by Perry Wilson

I decided to make my preflight inspection the day before I was to embark on a flight from Ontario to Alberta. Since buying the Piper Malibu new 17 years earlier, I had a pretty good understanding of the need to stay on top of its condition.

I intended to make a thorough preflight, but as it progressed it got more involved. I noted the air conditioning belt was extremely worn – despite the fact that the airplane had undergone a 100-hour inspection recently – and needed to remove the upper cowling to get at the belt. I decided to remove it to prevent it from breaking during the flight, and it was worn to the point that it broke as soon as I grasped it. I didnt consider this a problem, as we have removed it during the winter for years to prevent belt wear during those months when we wouldnt need cooling.

While the cowling was off, I discovered evidence of a bird nest in progress. That took some time to clean out, and by the time the cowling was back on I discovered Id spent an hour and a half on my preflight. But the airplane looked good to go.

Although I am not an aircraft mechanic, I have worked with several over the years, assisting them with maintenance tasks on the four aircraft I have owned over the past 35 years. After 17 years and 3,100 hours in type, Im intimately familiar with the airplanes need for maintenance and how to spot problems.

The airplane was fueled with about 100 gallons and the load that day would include myself, my wife and three children. My son is also a pilot and was flying up front with me. The first leg would go from Gore Bay, Ontario, to Regina, Saskatchewan, a distance of about 922 miles. The next planned leg was from Regina to Ponoka, Alberta.

After a normal start, we were induced to hold on the ground about 20 minutes to get our IFR clearance because an inbound IFR aircraft had not canceled its IFR flight plan. Finally, at 12:27 local time we took off from runway 29.

We were cleared to climb to our planned cruising altitude of FL200 and were passing through about 10,300 feet when Toronto Center told us to maintain 12,000 feet due to traffic overtaking us.

We were approximately 40 miles west of our departure point when we leveled off and set 65 percent power for level cruise. At that moment the engine began to run rough and the power continued to decline. The manifold pressure gauge and tachometer readings decreased dramatically.

We conducted the standard loss of power checklist – switching tanks, enrichen mixture, activate boost pump, adjust throttle and check mags – but there was no improvement. We trimmed to best glide speed of 90 knots and assessed our options.

Our departure point was about 30 miles east-southeast of us. There was another airport about 22 miles west and a third about 21 miles northwest. With winds out of the west at 15 to 20 knots, we were smack-dab in the center of a triangle of airports from a glide range standpoint.

We turned back toward Gore Bay and declared an emergency due to the engine failure. There was a broken layer of strato-cumulus below us, but the ceilings underneath the clouds were high enough that I wasnt worried about the forced landing just yet.

Toronto Center cleared us to Gore Bay for an approach and asked if we wanted them to alert the emergency equipment. I told them to have help standing by at the airport, and if we couldnt make it that far Id let them know.

Selecting a Spot

If, at some point after the emergency began, the engine had been developing any power, it was clear that was no longer the case. The engine was dead. The prop was still wind-milling, but the oil pressure had dropped to zero and pulling the prop control back had no effect. We were descending at a rate of 700 to 800 feet per minute. I turned off non-essential electrical equipment in order to save the battery for the extension of landing gear and flaps.

My 21-year-old son, Ben, a graduate of the Malibu initial training course, was charged with holding the airspeed at 90 knots and keeping us on a direct course to CYZE. I briefed my wife, daughter Ginette and son Wesley on the operation of the emergency exit door and advised them to use it if the main cabin door couldnt be opened after the aircraft stopped moving. They already knew how to operate the main cabin door. They stowed the table and various loose items, and maintained quietness and calm.

The broken layer of clouds had become solid as we descended toward it. The engine seized and the propeller stopped turning, eliminating the drag of the wind-milling propeller and granting me a small measure of relief.

I calculated how much time we had aloft, based on our descent rate, which had dropped to 600 to 700 fpm when the prop stopped. I compared it with the GPS readouts of distance and time to the airport. It would be very close, but I concluded we might be able to make the field, but the urgency of the situation made even simple calculations such as these somewhat slow and difficult.

Toronto Center advised us to switch to the London FSS frequency, as we would soon be below Centers radar and radio coverage in that area. I called London FSS on 126.7 and again declared a Mayday. We entered the cloud layer and transitioned to instruments. The attitude indicator began to tumble due to the loss of the engine-driven vacuum pump, and I covered it so we wouldnt follow the instrument as it tumbled. We stayed straight and maintained wings level, on course toward CYZE during the descent through the clouds. What we saw when we broke out was disheartening.

We came out of the base of the clouds at about 3,200 feet msl, which was 2,600 feet agl in that area. I did another calculation that revealed that the airport would not be within our gliding range after all. We spotted the airport, about 10 miles away, and it was clear we would not make it. Between us and the airport was a large body of water, Bayfield Sound, and the rocky shore of Barrie Island.

We turned south, away from the course that would have taken us toward the runway, and visually searched the heavily wooded land below and ahead for an acceptable landing site. There was one area with a narrow, paved road alongside some fields that had irrigation ditches, trees, fences and buildings in them. The fields ended abruptly at an embankment, a perpendicular road, power lines and solid bush land.

Due to the recent heavy rain, I thought the surface of the field would be soft enough to cause the aircraft to flip over at touchdown. And if the airplane didnt flip, there were enough obstructions in the field to have me worried about striking a fence, building, trees or the embankment. That left the road.

Impact

I arrived at the road at about 900 feet agl. I called for 10 degrees of flaps, which Ben deployed, and made a 360-degree right turn to lose altitude. I lined up with the road while Ben called out airspeed so I could keep my head outside the cockpit. I called for Ben to extend the landing gear, which he did, then full flaps.

The road has a power line near the east side of the road, as well as trees on both sides. I stayed slightly west of the centerline of the road, realizing that I was risking contact with the trees along the west side. When we descended to approximately 30 feet above the road, Ben said that the power line was about eight to 10 feet off our left wing tip. I chose not to decrease that margin because the tree-trunks to the right were smaller than the power poles to the left, and I was anxious to avoid contact with electric wires and their associated dangers of electrocution and aircraft fire.

We were slowing from our 90 knot glide speed to our 60 knot touchdown speed when the tip of the right wing hit the top of a single tree, severing the outer 12 inches of the wing. There was a gap of about 1,000 feet in which we continued to descend under full control, then the right wing sliced the top seven feet off of three cedar trees that made contact with the wing about five feet from the wingtip. We glided another 300 feet to a large grove of cedar trees along the west side of the road.

The trees struck the same location on the wing, resulting in two severed trees and deformation of the wing structure aft to the main spar. The remainder of the trees then absorbed sufficient force to shear the entire right wing off the aircraft at the fuselage. The wing fell to the road, upside down, and spilled its fuel there.

The aircraft descended the final 10 feet to the ground and soon the left main landing gear was rolling on the road between the centerline and the west edge, and the nose gear was rolling and skidding on the west shoulder of the road. Soon the nose gear buckled under and the propeller, cowling and right side of the fuselage settled to the ground.

The aircraft continued about 50 feet in this manner, with the fuselage skidding along the sod surface of the ditch and the left landing gear rolling along on the road. The aircraft continued to decelerate, then the nose dug into some rising ground and struck a tree stump, causing the aircraft to flip tail over nose and come to a halt inverted.

Coming to Rest

The impacts absorbed the aircrafts momentum but preserved the pressure vessel almost intact. No aircraft windows were broken and no seats broke free from the railing/attachment. When the aircraft came to rest all the windows were obscured by dirt and vegetation, so the interior was dark. My daughter was able to find the main cabin door handle and was opening it at the same time as a nearby resident was opening it from the outside. He had arrived at the scene almost the instant the crash ended.

The upper half of the main door fell open, which allowed light into the cabin. I yelled for everyone to get out as quickly as possible. Everyone was hanging upside down from the seatbelts, but released them without difficulty. I had made a major oversight during the descent by not verifying that the cargo net had been secured between the aft baggage compartment and the cabin. Articles from the rear baggage compartment and from within latched cabinets had hurtled through the cabin. Unfortunately, this included several glass bottles of maple syrup, which had been in boxes at the bottom of the rear baggage compartment.

The bottles shattered against one another and against the instrument panel, creating a swath of glass shards throughout the airplane. My wife and daughter were struck by flying glass, but my son in the back was not. My son who was sitting up front with me received some cuts while crawling out of the airplane and cut his shins on the bottom of the instrument panel. He also bruised his forehead on the glareshield and bruised his chest on the yoke. I suffered cuts on my shin from the instrument panel and cuts on my arm and forehead. My teeth were loosened by the glareshield and I got a chest bruise from the yoke as well. Everyone suffered soreness of the back, shoulders, chest and neck muscles.

We all got out of the airplane and moved away from it in case of a fire. The fuel line from the left wing was damaged in the crash, allowing fuel to begin pouring into the cabin shortly after we exited. My son showed a fireman the battery location so he could cut the cable at the battery, to eliminate the possibility of electricity flowing to the aircraft electrical system. There was no fire.

Epilogue

After treatment and release from the Mindemoya hospital, some of us returned to the crash site and took measurements the next day. The distance from the power poles on the east side of the road to the tree trunks on the west side in the area where we first descended to tree height is 48 feet.

Tree branches and power pole guy wires reduce that distance to approximately 34 feet where the aircraft came to rest. The Piper Malibu wingspan is 43 feet.

If we had landed on the field just west of the narrow road, we would have touched down about 200 feet north of a cedar rail fence with some trees in the fence line. If the aircraft hadnt mired its landing gear in the soft ground and flipped over by then, it would have crashed directly into the fence and trees.

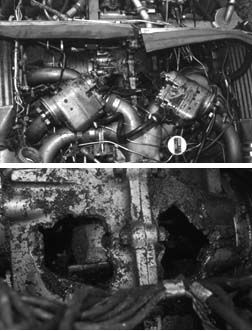

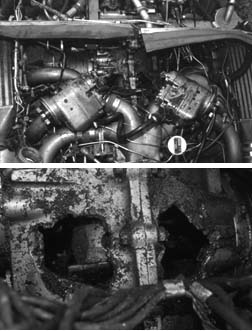

Our inspection of the aircraft engine revealed two holes in the top of the crankcase, each about four inches in diameter, adjacent to where the two halves of the case join together, in line with the two rear cylinders. It appears that one or two connecting rods separated and smashed the holes in the crankcase.

It also appears that both of the magnetos were smashed off their mountings, as both were hanging loose, suspended by the spark plug leads. The magnetos were originally mounted directly above where the two holes were created.

Most of the contents of the aircraft were soaked in maple syrup, aviation gasoline and fire suppression foam in water. The police prevented us from removing luggage and personal effects from the aircraft until it had been moved from the crash site to Gore Bay Airport the day after the accident.

We obtained transportation from Gore Bay to Toronto aboard the corporate aircraft owned and operated by Manitoulin Transport, then from Toronto to Alberta aboard a WestJet flight.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Aftermath.”

-Perry Wilson has owned his Malibu for 17 years. His flight experience includes 3,100 hours in the Malibu and nearly 3,000 hours in other retractable gear airplanes.