When I was in the Air Force, my colleagues would tell the story of how some fighter pilots used to do touch-and-goes on a tall, flat mesa that stuck up somewhere in the southwest desert, perhaps in Nevada or Arizona. It was dubbed “Touch-And-Go Mesa.” (Imaginative, huh?) One pilot supposedly did the thing, and then bragged about it and told others. Then another pilot did it. And another. Soon it was a regular thing because word got around, the fighter jocks talking to each other, saying, “I heard this is fun to do.”

According to legend, the rancher who owned the land (and the mesa) got tired of the pilots doing touch-and-goes on top of his mesa and decided to do something about it. The story is that he put some obstacles on top of the mesa. The next pilot who tried to do a touch-and-go on Touch-And-Go Mesa tore off his landing gear and, somewhere on top of a mesa in the southwest desert is a set of fighter-jet landing gear. So goes the tale.

WHAT ABOUT THE PILOTS?

Every time someone told this story, another pilot would ask, “What happened to the guy?” As in, “Did he get in trouble?” Not, “Did he have to eject?” or, “Did he land gear-up?” or, “Was he hurt?” Nope, none of those. It was always “What did Dad say?” Dad being some stern-faced colonel, or at least a major. That story might not be true. I personally never climbed the mesa, or heard details that would verify the story, like which base the jet was from, what kind of jet it was, etc.

But these two things are true: Pilots tell each other stories that other pilots listen to and believe, and then go out and do what they heard was “cool.” Also, when a pilot screws up and has a mishap, many other pilots ask, “What happened to the pilots? Are they back flying?” And they’re not talking about being injured or dead, they’re asking, “Did the pilot get in trouble and get grounded?”

Some pilots reading this may scoff at such nonsense, and deny these two things. Of course, these pilots are mature, God-fearing, family folk. They probably floss every day. They really do care what happened to the pilot—is the pilot okay? Were they injured? Did they get remedial training?

This article is not about or for those pilots. Instead, it’s for people like, uh, me, who have listened to stories other pilots told, and went and did the same thing and scared the heck out of themselves. It’s also for those who say to themselves, “I wonder if that pilot is still flying, or did they get their license yanked by the FAA?”

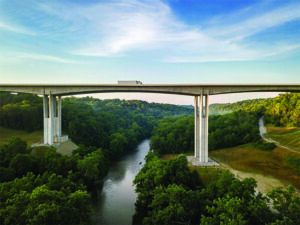

According to online sister publication AVweb.com, Martha Lunken flew her Cessna 180 under the Jeremiah Morrow Bridge outside Oregonia, Ohio, in March 2020. She then checked in with ATC and was told her transponder was off. She reset it with a new code and it resumed working.

Subsequently, FAA officials said that she’d shut it off on purpose to stop the system from tracking her while she flew under the bridge. “The agency used a new section of its Legal Enforcement Actions guidebook for FAA staff, which calls for revocation of a certificate for ‘operating an aircraft without activated transponder or ADS-B Out transmission (except as provided in 14 C.F.R. § 91.225(f)) for purposes of evading detection,’” AVweb wrote. Lunken received an emergency revocation letter on March 19, 2021. — J.B.

ONE EXAMPLE

Two USAF T-38 pilots once canceled their IFR flight plan about 12 miles out of their destination somewhere in the southeast U.S., and went VFR into the airport and landed. Why? Other pilots told them it’s fun to “cancel IFR and drop in.” But oops—it was the wrong airport, one aligned with the one they were supposed to land at, but about 10 miles closer. The runway was almost too short to get stopped on, and they burned out the brakes and blew the tires while skidding to the end of the runway. This happened to pilots at my base.

Every single time I heard (or told) the story, other pilots asked, “What happened to those pilots?” Yup—pilots (like me) wanted to know if they “got in trouble.” They didn’t, by the way. In fact, one of them got promoted to a good job in the check section. (I knew you wanted to know.). He’s probably flying for a major airline now as his punishment.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there isn’t much FAA reference material on what some might call “buzzing” a location with an airplane. By which we mean low-level maneuvering near some ground feature. Warnings against buzzing are part of safety briefings from the FAA and other sources on avoiding controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) and/or loss of control in-flight (LOC-I), and in discussions of situational awareness, of course.

Yes, there are regulations. The primary one is FAR 91.119, Minimum Safe Altitudes. Unless we’re flying a helicopter, powered parachute or weight-shift-control aircraft, the FAR says the minimum altitude is 500 feet above the surface, except over open water or sparsely populated areas. In those cases, the aircraft may not be operated closer than 500 feet to any person, vessel, vehicle or structure. Congested areas deserve greater protection, and the minimum altitude is 1000 feet above the highest obstacle within a horizontal radius of 2000 feet of the aircraft. Legend has it the FAA considers two or more people to comprise a congested area. It’s also open to interpretation what a sparsely populated area is.

It’s also unsurprising there’s not some sort of checklist or best-practices statement about buzzing. We’re not going to offer one, either. But if you absolutely, positively have to go out and buzz something or someone, we suggest the items at right, at a bare minimum. —J.B.

Before You Buzz

- Set a hard “deck,” complying with the FARs, below which you will not descend.

- At altitude, survey the area and the chart for obstructions, with attention to approach/departure paths.

- Your airplane’s weight-adjusted maneuvering speed, VA, should be used as your maximum.

- Do not make any abrupt control inputs.

- Remember: a high-speed trajectory is harder to alter than a slower one, due to inertia.

EXCEPTION TO THE RULE?

How about Martha Lunken, the pilot with about 14,000 hours of flight time who flew under a bridge back in 2020? That pilot—most likely, it would have been a man but it was a woman this time—got in trouble, as many of us may recall. But before she got spanked by the FAA, she told her story to lots of pilots.

Perhaps some pilots might ask, “How close was the pilot to people on the ground under the bridge,” or, “How close did the aircraft come to the bridge?” or, “Was anyone in danger?” etc. I put forth this idea: most pilots ask, “How did the pilot get caught? What happened to the pilot? Did that pilot lose their license?”

How many pilots heard her tell her under-bridge-flying story and thought, “That sounds cool!”? Answer? Lots of pilots. Right up until she got caught and hammered by the FAA. Turns out she probably had done it before, since she took “the fifth” on a YouTube video when asked. The sidebar above has more details on this episode.

BACK IN THE OLD DAYS…

Which reminds me of the “canyon runs” we used to do in the T-38 many years ago. And let me just say here that any statute of limitations must be over by now. I hope.

No, not the Grand Canyon. That canyon, thanks to the two dudes from Beale Air Force Base who flew below the rim, was off-limits. Two pilots in a T-38 in the 1980s got nailed for flying below the rim. They went head-to-head with a sightseeing airplane and nearly collided. Some people who saw the ‘38 jocks—especially the pilots flying the sightseeing airplane they almost hit—called the Pentagon that day. This is before the Internet, cell phones, etc.—people just called the Pentagon, because “that’s where the military is,” I guess they figured. Apparently the Pentagon has a complaint line of sorts. I can just hear it:

Pentagon: “Hello, this is the Pentagon Complaint Hot Line. How may I help you today?”

Caller: “Some pointy-looking white jet just went whipping right by the window here, at eye level!”

Pentagon: “Ma’am, please stay calm, and tell me your location.”

Caller: “Why, I’m at, let’s see, table #3 at the Canyon Coffee House, in Grand Canyon Village. Would you like to know what I ordered for breakfast, too?”

Pentagon: “Ma’am, ma’am, I don’t need the attitude, just tell me what you saw.” Etc.

The Pentagon called the U.S. Air Force. The Air Force asked itself, “Let’s see, how many white, fast-moving jets are airborne in Arizona near the Grand Canyon right now? Aha! One.” And it was those guys, who then got spanked upon landing and a “new rule” was made: No one in the military flies lower than 10,000 feet above the “big ditch.”

Our canyon in Texas, not the Colorado River one but a Rio Grande River canyon, was a little secret, passed on from one instructor pilot (IP) to another. It usually went something like this (IP speaking in a low voice or whisper): “Hey—have you ever done a ‘canyon run’ before?”

So off a new guy (like me) would go—two instructors in a T-38—to drop below the two rocky rims of a mini-Grand Canyon on a winding river in the middle of nowhere, at 450 knots. We’d blast along a couple hundred feet above the river, following the contour of the river, staying away from the rock walls, turning left and right. And I mean turning. At the end of the canyon run was a sheer vertical rock wall, maybe 100-200 feet high—the river disappeared around a sharp corner. You’d yank the T-38 nose straight up, pop up, clear the wall, roll inverted at a 1000 feet agl or so and pull, and roll out wings level.

Why did I do this? Because someone told me it was fun. And they were right.

I think if any pilot ever had trouble out there and had to bail out, or if they crashed, the first question we T-38 IPs would have asked would have been, “What happened to them—did they get in trouble? Are they back on flying status?”

I know, I know; you’re asking, “Where is that canyon?” I’m not telling. While what we did was legal, it wasn’t smart. There isn’t a statute of limitations on stupid.

Plus, I bet the T-38 IPs at Laughlin Air Force Base, near Del Rio, Texas, are still “doing canyon runs” on the Rio Grande River in Big Bend National Park, located at N 29.07, W 103.40. Wait a minute, did I just…?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there isn’t much FAA reference material on what some might call “buzzing” a location with an airplane. By which we mean low-level maneuvering near some ground feature. Warnings against buzzing are part of safety briefings from the FAA and other sources on avoiding controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) and/or loss of control in-flight (LOC-I), and in discussions of situational awareness, of course.

Yes, there are regulations. The primary one is FAR 91.119, Minimum Safe Altitudes. Unless we’re flying a helicopter, powered parachute or weight-shift-control aircraft, the FAR says the minimum altitude is 500 feet above the surface, except over open water or sparsely populated areas. In those cases, the aircraft may not be operated closer than 500 feet to any person, vessel, vehicle or structure. Congested areas deserve greater protection, and the minimum altitude is 1000 feet above the highest obstacle within a horizontal radius of 2000 feet of the aircraft. Legend has it the FAA considers two or more people to comprise a congested area. It’s also open to interpretation what a sparsely populated area is.

It’s also unsurprising there’s not some sort of checklist or best-practices statement about buzzing. We’re not going to offer one, either. But if you absolutely, positively have to go out and buzz something or someone, we suggest the items at right, at a bare minimum. —J.B.

Before You Buzz

- Set a hard “deck,” complying with the FARs, below which you will not descend.

- At altitude, survey the area and the chart for obstructions, with attention to approach/departure paths.

- Your airplane’s weight-adjusted maneuvering speed, VA, should be used as your maximum.

- Do not make any abrupt control inputs.

- Remember: a high-speed trajectory is harder to alter than a slower one, due to inertia.

SHORT FIELD PRACTICE

Fast forward from my days in the USAF to not so long ago when I was at a flight school, telling my student about a shorter-than-average runway. An eavesdropping older pilot, a fellow CFI, says, “Oh, yeah? You should try flying into so-and-so airport—that one’s a challenge.”

I looked at that airport in the Chart Supplement, formerly known as the Airport/Facility Directory. The runway was short—1800 feet long, with lengthy displaced thresholds at both ends, so about 1500 feet of usable runway. Thirty feet wide. I thought, “He said it was cool, let’s try it.”

I flew there with the student, and holy moley, that was dumb. Not flying there with the student, but flying there, period. The Chart Supplement says you need a seven-degree glide path on one end and four degrees on the other. Why? To clear the trees. We did a touch-and-go, which was hairy—we were on the concrete for about five seconds. But I wasn’t done. Oh no, I had to go back solo a couple of days later, because I wanted to “get good at” this little airstrip. I thought, why not? My older, seasoned CFI buddy said it was “a challenge.”

I flew back there in a Cessna 172 and overflew the field for a right-turning entry to 45-to-downwind, and—I couldn’t find the doggone field! I had just flown over it, turned back toward it to enter a 45-to-downwind, and couldn’t find the field.

I looked at ForeFlight and realized I was befuddled. No, not really; I realized I was befuddled before I looked at ForeFlight. I was lost, turns out, so I did a 180-degree turn, flew away from the missing airstrip and reflew a 45-to-downwind using the Magenta Line For Idiots. That miserable little airstrip is surrounded by trees on both sides and both ends, and it’s 30 feet wide. Unless you know where it is, coming at it from an angle at 1000 feet agl, you can’t find it. I should say I couldn’t find it.

So, I learned a good trick there—have a heading picked out in my mind that is about 45 degrees to the downwind leg. The downwind leg is a 180-degree heading to the runway, and a 45-to-downwind heading is what, let’s see…trigonometry. No, it’s simple math, but best to do it in advance. So for Runway 32, the downwind heading is 140, and a 45-to-downwind is 095 degrees.

After locating the hidden field, which is as wide as someone’s driveway, I tried to do a touch-and-go in a pretty good crosswind, like 15 knots. There was no way I could get that 172 down on that little strip, with its steep glide paths. I tried three times and gave up. On the way back to my home airport, I realized that I was doing exactly what I knew I shouldn’t do. I had listened to some guy talk about how some thing was “cool” and then I tried it. It was not cool, and worse—it wasn’t even fun. It was downright dangerous.

MORAL OF THE STORY

According to the AOPA Air Safety Foundation, “[t]he chance of an angle-of-attack accident is higher during buzzing, although that type of maneuver can hardly be considered normal flight. GA pilots do not usually receive training on this type of flying.” But we do engage in it. Flying at low levels and high speeds is abnormal—most airplanes spend the vast majority of their time in straight-and-level flight, which means so do their pilots.

It’s unlikely you’ll find an instructor to teach you how to fly and maneuver at low altitudes. Unfortunately, the on-the-job training can be fatal.

Matt Johnson is former U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot and KC-135Q copilot. He’s now a Virginia-based flight instructor.