Commercial air travel is by far the safest mode of modern transportation. General aviation, however, is not as safe. Many factors have improved both categories’ safety records over the years, but procedures and policies established by regulators/industry and implemented by commercial operators have been wildly succesful. These policies and procedures have been introduced over the years due to accidents and incidents that have occurred.

While not all policies and procedures established by commercial operators can be followed by GA pilots, many can be, or they can be modified to fit the aircraft, crew and operation in general. Slight changes to your particular operation to parallel air carrier procedures, policies and techniques may seem trivial but, over time, can enhance safety and reduce the overall risk of accidents.

BACKGROUND

In the early days of aviation, accidents were much more frequent and tended to be more spectacular with widespread publicity. Aircraft and engines were generally unreliable, pilots took unnecessary risks and instruments/navigation aids were poor by today’s standards. Training for pilots and mechanics was haphazard and the government provided little to no supervision of aviation in general. It was a time of learning and making improvements as well as setting standards, procedures and policies that built on preventing recurrences of previous accidents.

Military operations, especially during and after World War II, saw a huge and positive impact on aviation safety and set the standards for the future of aviation laws350 and procedures. But there remains a large gap in accident rates between general and personal aviation, and commercial operators. A significant portion of the divergence between the two groups can be attributed to not following recommended policies and procedures.

With this in mind, let’s run through an overview of the kinds of policies and procedures commercial operators are required to adopt and implement, with an eye toward adapting them to our own, owner-flown operations. (Hint: Not all of them lend themselves to easy or inexpensive adoption.)

If you accept the premise that professionalism is a state of mind and not dependent on the source of one’s paycheck, we all can fly our aircraft professionally. Some consistency and discipline is required, however, and that may be too much for some. Consider how we might be tempted to cut corners in these areas:

Personal Minimums?

While personal minimums can be a part of your pro-pilot aspirations, the problem arises when you’re inevitably tempted to break them. If your takeoff minimums are 3000 and five, what will you do when it’s 2500 broken but with 10 miles of visibility?

Aircraft Maintenance

“It flew in, it must be okay to fly out” is not a preflight inspection, nor is it a maintenance policy designed for efficiency and longevity. Quality maintenance is expensive—we get it—and not even the airlines get it right all the time. But there needs to be some discipline.

Planning/Dispatch

Too often, pilots think of “how to get there” when they really should wonder “whether” they need to get there at all. Having a well-equipped dispatch office allows a scapegoat when we want to cancel for weather. When we don’t have someone else to blame, external pressures can result in taking a trip we don’t want to fly for the wrong reasons.

Postflight Inspection

How many of us do any kind of detailed post-flight inspection other than “the big parts are still attached”? Did you verify the fuel aboard, that all the exterior lights still work and there are no slack tires? Do you know the time remaining before required inspections or the next oil change? — J.B.

STANDARDIZATION

For example, new hires at a commercial operator must complete an FAA-approved training program. Among items covered are operating specifications and a general operation manual or its equivalent. These manuals spell out the policies and procedures of the company and are very important for a crewmember to know. The ops specs are a contract of sorts between the operator and the FAA, with specifications tailored to the operation.

The specs can be more restrictive than the FARs, but not less restrictive. Content of the specifications includes items such as approved aircraft, management personnel, required navigation equipment, operational control, electronic flight bag authorization, weight and balance program, conducting operations in oceanic or foreign airspace, plus crewmember flight/duty times. Also included are approved airports for primary, alternate or emergency operations.

This list is not exhaustive and, as you can see, there is a lot of familiarization and memory required. A general operation manual (GOM) is prepared using the appropriate FARs as guidelines. The purpose is to provide those personnel engaged in flight operations with company procedures and policies and to assist in the proper discharge of their duties.

Can an operations manual be developed and adopted by a Part 91 operator? Sure; corporate FAR Part 91 flight departments do it all the time, and not just to ensure their upper-management passengers are pampered. Don’t expect (or even ask, for that matter) the FAA to bless your FAR 91 ops manual, however, since there’s no regulatory framework providing guidelines or approvals. You can develop your own, however. The trick is enforcing it, which we’ll get to soon.

PLANNNG/DISPATCH

Commercial operators must utilize dispatch or some type of flight following, depending on the type of operation, and provide the pilot in command with a flight plan and dispatch release. The captain and dispatcher must agree on the planned flight and the captain’s signature is his/her acceptance of the plan. Dispatch will plan a flight using all information that could affect the flight, with weather conditions being just one aspect of the planning. Notams, aircraft performance, airport/runway analysis, weight and balance, fuel requirements, alternate airport, en route delays, severe or dangerous weather such as thunderstorms or volcanic activity are all taken into consideration.

Additionally, departure and arrival procedures, temporary flight restrictions and all FARs pertaining to not only the flight but the crew and the aircraft as well are incorporated. Minimum equipment lists (MELs) are also verified, as inoperative items may not allow a Category II approach, for example, or result in an altitude restriction. Comprehensive flight planning is heavily relied upon by commercial flight crews and greatly enhances safety.

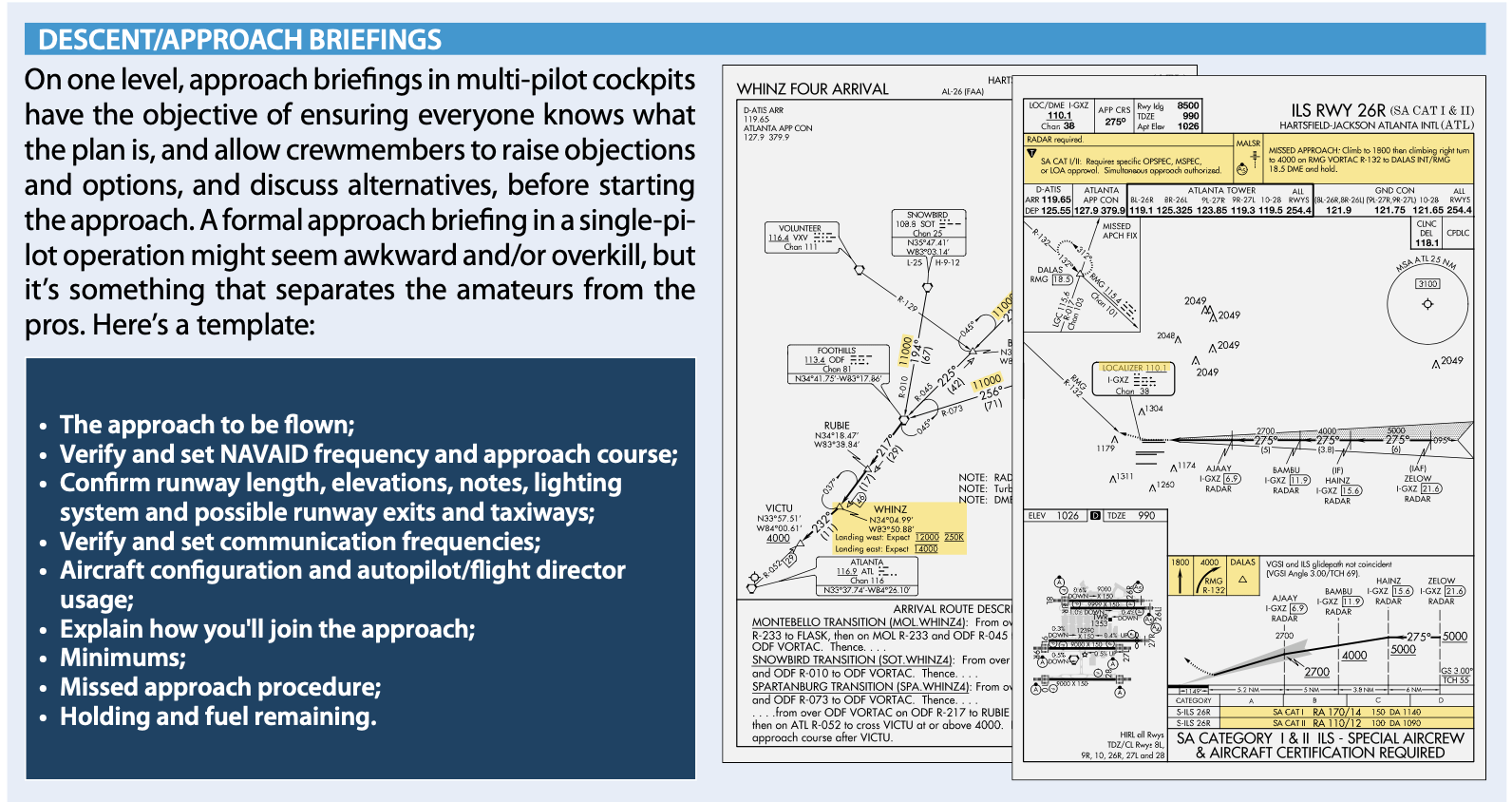

These are just some of the tasks a pilot must perform before engine start, and how being a crewmember aboard a commercial operation can both reduce and increase workload. Of course, planning, coordination and standardization doesn’t end at the ramp. The sidebars at left and on the opposite page offer some suggestions on how single- or multi-pilot GA operations can adopt some of the standard procedures present in professional/commercial cockpits.

Another operational difference between most GA flights and commercial ones is cockpit verbalization, especially when single-pilot. With multi-pilot crews, communication between the people in the front office is crucial to ensuring the airplane is where it should be and headed where everyone wants it to be next. When two pilots are in a typical GA cockpit, verbalization is rarely standardized. Examples of callouts GA pilots may wish to adopt as a means of increasing their professionalism—and perhaps helping prepare them for a cockpit job—can include:

Takeoff: Airspeed alive; 80 knots; V1; VR; V2, as required.

Configuration: Positive climb rate, landing gear up; Flaps to intermediate position or retracted.

Top Of Climb: 500 feet below target altitude; Level off; Set power/mixture; Cowl flaps as required; Pitch trim set.

Top Of Descent: Power as required; Target altitude; 500 feet above target altitude; Level off; Power as required.

Approach/Landing: 1000/500 feet to go when approaching intercept altitude; Final approach fix; Localizer alive; Glideslope alive; Autopilot capture; One-dot deviations; Approaching minimums; At minimums; Runway in sight/not in sight; Go-around/Missed approach.

WHAT WOULD A PRO DO?

Should a discrepancy be discovered at any time during these processes, it must be addressed in some way, such as having corrective action taken or deferral according to minimum equipment list procedure. Maybe a re-route around storms is in order, or a change in cruising altitude to remain out of icing conditions. In general aviation, there’s often no one to bounce these questions off. For example, should I add a quart of oil, since this might be a long flight? Or, how will the taxiway closure at my destination airport affect my landing and roll-out? When will a combination of headwinds and tight reserves mandate a fuel stop?

These are typical questions a single GA pilot must confront on a regular basis, and there’s often no trained, responsible person available to act as a sounding board. But the ways in which we respond to these challenges help define the professionalism with which we approach the flight. Based on what we know about the operating rules found in FAR Parts 121 and 135, we can make informed choices if we ask ourselves how a professional crew might respond to them.

For example, with so many other elements of a commercial flight supporting its safe and efficient completion—the maintenance department, the dispatch office, the ops specs and standardization training—how would an airline decide the issue confronting you?

It can be as simple as making related decisions to err on the side of caution. Or, if you’re somewhat cynical, how would maintenance cover their butts when a discrepancy is found during the preflight inspection? What would dispatch say about fuel margins to cover their butts when a deviation around weather is needed?

TRAINING

Another area that doesn’t get the attention it deserves when contrasting typical GA operations with their commercial counterparts is training. A FAR Part 121 crewmember typically undergoes some type of training every six months. When was the last time you rode with an instructor? When was the last time someone quizzed you on your aircraft’s limitations? When was the last time you shot an Instrument Landing System to minimums in your twin with one engine inoperative?

How often you fly and how often you train obviously affects how you perform in the cockpit. For example, even though pilots returning from furlough during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 met all the training and recent-experience requirements, they often remarked on how rusty they had become, according to sources like ASRS reports.

Non-commercial pilots, meanwhile, often merely meet the minimum standards when it comes to training—and it’s important to understand that a flight review isn’t designed to be recurrent training. Instead, “it is a proficiency-based exercise in which the airman is required to demonstrate the safe exercise of the privileges of his or her pilot certificate,” according to the FAA. Paradoxically, the need for regular training is greater the more often we fly. Maintaining instrument currency comes to mind, as does performing emergency maneuvers. The object is not only to ensure we are proficient at these tasks but also that we perform them the same way each time. Which brings us back full circle to one of the central features of professional crews: standardization.

CONCLUSION

While many policies and procedures for commercial operators may not be appropriate for general aviation operators, many can be adopted or modified for use even with the most basic aircraft. For example, consider the takeoff briefing. Do you brief yourself on what to do in the case of an engine failure? Turn back or land straight ahead? The answer likely will depend on conditions, the airplane, when and where the engine quits and whether you’ve practiced the maneuver. At what point could you reject a takeoff and stop on the available runway? Are you familiar with audio and visual warnings for the aircraft you fly, and what should be immediate action items for abnormals?

Policies and procedures, checklists and flight manuals have all evolved over the years due to accidents. Do your part for safety and give these items some consideration so as to reduce the risk of an accident.

Mike Berry is a 17,000-hour airline transport pilot, is type-rated in the B727 and B757, and holds an A&P ticket with inspection authorization.