Every now and then, I come across an NTSB accident report that leaves me shaking my head. After absorbing the facts and the outcome, I want to reach out to grab the pilot and shake him—it’s always a “him”—into some more enlightened state of awareness regarding the possible consequences of his actions. So it is with this month’s Accident Probe entry, which pretty much represents the gold standard of what not to do when it comes to aircraft ownership and operation. Rather than attempt to explain the inexplicable as an introduction, let’s just dive right in.

BACKGROUND

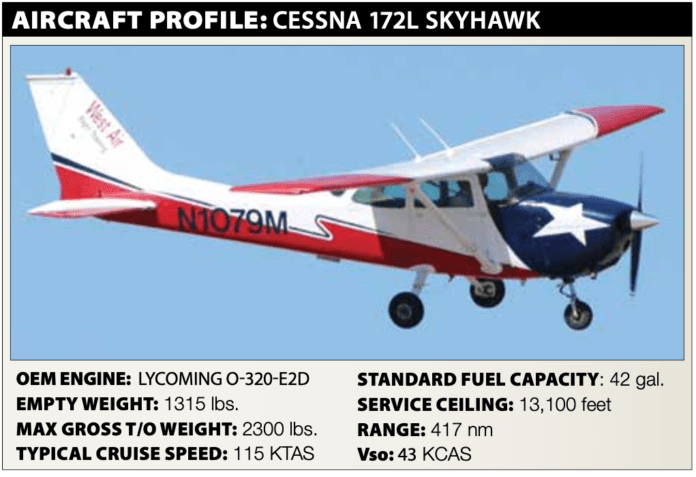

On August 16, 2018, at about 1935 Central time, a Cessna 172L Skyhawk impacted trees and terrain shortly after takeoff from the turf runway at the Rhome Meadows Airport (T76), Rhome, Texas. The commercial pilot was fatally injured; the three passengers sustained serious injuries. The airplane was substantially damaged. Visual conditions prevailed.

A family member later stated the pilot retrieved the airplane from under the open-air shelter for “family fun night” and was giving rides to family members. The pilot had flown the airplane about a week before, then twice again immediately preceding the accident flight. There were no reported anomalies with the airplane.

A pilot-rated witness saw the airplane land and taxi back. Three passengers boarded while the engine remained running. The airplane began its takeoff roll but did not sound like it was developing full power, and the takeoff roll was longer than expected. Becoming airborne, the airplane’s nose pitched up “very high” as it climbed to about 50 feet agl, and then the nose came back down. The airplane flew down the runway, appearing to accelerate, and then pitched up and climbed to about 300 feet agl. It then made a left turn and descended out of view, coming to rest inverted about 350 yards north of the departure end of Runway 13.

INVESTIGATION

Postaccident examination revealed all flight control cables were con- tinuous from their respective control surfaces to the cockpit controls. The flaps were retracted. The fuel selector handle and valve had been moved to the OFF position by first responders. A small amount of fuel was found in the firewall fuel strainer. Both wing-mounted fuel tanks were impact-damaged, but about two gallons of fuel were drained from them during the recovery process.

According to the NTSB, “Two empty beer cans were found in the front left floorboard area near the rudder pedals. A rodent’s nest was found inside the left wing…. A significant amount of cobwebs were observed in the engine compartment. The airbox was clear of obstructions. A large mud dauber nest was found on the fins of the oil cooler. The ELT was found in place with battery acid residue on the outside of the case. An automotive battery was installed in the airplane.”

The propeller blades were straight and relatively undamaged, indicating the engine was not producing power at the time of impact. Organic debris similar to insect cocoons was found in the fuel strainer, which was mostly full of a liquid consistent with 100LL. The fuel tested negative for water.

“The main fuel line from the gascolator to the carburetor was a hydraulic hose manufactured in July 2013,” the NTSB noted. The exhaust system’s flame cones were either deteriorated or missing altogether. The left magneto’s ignition timing was verified at 25 degrees before top dead center; the right magneto’s timing was about 30 degrees BTDC. Both magnetos generated spark when turned. There was no information on the oil filter about the date or engine time when it was changed.

The pilot’s wife told investigators that the airplane’s maintenance logbooks were never received from the previous owner after the airplane was purchased in 2013. According to the NTSB, “There was no documentation of maintenance performed since that time and no evidence that the airplane had received an annual inspection. A representative for the previous owner could not find the logbooks.”

On October 13, 2017, the date of his most recent medical certificate application, the pilot reported 8000 hours of flight experience and 125 hours in the preceding six months. “The pilot’s wife stated that he did not log his recent flight time and had not recorded flights in his pilot logbook since the 1990s,” the NTSB said.

Toxicology testing identified ethanol in the pilot’s tissue samples at levels greater than can be explained by postmortem microbial activity and in excess of FAA regulations. Active and inactive metabolites of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive substance in marijuana, were detected in the pilot’s urine. It’s important to note that there is no established relationship between THC levels and impairment, according to a 2017 Report to Congress by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, an FAA sister agency.

During the accident flight, the pilot was seated in the front right seat with a minor in the front left seat; an adult and minor were seated on the rear bench seat.

PROBABLE CAUSE

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s inadequate maintenance of the airplane, which resulted in a total loss of engine power due to fuel starvation when organic debris restricted available fuel to the carburetor, and the pilot’s impairment due to the ingestion of alcohol, which affected his ability to safely operate the airplane following the loss of engine power.”

According to the NTSB, “It is likely that the fuel line was removed for an extended period of time and eventually replaced with the automotive hydraulic hose, during which time the fuel system was exposed, which allowed insects to nest inside; because there were no maintenance records associated with the airplane, it could not be determined when the hose was replaced. During the accident flight, it is likely that the organic material became dislodged and restricted fuel to the carburetor, which subsequently starved the engine of available fuel and resulted in a total loss of engine power.”

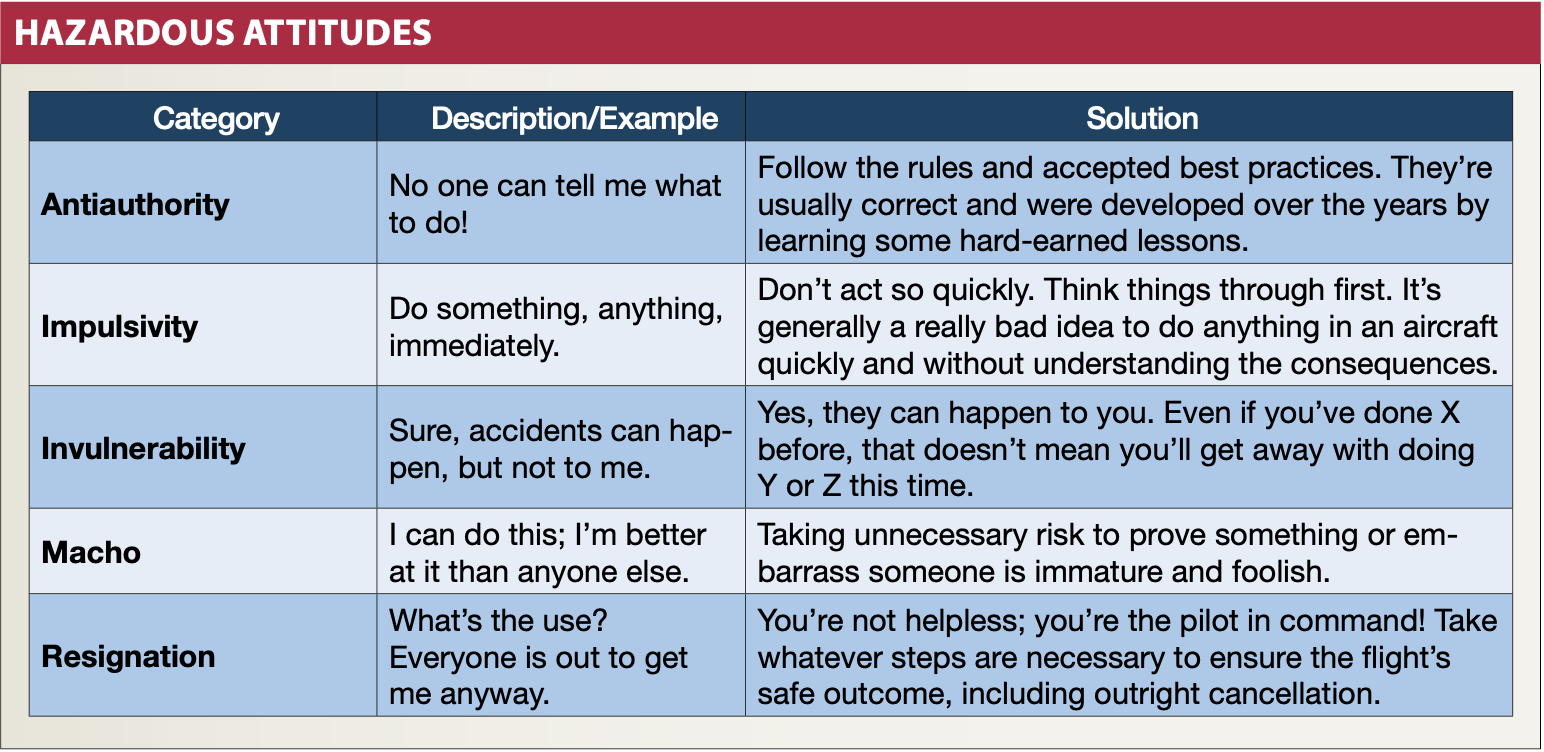

We all know at least one pilot who occasionally displays one or two of the hazardous attitudes the FAA identifies (see the sidebar on the opposite page), but it’s difficult to find one who checks almost all the boxes. Now you have.