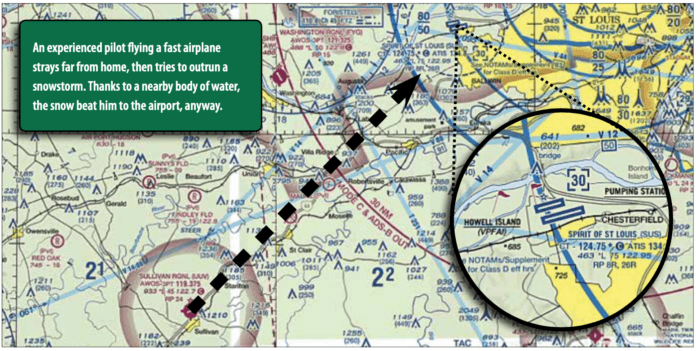

It was a December afternoon at Spirit of St. Louis airport (SUS), about 1400 local time. Sunny, with scattered clouds, cool. The weather forecast had the word “snow” in it, starting about 1800, which would be after dark, but right now it was sunny. Snow? Seemed like a long way off.

Turns out it wasn’t. I incorrectly reasoned that since I would only be doing touch-and-goes at airports located maybe 25-30 miles from SUS, if the weather started to get bad, I could quickly return home and be on the ground before, well, before what happened…happened.

Turns out the weather can change quickly—who knew? Plus I boldly flew a little further away from my home field than 25-30 miles. This was some years ago—now I’m older and not so bold.

YOU MOVE TOO FAST

I had this fast little two-seat high-performance experimental airplane that could cruise right along at 175 knots, “no sweatskies”—it could scoot. Which, I found out, may not get a person out of trouble, but can get a person into trouble. You can fly really fast right into bad weather where, if a person were flying something slower, they’d see it coming, and coming, and coming, like the steam-roller in that Austin Powers movie, and they’d turn tail and skedaddle.

So there I was, flying along fat, dumb and happy, quickly entering various airport patterns, all of them non-towered fields, and doing touch-and-goes. Some of the nearby airport names—Cuba, Mexico Memorial, Warsaw—make it sound like I was flying internationally.

Another problem with fast airplanes? You can go a long way the wrong way, quick as a bunny. The snow clouds were forming and starting to spit lightly in my face as I did touch-and-goes at Rolla National (VIH), which sits out in the countryside about 60 nm from St. Louis.

I looked through the lightly falling snowflakes drilling me right in the face, down at an aircraft turning off the runway toward the FBO at Rolla National. I heard the pilot say on the CTAF he was a full stop, and would remain overnight.

I got a kinda “warm fuzzy” feeling, picturing that pilot and maybe his wife, having hot chocolate inside the warm, lighted building, watching the snow falling outside the window. Maybe how they wanted to wait until the snow passed before flying, you know, be smart, be conservative. To me it was an “all-American” feeling, like I get near Thanksgiving or Christmas, looking at the airport and that airplane—the snow falling, me doing touch-and-goes, a lighted little FBO that kinda looked like a lighted cabin in the snow on a Christmas card.

In the worsening snow.

I did one more touch-and-go as the snow fell. One more too many, it turned out. That warm, fuzzy feeling? Turned out what I had was a warm, stupid feeling.

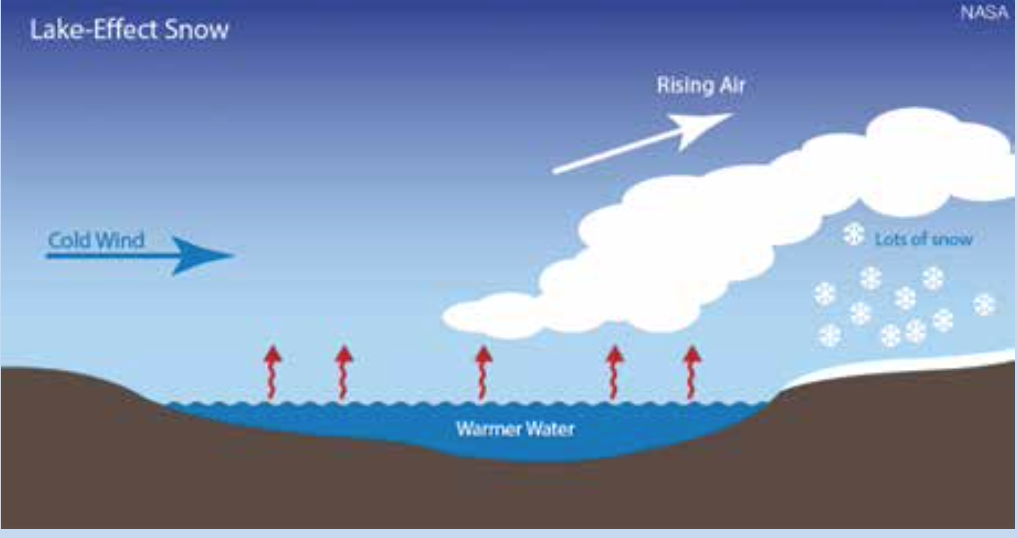

“Land and water surfaces underlying the atmosphere greatly affect cloud and precipitation development,” says FAA Advisory Circular Aviation Weather (AC 00-6A). But we knew that, from ground school. What we often forget is that such interactions can happen on scales much smaller than like the U.S. Great Lakes.

Cold Weather Effects

As cold, dry, stable air flows over relatively warm water, “the air is heated and moistened, and stability decreases,” according to Aviation Weather’s successor, AC 00-6B. “Shallow cumuliform clouds develop with low tops. The strength of the convection increases with increasing temperature differences between warm water and cold air, increasing wind speeds, and decreasing relative humidity within the cold, dry air.”

Warm Weather Effects

Warm, moisture-laden air flowing over relatively cold water brings different conditions, but they’re no less of a problem: low fog. As that air is cooled its moisture content condenses, forming clouds. A nearby, downwind airport can experience low ceilings and reduced visibility, even if upwind airports are reporting severe clear and the area’s predominant weather is good VFR. — J.B.

YELLOW MEANS CAUTION

On the go out of Rolla, I thought, “Man, this snow is really picking up. Perhaps I should go back to Spirit direct, instead of doing any more touch-and-goes at airports along the way.” You know, “be conservative,” beat the coming snowstorm. Even though I was in a snowstorm, I thought it was just light snow.

I looked down at the EFB on my leg and saw the entire screen had, curiously, turned light yellow. I thought that meant that there was an obstacle nearby. I tapped the screen, but couldn’t clear the yellow color. I had seen the screen go yellow before if I selected “full screen” when it depicted an obstacle, I thought I remembered.

But I was busy flying, and couldn’t fool with the iPad on my leg. I tried to fly, glance down and tap the screen and clear the yellow color, but couldn’t. I could still read the map through the yellow tint. So I made a magenta line direct to SUS.

I zoomed out the iPad screen and suddenly saw the yellow tint on the screen was not an obstacle. It was weather—filling the entire screen with yellow. Which is why I couldn’t clear the screen. My heartbeat way increased. Now I knew the yellow was light precipitation, plus I could also see it out the windscreen in my face—snow, lots of it, getting heavier. I flew through the snow, and the sky got darker, and darker. That forecast snowstorm? I found it.

I glanced down at the iPad, then up, down then up, and saw Sullivan Regional airport (UUV), just ahead, 4000 feet of beautiful concrete, weather clear. I thought, “I could land there—maybe I should land there—stay overnight, let the snowstorm pass.” Then I thought, “But where would I stay? Plus, my airplane will be snow-covered in the morning.” These were my idiotic thoughts. Then poof! I was past Sullivan, ripping along into thickening snow back toward Spirit.

And toward a lowering and lowering ceiling of gray and black-colored clouds. I thought if it gets worse, I’d turn around go to Sullivan. Fighting off mini-panic, I widened the ForeFlight map view further, and saw a big horseshoe-shaped red-colored band of weather right behind me. Red!? Where the heck did that come from? Out of nowhere. A minute ago, it wasn’t there. Now it was.

Our March 2020 issue featured a cover story on special VFR, pointing out how useful it can be. Some important reminders:

1. Pilots must request an SVFR clearance; ATC won’t offer it (although controllers may hint at it: “Is there anything special we can do for you today?”).

2. An SVFR clearance is granted on a traffic-permitting basis. IFR flight operations take precedence, and your clearance to enter or leave controlled airspace may be delayed for this reason.

3. SVFR clearances are available in Class B, C and D airspace, plus Class E surface areas only. ATC provides separation between SVFR flights and IFR operations. Regardless, ATC does not provide separation after an aircraft leaves the airspace on an SVFR clearance.

4. Since the pilot must remain clear of clouds, an SVFR clearance will not include a specific altitude. The clearance may include an instruction to fly at or below a certain altitude, due to other traffic, but that altitude will permit flight at or above the minimum safe altitude.

IT GETS INTERESTING

I couldn’t turn around and go back to Sullivan now if I wanted to. The red horseshoe-shaped weather band was huge, kinda corralling me to the northeast. The weather color on the iPad ahead was yellow, and then green. And then red again past that. I looked at Spirit on the chart and saw a red dot. IFR. I wasn’t instrument-current, and I had no flight plan. What to do? I can’t do a 180 into the red death clouds, and I’m not “legal” to go to SUS.

My mind raced. I didn’t want to get “violated” by the FAA, which, at the time, scared me worse than the snowstorm. There was no time to think—the weather was pushing me. I decided to race back to SUS—it was so close, minutes away! I bet I can make it—I’ll worry about “legal” later, I thought. I followed the magenta line toward Spirit.

The ceiling was dropping fast, and the snow was getting heavier, but I could see the ground underneath and ahead clearly. I read the sectional’s maximum elevation figure. If I could stay above that and under the ceiling, I was safe. Turns out I could, barely.

I scooted along just below the ceiling at about 1500 msl. I was using every one of the little speedster’s knots, throttle wide open, pitot heat and all my lights on, heart beating pretty fast. I called up the SUS tower, told them I was about 10 miles west, with the weather.

The response? Spirit-crushing: “Spirit of St. Louis airport is now IFR, unable VFR traffic, remain clear of the Class Bravo airspace, contact approach.” The tower guy was no help at all. Zero. Whoa, I wasn’t ready for that. What to do?

I continued flying a straight line to SUS, as I didn’t really have any other ideas. The only good weather was in that direction. I called St. Louis Approach, and said I was inbound to SUS, but was told to contact them by the tower. Approach: “Remain clear of clouds and the Class Bravo airspace.” Thanks for the help, folks.

OUR BLESSED LAADY OF THE MAGENTA LINE

Out of ideas, I continued flying the magenta line toward SUS, getting closer, closer. I was only a few miles away now, but all I could see was the ceiling above me, whiteness ahead, white ground flashing beneath me, farmland and scrub land, and now the Missouri River. Then I suddenly saw the field! The airport was smack-dab ahead—right where the magenta line said it would be. It appeared out of nowhere before my eyes, and boy, did it look different from when I took off.

The runway was just a white stripe, which blended in with all the other white on the ground. Everything was white—the ground, the runway, the taxiways, the tower and airport buildings. When I took off it was sunny, and the ground was green and brown.

As I turned to parallel the runway, I told Approach I had the field in sight, trying to sound calm, cool. I held my breath—I was ready for something like, “Possible pilot deviation; advise ready to copy a telephone number.” But they told me to call the tower. I keyed the mic, trying to sound cool, telling the tower I was two miles south of the field, runway in sight, requesting a full stop on Runway 26 Left.

Tower cleared me to land, and I landed safely. While on the runway on landing rollout, I again held my breath, thinking I was in big, big trouble. I had just landed VFR at a Class D airport when it was IFR, a big red dot staring at me on ForeFlight. I tried to quickly come up with “a story” in my head, but drew a blank.

Spirit tower finally spoke: “We had to treat you like an emergency aircraft.” My mind again raced. I could get violated. In fact, I am violated; the FAA is waiting at my hangar. They have their special FAA scissors, to cut up my license, and maybe an FAA sewing kit to sew back on the strip cut from my shirt tail when I soloed 30 years ago. Maybe they keep those shirt tails. Probably not. That would be weird. But it’s the FAA, so….

Even though full of fear, I had another fleeting thought: The tower didn’t treat me like an emergency at all. I was running scared from that snowstorm, just trying to get on the ground, but when I first called them, the tower controller sounded a little angry, irritated—and turned me away, told me to contact approach, stay clear of Class Bravo airspace. No help there at all.

I snapped out of that thought—I knew I was dead—and continued the landing rollout. I finally keyed the mic, and tried to sound scared and humble. Oh, I was scared, all right—of the tower, approach control, the FAA—everything except dying in a snowstorm.

“A pilot would rather die than sound bad on the radio,” a buddy of mine once told me. Sadly, at that time, he was right. In my best glad-to-be alive voice, I said, “Tower, that snowstorm came up out of nowhere!” I tried to sound scared, grateful. The tower wasn’t having it. They snipped, “Yes; we know that,” but said nothing further. So I taxied to my hangar and shut down. There seemed to be something wrong with my knees, I found. They were a little wobbly as I stepped onto the ground. Onto. The. Ground.

Pilots learning to fly nowadays have an easier time of it, in some ways, than in the past. Using a full-featured electronic flight bag (EFB) app on your portable device, you’d really have to work at it to get lost. It’s not like in the “old days,” when you had to read a paper map strapped to your leg that you wrote on with a Sharpie. Those were not the “good” old days, by the way. They were just old.

THE SHOULDAS

Later, I found out from another pilot, an airline pilot who got caught in the snow in Missouri like me when he was a CFI, that the Missouri River creates a “river effect.” He said this causes sudden snowstorms, like the “lake effect” snow in Chicago. About lake effect snow, the Internet says, “Heavy snow may be falling in one location, while the sun may be shining just a mile or two away in either direction.” Roger that, same with the “river effect” snow, just on a smaller scale.

What lessons did I learn from my little adventure?

• Fly with local pilots. I probably would have learned about the local “river effect” snow.

• Get current on the instruments, so I can just pick up an IFR clearance in the air.

• I should have landed at Sullivan airport, or Rolla, and waited out the weather. Who cares where I sleep? Safe is better.

• I should have asked for an SVFR clearance back at Spirit.

• I shouldn’t have gone so far away from my home field with bad weather approaching.

• And I should have known what it means when the entire screen turns yellow on ForeFlight.

Something else I learned? It sure is nice to be on the ground, inside a hangar with the door shut, in a snowstorm.

Matt Johnson is former U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot and KC-135Q copilot. He’s now a Virginia-based flight instructor.