So I’m flying along, fat, dumb and happy in my Lancair IV-P. I had blasted off out of Fargo, N.D. There is good news and bad news about the frozen north, my new home. Okay, the bad news first—it’s really cold here. Did you know that the Centigrade/Celsius system is the same as the Fahrenheit measuring system in Fargo? Well, it is—at minus 40 degrees. Yep, you don’t need a “C” or an “F” at minus 40 degrees—there’s only one minus 40 for both systems. You know it when you feel it, trust me.

Leaving Fargo, I flew over to Grand Forks, N.D. (motto: “We’re like Fargo, only colder!”) and did a touch-and-go. Then I pulled into a closed pattern so I could relive my T-38 days in the U.S. Air Force, and then exited the pattern, heading to Grafton, N.D. I spent the flight fooling around with my glass cockpit (“the heads-down display”), the autopilot and the radio and thinking about how Grafton had beaten us in the North Dakota boys’ high school hockey tournament in 1979 (although I am so over that).

INTRODUCING MARTHA

All of a sudden, I’m still at about 4000 feet about zero miles from the field. Since I was lined up with the runway, which looked like a black Sharpie pen line in the snow, and since it was so far away, I lowered the gear and flaps for the 360 I had to fly to get down.

My Lancair has a distinctive paint job and an expensive panel, a major component of which is a Garmin G3X Touch flight management system. One of its cool features is a woman I’ve come to refer to as Martha who is fond of telling me whether my landing gear is up or down. (I imagine someone working in a small, windowless room in Olathe, Kan., whose full-time job is to tell me these things, and more.) But I digress.

Entering the 360 to lose some altitude at Grafton, I slap down the gear handle, expecting Martha to soon say the usual, “Gear is down, thank you!” Instead, she said, “Gear stopped!”

Just like my heart.

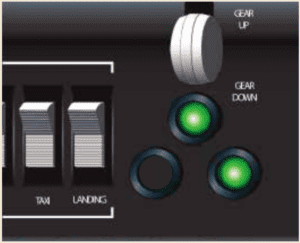

The left main gear light was not green like the nosegear light and right main light. Martha, however, was a bit behind the curve, insisting, “Put gear down now! Put gear down now!” Sensing her anger, I blurted out an expletive and stared at the two green lights. They seemed to me to be kind of cocky, like, “Hey, we’re green, we’re not the problem,” all while they glanced nervously at their unlit pal.

So I look at the fuzzy view from my handy-dandy partially oil-covered video camera mounted on the underside of the aircraft to check the gear. They all looked down, but Martha was insistent. I finally raised the gear handle and held my breath, and clunk, clunk, clunk, they all came up. Martha got off a quick, “Gear is up, thank you!”

Sweet—at least they’re up. Now then, where is Fargo again? Oh, yeah—90 miles behind me. But I have tons of gas, so off I go back to Fargo.

PHYSIOLOGIC STIRRINGS

Suddenly, I notice I really have to go to the bathroom. The body is a funny thing, and reacts to fear like that. Good thing I brought a great big metal jug with a screw-top lid on it which wasn’t full of water. Suddenly, I was also aware of where every single airport was that was sorta near me, and which roads were near me, and which ones were straight—which in North Dakota is all of them, even the gravel ones.

So I fly back to Fargo at about 7500 feet, slow down and lower the gear way north of town to check it. I’m on the Fargo Approach frequency 120.5—oops, I mean 120.4—calm down there, hot shot, I thought to myself. “Maintain aircraft control, analyze the situation, take proper action,” they drilled that into us in the Air Force. The results? Only two green lights again. As I remember it, Martha got more insistent: “Put gear down now!!” I cycled the gear again—it was no-go, still only two green. Martha had become inconsolable.

Some airplanes equipped with retractable landing gear have an emergency extension handle in the cockpit. Pulling it releases the uplocks and allows the gear to free fall or extend under their own weight. Other airplanes use a compressed gas, usually nitrogen, to release the uplocks and allow the gear to fall into place.

Mechanical systems also are used to crank the gear down into position while hydraulics, with pressure provided by an electric or manual pump also are popular.

There are two keys to using any airplane’s emergency landing gear extension system. First, and as always, fly the airplane. The cockpit exertion required by some systems may distract the pilot from this task, which includes maintaining the desired altitude and looking for traffic.

The second key is using the emergency extension checklist and following the steps it calls for. — J.B.

OVER TO TOWER

I was handed off to Fargo tower from approach control, and tried to sound cool on the radio, saying to approach, “Over to tower, thirty-three eight, four delta kilo,” and approach said, “Good day,” like some friendly ATC people do. Especially, here, some 40 miles south of the North Pole, where the ATC folks actually work in igloos, and they’re just happy to hear a pilot’s voice on their short-wave hand-crank-powered radios, huddling in parkas around a wood-burning stove.

Out West in places like Montana, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, the ATC folks can be chatty. One time an air traffic controller way out in the middle of nowhere gave me a ground speed readout, when I asked him for one. A buddy and I were flying a USAF T-38 eastbound at FL 390, flying at the usual speed of 0.9 Mach in the jet stream, and we were curious how fast we were crossing the ground since we couldn’t tell, because in 1990 the T-38 panel was pretty simple, with only “steam gauges.” The lonely controller said, “Hoo boy, Roper 35—you boys are really haulin’ the mail today! I got you at 904 miles an hour groundspeed!”

But back to the present: I’m talking to Fargo tower! I’m so close to home, with multiple plowed runways of snow and my friendly awesome mechanic! (And those good Dotz pretzels in the FBO, Fargo Jet Center.) I tell the tower my gear lights don’t indicate three green down and locked and I say I’m declaring a “precautionary landing.”

A young man’s voice asked me, “Would you like a flyby?” At first I thought he meant a chase ship, and I pictured some Air National Guard Reaper drone off my wing, but then realized he wanted to know if I wanted to “fly by” the tower for him to look at me. I said yup.

SOB

Then he asked me, “How many souls on board?” Flying is all fun and games until you hear something like that. I told him, “One,” and that I have four hours of fuel remaining. The U.S. Air Force controllers always wanted to know, “State of nature of emergency, number souls on board, and fuel remaining in minutes.” Somehow the “souls on board” radio call and the flyby request made me twitchy.

Suddenly this “two-green” deal was all very “real.” I’m flying in Class D airspace near the ground, my gear isn’t indicating “down and locked,” and there’s an airliner—I think Allegiant Air—taking off on Runway 18, which I’m going to fly perpendicularly right across so the tower can look at my gear.

After, the young tower man’s voice, now sounding about 15 years old, said, “They all appear to be down. Would you like us to roll the trucks?” I key the mic to talk, but can barely eke out a call. I said, “Sure, you can roll the trucks,” and realized I had almost no saliva in my mouth.

Meanwhile, Martha’s voice was fine, and she kept yelping, “Put gear down now! Put gear down now!” until I pulled the “gear-minder” circuit breaker. (Sorry, Martha, catch ya later. I’ll give you a good Yelp.) And to think I paid good money to listen to her.

Matt was lucky his left main landing gear didn’t fold up on the runway after landing. Other scenarios aren’t as rosy, especially when it comes to one main leg is down and the other isn’t. In that case, retracting the gear fully and landing on the belly may be the best option.

In our March 2023 issue, Tom Turner covered intentional gear-up landings, when the gear won’t come down no matter what you do. One of the biggest takeaways from that article—there are several—is to use the manufacturer’s checklist and to prepare the cabin for immediate egress when the airplane comes to a stop. — J.B.

PROCEDURES

Oh, I forgot to mention…since I did not trust my somewhat fuzzy-looking belly-mounted video camera or the tower’s “all three down” call, I did the emergency gear lowering procedure: slow below 120 KIAS, pull the hydraulic pump’s circuit breaker, put the gear handle down, and then use the massive floor-mounted gear pump to “pump until stiff.”

Well, I pumped fanatically on that handle, like a 1930s North Dakota farm boy trying to get water from a well, until it was by golly stiff, and I couldn’t move it. Still, there were only two green gear lights.

I lined up on final, thinking, “Put it down easy, easy, very gently,” and while I was on final the approximately eleven-year-old tower boy started calling out to the firefighters “Crash One, Crash Two proceed on taxiway, alpha.”

Holy Sierra. “Crash?!” Could you not have thought of a better call sign? Like maybe, “Rescue One, Rescue Two,” or heck, “Big Green Truck One.”

I landed uneventfully. On the rollout, the now nine-year-old tower boy called out over the radio “All looking kinda good?”

I keyed the mic button to reply but could not speak. I had no moisture in my mouth at all—turns out you need that to speak. I closed my mouth—a rarity—and moved my tongue around and around and finally, I squeaked out, “All good.”

I taxied off the runway onto a taxiway—avoiding the eleventeen-foot-high snowbanks—and shut down. The “crash” guys rolled up in their big green trucks and their firefighter outfits, looking every inch like heroes. They seemed glad to “get out of the house,” so to speak, and I sorta felt like they owed me one for getting them out and entertaining them, if only for a few minutes. Maybe they should contribute to the repair bill?

I talked with the seven-foot-tall rescue guys (every rescue person, and every instructor when you’re a new pilot is seven feet tall) and they were commenting on the weird paint job on my airplane, which looks like an American flag. I said,”You think that’s weird, look underneath. There’s a full-size bald eagle painted on the bottom.” So they got down on their hands and knees and looked up underneath the fuselage and wings, and sure enough, there was.

COMING DOWN

After chatting with them a bit, I walked to my hangar to get my robot aircraft tug to tow my airplane to the non-heated sheet-metal deep-freezer box called, in North Dakota, a “hangar.” I walked along in the 10-degree F air with the wind blowing, no hat, no gloves, light jacket. I was so happy to be safe on the ground, it felt like summer to me. I noticed the birds, the clouds, felt the breeze, heard the noise of a car far away on a road.

I started singing.

Matt Johnson is a former U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot and KC-135Q copilot. He’s now a Minnesota-based flight instructor.