Most of us fly from nice, long, level and wide paved runways with minimal obstructions. Whether for fun, variety or vocation, others of us use less-developed runways and airports, most notably back-country airstrips. All of us know that whenever we’re off the beaten path—a term holding different meanings for different people—the risk of whatever flight operations we engage in goes up. While I’ve done my share of off-pavement operations, most of them were to or from well-maintained grass runways with clear approach and departure paths, or from sometimes-remote lakes using a seaplane. So I’m a little familiar with the “roll your own” style of flight operations in which many pilots engage.

One of the things I’ve noticed from watching other pilots experienced in such operations is the routine with which they approach what, for me, are non-routine things. I understand I’m a spoiled flatlander, but operations in high density altitude conditions to and from locations I normally would reject for an emergency landing seem to leave little margin for error, at least the kind of margin with which I’m accustomed. So I’ve always have great respect for back-country pilots, the airplanes they fly and the challenging locations they turn into a routine.

One of the reasons for my respect is the need to extract from the airplane all of the performance available. When operating to and from those aforementioned paved runways, most of us rarely need all of that performance. But when flying off the beaten path, those needs change, and “all of the performance” becomes the new normal. Here’s an example of why, and what can happen when an otherwise routine operation—at least for the pilot—is off by a few feet.

Background

On April 10, 2015, at about 1225 Mountain time, a Cessna T210M Turbo Centurion collided with trees shortly after departing the Upper Loon Creek USFS Airport located in the Salmon-Challis National Forest near Challis, Idaho. The private pilot and three passengers were fatally injured; the airplane sustained substantial damage. The flight was departing, having arrived at the remote strip earlier the same day. Visual conditions prevailed.

The pilot had flown into Upper Loon Creek frequently, although this was his first visit since the previous fall. The pilot’s spouse recalled he typically would land to the southwest and depart to the northeast. When taking off, he typically would make a straight-out departure until reaching a ridge where he would begin to circle in an effort to gain altitude.

There were no witnesses to the accident, nor did anyone at a nearby ranch hear the airplane depart.

Investigation

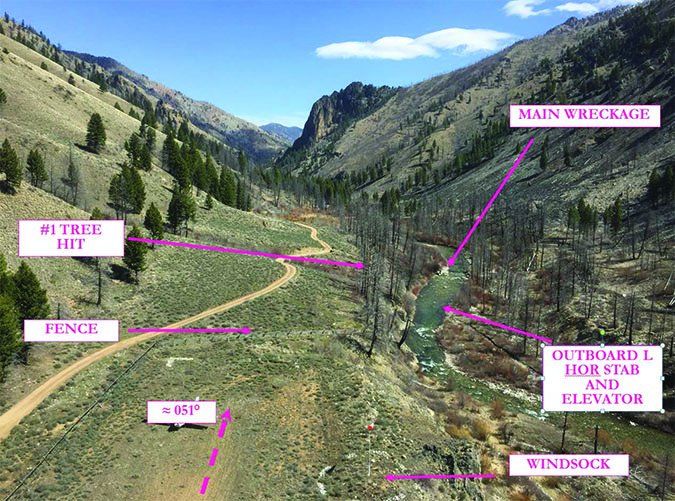

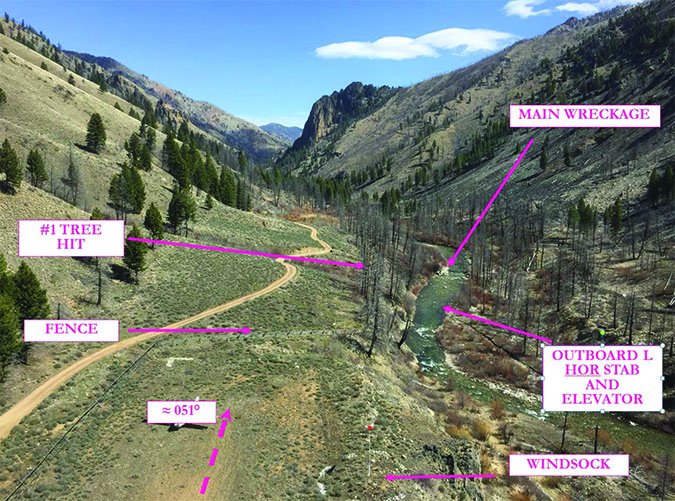

The airplane wreckage was discovered partially submerged in a shallow creek adjacent to the 2500-foot-long runway. The fuselage and a majority of both wings was consumed by fire. The airplane came to rest inverted, with a debris path oriented on a 080-degree magnetic heading. The main wreckage—the majority of the airframe and engine—was about 600 feet from a fence located at the end of the northeast runway.

The first identified impact point consisted of broken tree limbs at around the 50-foot level. The tree was about 100 feet east of the runway’s extended centerline. The airplane’s nosewheel was located about 100 feet from the tree. The left landing gear tire was farthest from the debris field, on the southwest side of the creek bank. The outboard half of the left horizontal stabilizer was found in the river around the same length down the debris field as the nose landing gear. A U-shaped wrinkle in the horizontal stabilizer was about 10 inches in diameter. Airplane components were distributed along the path between the tree and the main wreckage, and beyond.

Continuity of the control cables and fuel system could not be confirmed due to thermal damage. The wing flap jackscrew’s position was consistent with the flaps being extended between five and 10 degrees.

The engine was recovered and transported to a test facility. After replacing the number 6 cylinder, several induction system components and exhaust risers—all of which displayed impact damage—the engine started normally on the first attempt. The engine accelerated normally without hesitation, stumbling or interruption in power, and demonstrated its ability to produce rated horsepower. The turbo controller was disassembled, and no anomalies were noted. There was no evidence of mechanical malfunction or failure with the airframe or engine that would have precluded normal operation.

A portable GPS navigator was found in the wreckage. The accident flight began at 1224:38, with the speed gradually increasing to 80 knots and the airplane climbing about 50 feet above the runway’s 5500 feet msl elevation, reaching 5567 feet at its highest point. Data from the device was used to plot nine previous takeoffs from Upper Loon Creek. All nine flight paths were to the right of the accident flight. The greatest deviation was 111 feet; the average was 56 feet to the right.

Weather observed about 14 nm southeast of the accident site and about 25 minutes after the accident included a temperature of 10 degrees C, with wind from 180 degrees at seven knots, gusting to 15. Density altitude at the time of the accident was computed to be approximately 6046 feet.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined this accident’s probable cause(s) to include: “The pilot’s attempt to depart in conditions that resulted in the airplane having insufficient performance capability, which resulted in a collision with a tree.”

The manufacturer calculated the airplane’s takeoff performance using presumed weights and recorded environmental conditions. The distance required to clear a 50-foot obstacle for a takeoff with a five-knot tailwind from a dry grass runway was computed to be about 2675 feet. The actual distance from the area where the pilot began the takeoff roll to the first impacted tree was about 2625 feet, indicating “the airplane did not have the sufficient performance capability to climb over the tree,” according to the NTSB.

Based on his previous flights out of the strip, if the pilot had flown 50 more feet to the right, and/or had another 50 or so feet of total distance between the start of the takeoff roll and the initial impact point, I’d be writing about a different accident this month.