Scheduled passenger airlines in the U.S. have achieved an incredible level of safety. Domestic passenger operations under FAR Part 121 have achieved an unheard-of record: a near-zero fatality rate since 2010. Most of us presume general aviation operations under Part 91 never can approach this level of safety without draconian over-regulation. And most of us may be correct. It was never about the regulations, of course.

The airlines got to where they are by managing risk on a much larger scale than the typical general aviation pilot. Standard procedures, training and decision-making are well-defined in the airline world. And there are at least two pilots minding the store. Yes, some of that is required by regulation and, yes, history has shown the regulated tend to cut corners if fewer rules exist. But through well-established risk mitigation practices, even typical GA pilots can achieve the same levels of safety.

A Daunting Comparison

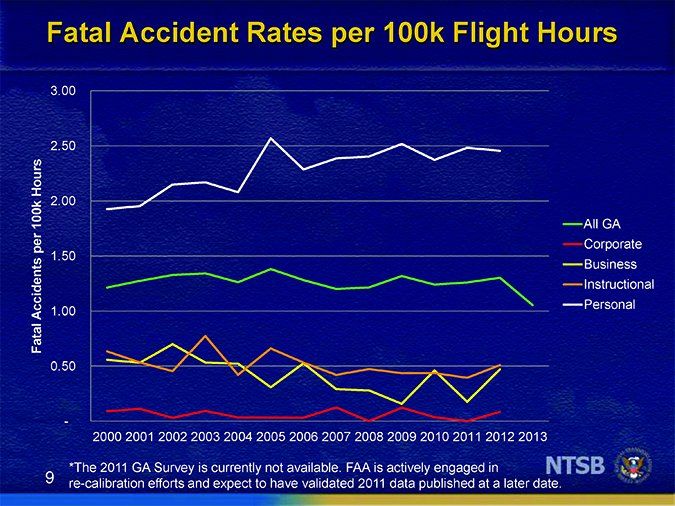

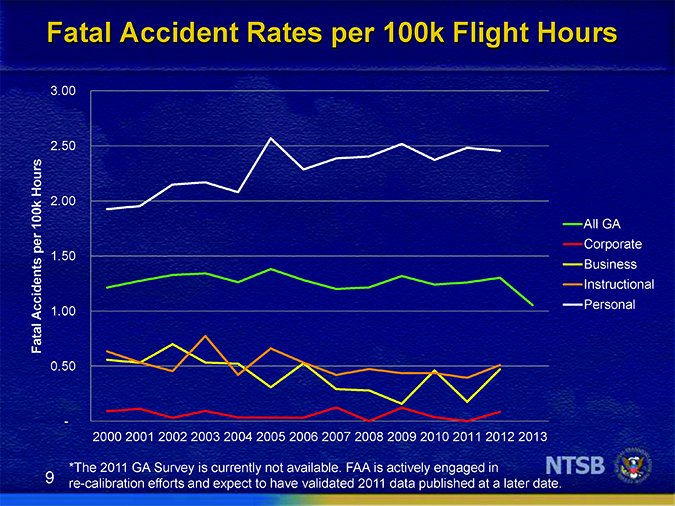

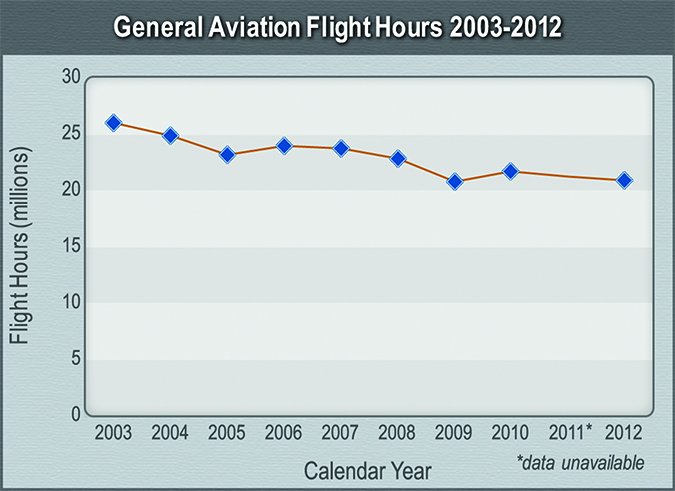

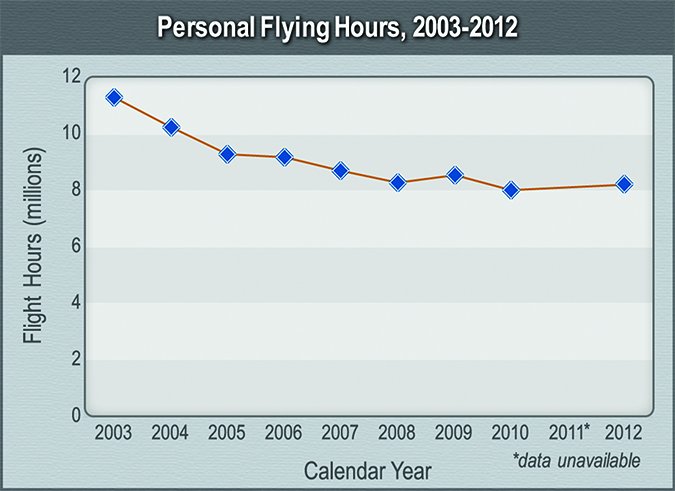

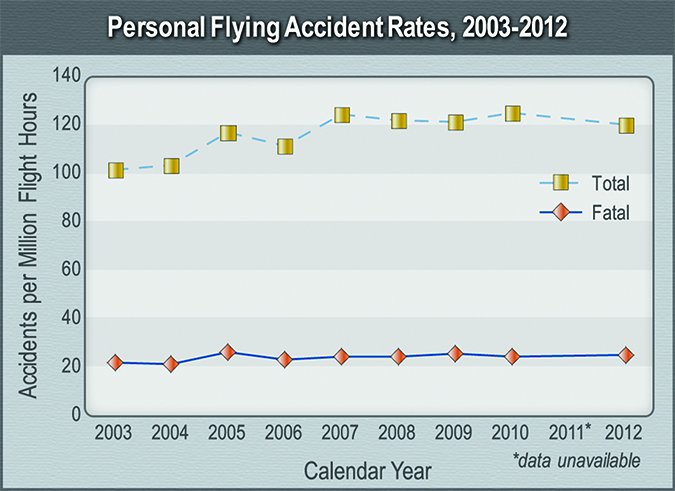

At first glance, it seems impossible for that part of general aviation we think of as personal aviation to ever come anywhere close to air carrier safety levels, which have been near-perfect every year since 2011. On the other hand, the NTSB graph below presents a different, more detailed picture for general aviation alone. The corporate aviation (that’s turbine-powered equipment, flown by professional two-pilot crews) fatal accident rate was also at or near zero for most years. Even business aviation (generally single-pilot non-professional crews) enjoys a relatively low fatal accident rate. Personal use general aviation, on the other hand, has a fatal accident rate above 2.0 per 100,000 flight hours—and that number has been relatively constant over the last few years.

It’s important to emphasize right away this disparity clearly illustrates segments of general aviation operate at or near airline safety levels, and they do it under Part 91 operating rules rather than the very stringent Part 121 rules that govern airline operations. If some Part 91 operators can achieve near-airline safety rates, one conclusion is the operating rules must have very little to do with it.

How’d They Do That?

While it always has been significantly better than general aviation, the U.S. domestic airline fatal accident rate was reduced nearly 80 per cent between 1996 and 2010 and has been zero in every year since. The change largely was due to collaborative, non-regulatory actions taken by the airlines and the FAA through voluntary actions devised by the Commercial Aviation Safety Team (CAST).

This ad hoc group was created in the wake of several fatal airline accidents during the mid and late 1990s. It quickly targeted fatal airline crashes and, most importantly, drilled down to determine the real root causes of these accidents. The group then created various procedural, equipment and information-sharing interventions designed to reduce risk. These tools were made available to the entire airline community. Since virtually all the U.S. airlines signed on to this effort, it was relatively easy for all of these interventions to percolate down to individual flight crews.

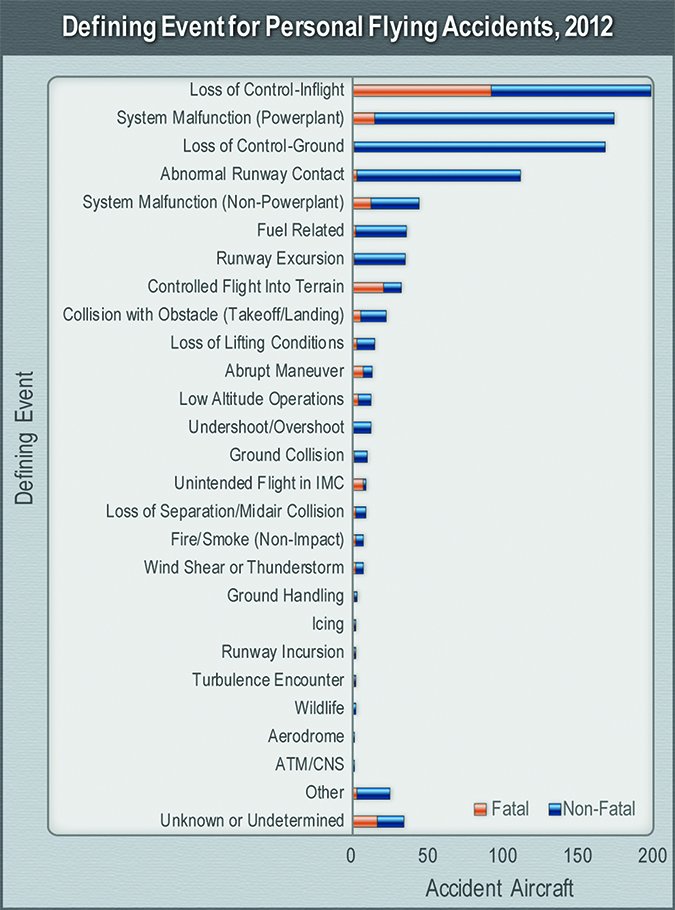

A similar effort was created for the general aviation community, but with far different results. The General Aviation Joint Steering Committee (GAJSC) was formed in 1997-1998 and included a wide variety of general aviation organizations. They also targeted leading fatal accident “causes” and came up with recommendations to address them. Significantly, the GAJSC initially did not, in my opinion, adequately analyze the true root causality of most general aviation fatal accidents. If they had, they would have discovered the huge role that poor risk management plays in them.

I tried to help this process along in 2001-2005, when I was the manager of the FAA’s General Aviation and Commercial Division, by creating the Industry Training Standards (FITS) program to modernize training standards, doctrine and curricula. The FITS program included risk management training as part of its core tenets.

I retired from the FAA in 2005 and the FITS program continued slowly. The GAJSC was reconstituted about three years ago and reorganized to emulate the success of the airline CAST effort. (Full disclosure: This magazine’s editor has served on a GAJSC working group.) The FAA also finally got around to changing the testing standards by instituting the airman certification standards (ACS) to replace the practical test standards (PTS). The first ACS documents, for the private pilot airplane certificate and the instrument rating, are to be released and go into effect about the time this magazine appears in your mailbox.

Breaching Boundaries

Don’t make the mistake of thinking I believe personal general aviation will ever achieve airline-like safety levels. By some measures, airline flying is 10 times safer than automobile travel, which in turn is seven to 10 times safer than general aviation. That’s two orders of magnitude difference between the airlines and general aviation. It’s realistic to assume there are safety barriers that can’t be breached due to the nature of general aviation and its flight environment. Two examples come to mind right away.

The first involves the vehicle itself. All Part 121 airlines must use aircraft certified under Part 25 of the regulations (or its predecessors). That means multi-engine aircraft are required. Practically, it also means turbine equipment. If you compare both the reliability and performance guarantees of multi-engine turbine equipment with single-piston-engine general aviation aircraft, it is like night and day. This doesn’t mean that single-engine piston aircraft are inherently unreliable or dangerous. If the risks are properly managed, equipment-related causes of fatal accidents can be reduced to a very small percentage of accidents.

Of far greater importance is the fact that every Part 121 airline crew consists of two highly trained professional pilots, as compared to GA’s single non-professional pilot who typically has far less experience and training. Even here, however, proper risk management could help level the playing field, but differences will still exist.

Part 121 as an Outline

The airlines manage risk in a variety of ways. The Part 121 regulation provides a floor, but most airline operations exceed these regulatory minimums in most areas most of the time.

One area where airlines typically operate at the regulatory minimums is in required fuel reserves. Airliners burn prodigious quantities of Jet A and if more fuel is carried than necessary, it affects specific range. This costs lots of money and the chief financial officers at airlines are acutely aware of this. However, taking only that fuel which the regulations require could result in increased risk. To manage this risk, the airlines take advantage of the rules in Subpart U of Part 121 regarding Dispatch and Flight Release requirements.

Every airline crew is backed up by dispatchers and flight operations support. These entities help ensure that the fuel aboard is sufficient to not only reach the destination and any required alternate, with 45 minutes more, but are also sufficient to cover any risks due to weather, air traffic delays or other contingencies. The fuel requirements and associated risk is one obvious area where the airlines’ bottom lines could conceivably conflict with desired safety results, yet except in very rare instances this conflict rarely creates a bad outcome.

Part 121 Risk Mitigation

The above example on fuel reserves is atypical of how Part 121 operations work. Let’s look a few more examples of how airlines manage risk and then we can see how this might play out with a general aviation operation.

Aircraft performance margins: Part 121 is very specific regarding how much extra margin must be applied to calculated aircraft performance. For example, FAR 121.185 requires the calculated landing distance must allow a stop within 60 percent of the effective runway length. No such limitation exists in Part 91.

Effective training: Two Part 121 subparts address flight crew training programs and qualifications, including initial and recurrent training, plus initial operating experience requirements. Crew resource management (CRM) requirements have resulted in major safety improvements by exchanging the old paradigm that the “captain is always right” with more collaborative actions by the crew and others.

Progressive experience: Airlines have learned the hard way that experience matters and Part 121 requires captains transitioning to new equipment to increase their landing minimums during their first 100 hours in that type. Other rules require routes and airport qualifications, and specify crew-pairing requirements and minimum training times.

Managing human factors: Part 121 also prescribes rest and duty time limits for crew and requires airlines to implement a fatigue-risk management system.

Your Own Airline?

It might seem impossible that a lowly Part 91 operator can achieve a goal of zero fatal accidents. But if we take some simple steps—avoid bad weather, carry enough fuel, ensure our aircraft are properly maintained and engage in regular, realistic training—we can usually have a long, healthy and safe “career” flying personal aircraft. In fact, it seems each month the FAA is recognizing a GA pilot for 50 years of safe flying, the Wright Brothers Award.

Achieving such a goal doesn’t require a byzantine set of rules laid down by a faceless bureaucracy, but it does require some common sense. To get to that level of safety, understand and recognize the warning signs of increased risk, then take whatever steps are necessary to mitigate the risks. Sometimes even the airlines cancel a flight, for fatigue, mechanicals and/or weather. So can you.

Robert Wright is a former FAA executive and President of Wright Aviation Solutions LLC. He is also a 9600-hour ATP with four jet type ratings and an a flight instructor. His opinions in this article do not necessarily represent those of clients or other organizations that he represents.