means we may also want to consider some operational changes. For example, and as Bob Wright’s article beginning on page 4 highlights, it’s one thing to be forced to ditch in Lake Michigan in August, but it’s quite another in January. Even if you’ll only be out of gliding distance for a few minutes, the consequences can be far greater than just a couple of months earlier. Going around large bodies of water to avoid ditching in winter is a good risk management strategy.

Besides the impact winter weather can have on our operations, consider what extra equipment—warm clothing, a sleeping bag—we might want to carry in the plane. Consider also what happens to your ride home once you park it at the destination FBO. Will you be tied down outside during a snowstorm? Does the FBO have heated hangar space available to overnight your plane before your planned departure? What about TKS fluid—can you carry enough to get there and back—or preheating the engine? In the long run, it all may not matter, since in a few more months, we’ll be complaining about springtime crosswinds.

Winter Weather Graphics

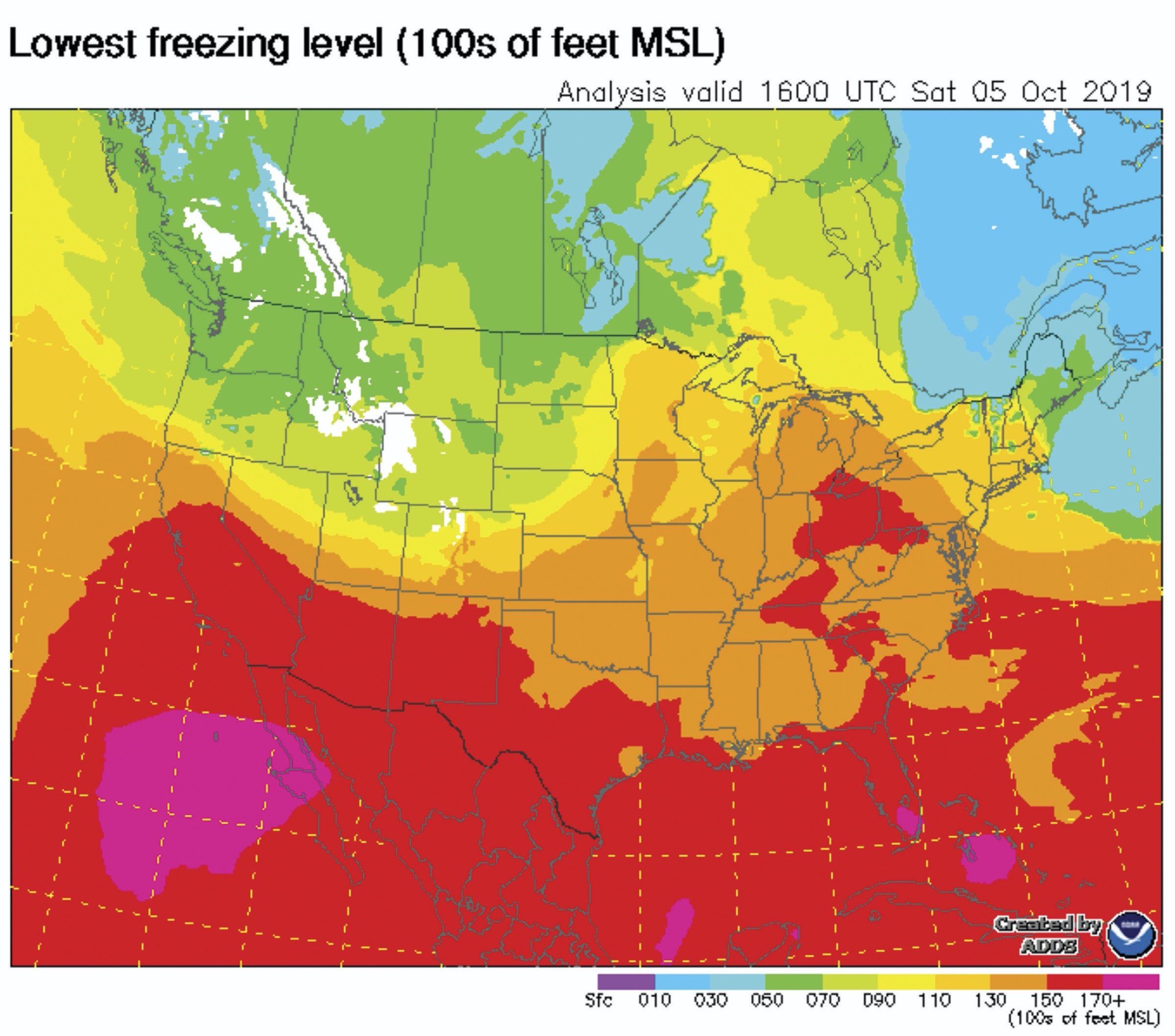

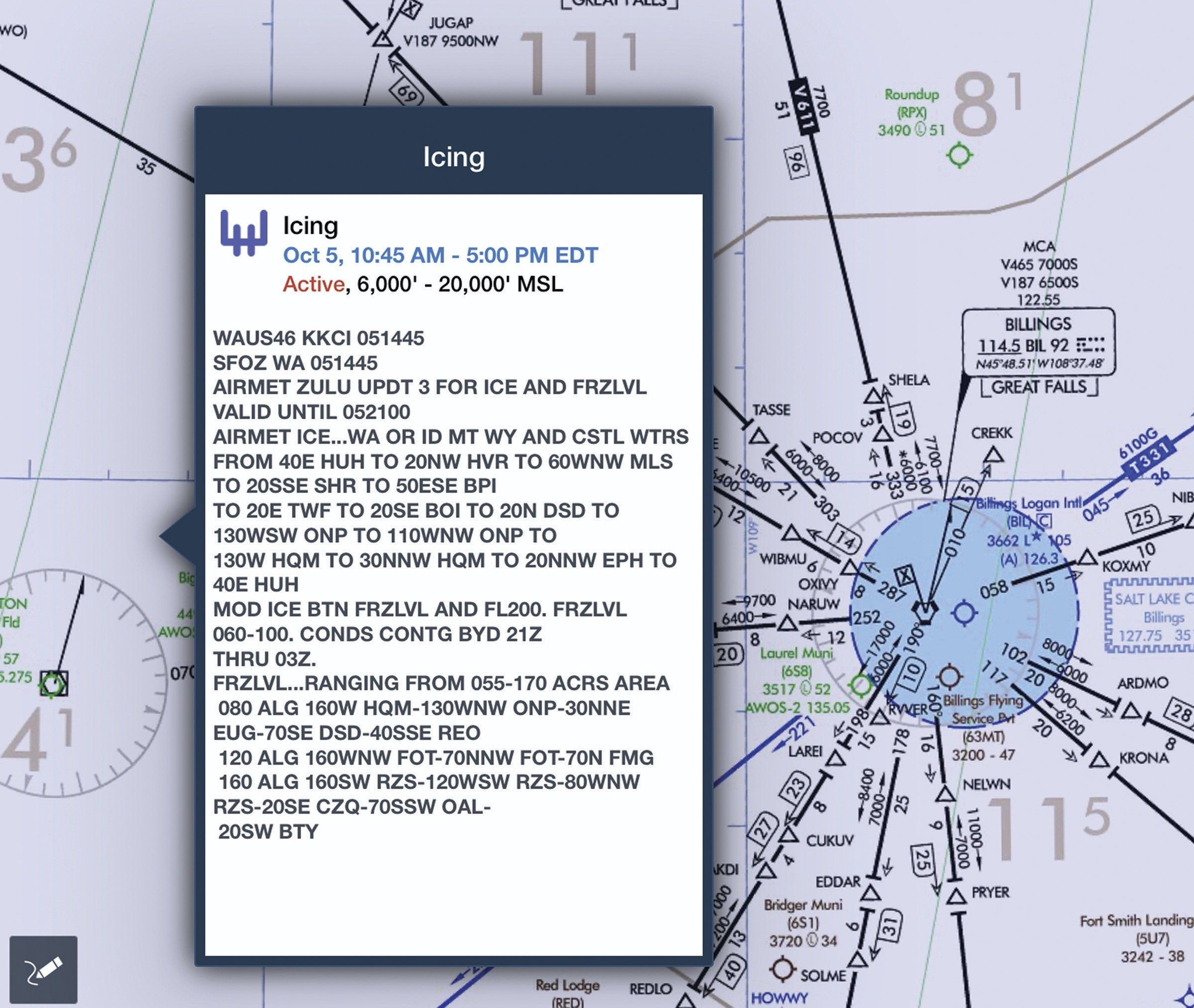

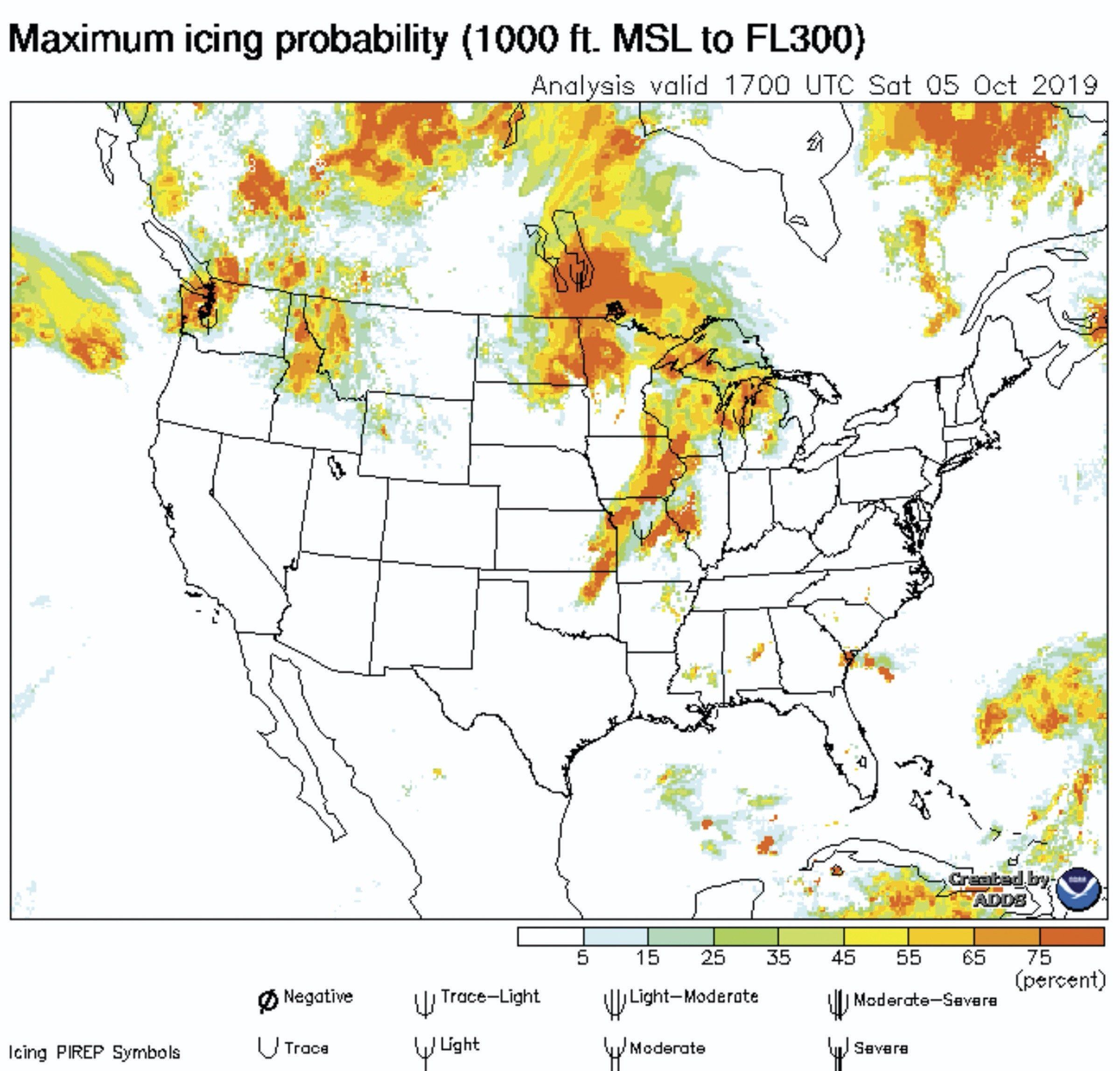

You may need to incorporate some different weather products into your preflight planning during winter. At top left is a plot presenting the lowest forecast freezing level accompanied by, at top right, maximum icing probability forecast.

At bottom are two ForeFlight screenshots, the left one showing details of an Airmet Zulu and the right one highlighting a pilot report of icing experienced by a Beech King Air 200. Both are excellent tools to help find the bad stuff in winter.

Braking Action Reports and Advisories

According to the FAA’s Aeronautical Information Manual, “When available, ATC furnishes pilots the quality of braking action received from pilots. The quality of braking action is described by the terms ‘good,’ ‘good to medium,’ ‘medium,’ ‘medium to poor,’ ‘poor,’ and ‘nil.'” When pilots report the quality of braking action by using the terms noted above, they should use descriptive terms that are easily understood, such as, “braking action poor the first/last half of the runway,” together with the particular type of aircraft.

When tower controllers receive runway braking action reports including those terms or whenever conditions are conducive to changing runway braking conditions, the ATIS will include the statement, “Braking Action Advisories Are In Effect.”