M y career in aviation started in 2006, when I earned my private pilot certificate flying in some of the most congested airspace in the world. Today, I fly mainly Cessnas, but over the years have logged time in Pipers, Diamonds and other aircraft types. My passion for aviation took me to the point where the FAA accepted me as a trainee and I started a career as an air traffic controller in 2014.

Tom Turner’s February 2019 article, “The Big Picture,” highlighted for me that we should find ways to continuously improve the way we operate within the National Airspace System (NAS) and one way I can help—to give back, if you will—is to try explaining to pilots more about what goes on in the towers, Tracons and Centers throughout the U.S. It’s not mysterious or difficult to understand, but it may be different from what you have been told, or told to expect.

A different perspective

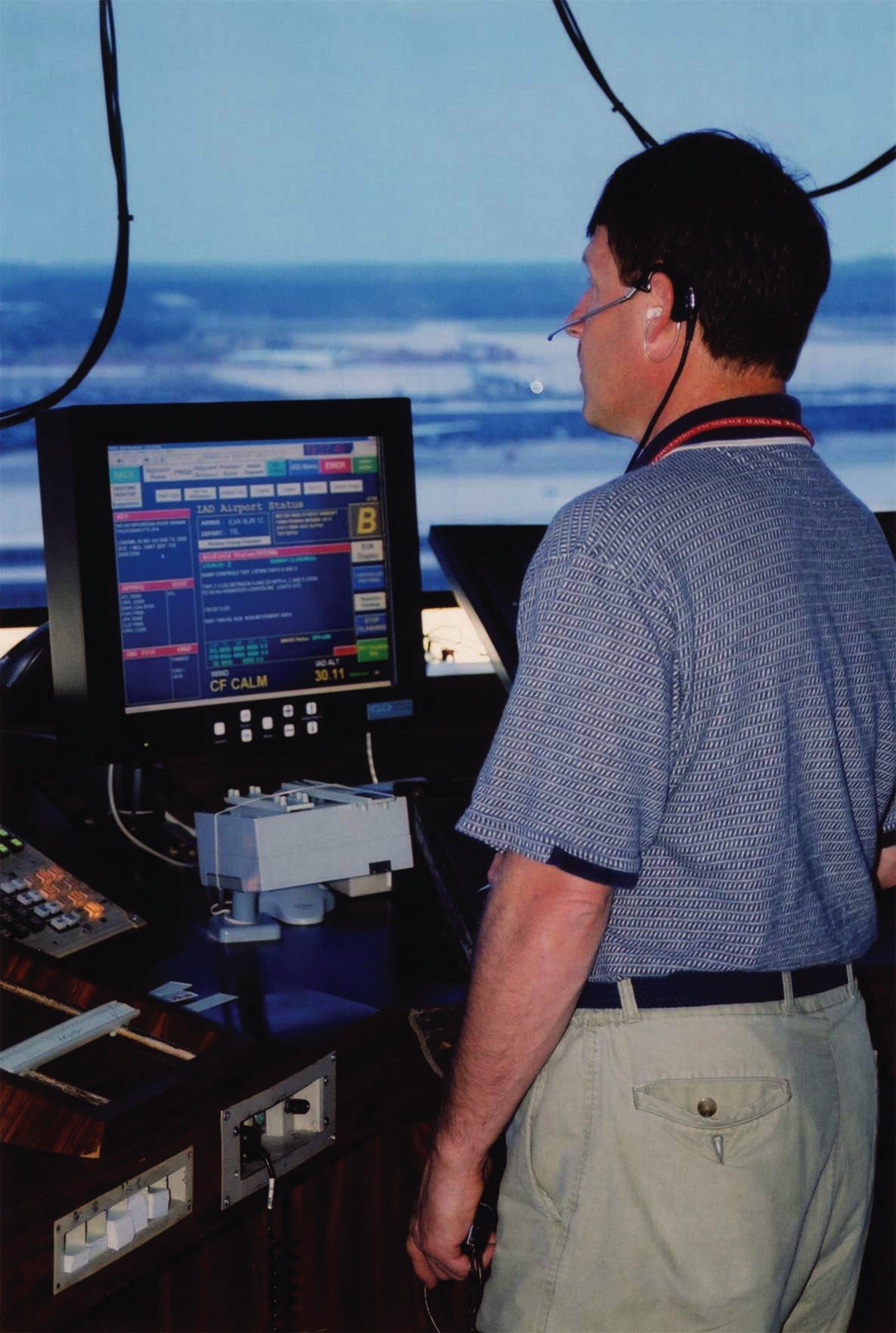

The typical pilot may not have the ability to ask their questions or speak their concerns to an air traffic controller, or even be able to understand what goes on with controllers on a daily basis. Having us talk fast and speak to multiple aircraft, as it seems to be all at once, to make the operation a fine choreography of movement in the sky all stems from high-quality training, patience and having a safe mindset. A busy session is determined by the volume of aircraft and the complexity in which they arrive, depart and remain in the pattern.

A perfect example is the high volume of traffic in Class B airspace—say, 60 jets an hour, arriving and departing—may have low complexity, since most of the traffic is using the same airport and enter and leave the Bravo over well-defined and published fixes. On the flip side, tower controllers in Class D airspace may experience low volume—20 aircraft an hour, perhaps—but high complexity due to many factors.

Those complicating factors can include a mix of many different aircraft types, all flying at varying speeds and in multiple directions, terrain and even adjoining airspace. Rarely are inbound VFR aircraft sequenced for arrival by a Tracon, simply because they’re not talking to ATC before nearing the Class D airspace. Situational awareness and expectations on both sides of the mic determine how flights are handled.

Come in, get down

It may sound odd, but to me one of the most rewarding aspects of being a controller is the fun I have organizing the clutter of aircraft coming at my airport from all directions, just waiting to test my skills each and every day. The amount and variety of different general aviation aircraft always make it challenging. That said, there are a few good habits pilots may want to adopt to enhance awareness and to alleviate biased expectations.

First, before your initial call-up, listen to the complete automated terminal information system (ATIS) or automated weather information (AWOS/ASOS) recording. This provides weather and other pertinent information, including Notams, for the airport. It’s also a legal requirement to use the runway during tower operating hours. The information in the ATIS, not just the code, must be received prior to arrival or departure at towered airports. If flight following is used, then the appropriate approach control should be advised of the receipt of information; if not, advise the tower on initial contact.

Second, listen to the frequency before keying the microphone. If it’s quiet, it might be too good to be true—especially around high-volume areas such as Southern California. Each time I fly and hear nothing upon first selecting a new frequency, a technique I use is to key the microphone twice before transmitting. This preps the controller that someone is out there not already on frequency while also checking that at least the aircraft radio will break squelch.

Third, listen to the frequency as you approach the airport and try to paint a picture of the other aircraft and how the controller is directing traffic. The idea is to establish and maintain a high level of situational awareness. To the frequent fliers, you know when I talk about the voice of annoyance, that voice that says only one word—”Blocked!”—is all too common. Sometimes, as I control traffic, while fighting the urge to face palm, I wonder if that voice comes standard on some of these aircraft. Listen to each other and listen for instructions; keep it short and simple.

Pilot Responsibilities

The FAA’s Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) contains a wealth of information useful to pilots when trying to understand the controller’s role in the ATC system. Some excerpts from the AIM’s discussion of a pilot’s responsibilities when working with ATC include:

Record your clearance

Especially when conducting IFR operations—but it’s also a good idea when VFR—make a written record of your clearance. ATC may find it necessary to add conditions and expects you to know the content of previous clearances.

Read IT back

Pilots of airborne aircraft should read back those parts of ATC clearances and instructions containing altitude assignments, vectors or runway assignments. Reading back the information helps reduce communications errors—and pilot deviations. Include the aircraft’s identification in all readbacks and acknowledgments.

Initial readback of a taxi, departure or landing clearance should include the runway assignment, including left, right, center, etc., if applicable.

Accept It Or Refuse It

A controller can’t know a pilot’s skill level, nor the flight conditions he or she is facing, nor the aircraft’s limitations. Thus, it’s the pilot’s responsibility to determine if a clearance can be accepted. If it can’t, advise the controller of what parts of the clearance are unacceptable and offer an alternative. —J.B.