Oops. When getting a tattoo or an amputation, oops is a word you do NOT want to hear. When talking to air traffic control, it is not a word you want to find yourself saying. It probably means that you have done one of two major snafus: an altitude/heading bust or, if VFR, an airspace bust.

Picture yourself on a business trip to an extremely busy part of the country like the northeast. The weather is nothing but the cool, crisp blue skies of fall, a little wind, and the landscape burning red and orange as the leaves turn to the vibrant colors of the season. Your meeting has gone well, and it has finished early enough for you to be home before dark. As an instrument-rated pilot and the owner of a complex single-engine airplane, you can file an IFR flight plan or you can go VFR.

The advantage to an IFR flight plan is that you will be under the full umbrella of radar services provided by the FAA. The disadvantage is that, due to traffic separation requirements at two major airports near your departure point, there will be a delay – and there is no way to calculate how long it will be or how much fuel you will burn in the meantime.

The advantage of VFR is that you can fly in radio silence and enjoy the scenery and you can leave immediately. The disadvantage is that you may not be able to get flight following for some time, especially since you are going to depart the area of the Class B airspace fairly quickly.

Yes, It Matters

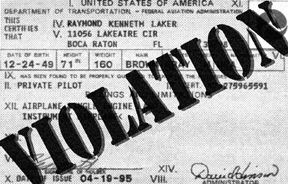

A pilot recently spent some time in counseling to prepare for an appointment with the FAA to review airspace because of a violation of the airspace rules, particularly the rules regarding Class D airspace that underlies Class B airspace. Though you may consider minor airspace infractions an inconvenience rather than a safety hazard, this pilot was surprised. Instead of getting a new frequency, he was given a phone number.

All of us can remember trying to learn the vagaries of the various categories of airspace. An airport in Class D airspace is a relatively small airport that has a control tower. Compared to Class B and C, Class D is the smallest of the three tower designations.

Class D airports have limited radar coverage, and their airspace is usually a circle that is 4.4 miles in diameter and extends to 2,500 feet agl. As usual, the dimensions are not carved in stone, but you will find that the exceptions prove the rule.

As with any controlled airport, the pilot must request approval before taxiing on the ground, departing or landing, and two-way communication must be established prior to entering. Both the FARs and the AIM discuss in detail some of the required equipment, speed and communication restrictions.

Class B is big, the Grand Central Station of airspace. The upside-down wedding cakes are only found at the nations biggest and busiest airports, and they include the full extent of the FAAs radar coverage. VFR aircraft wanting to enter Class B airspace are required to hear the words cleared to enter or cleared into prior to penetrating the boundary; simply establishing communication is insufficient.

Like in Class C, Class Bs radar services and airspace transition are based on the workload of the controller, and therefore are at the controllers discretion. Aircraft landing at an airport within Class B under VFR conditions will eventually get in, but there may be a wait.

The ABCs are a simple matter, but leave it to the FAA and the writers of FAA-speak turn them into some complicated airspace. While the naming of airspace is vastly more simple than it once was (no more TCA, ARSA, PCA), many of the rules are the same, and if you arent careful, you can find yourself in trouble.

An infant does not need to learn every nuance of language and numbers before being allowed to leave the house. He can practice at will, and people will willingly and gently help and correct. Not so the aviator. The FAA has deemed that you, as a pilot, will not be issued a certificate before learning the difference between a Class Bravo circle on your sectional versus a Class Charlie circle. You will know the ABCs of airspace classification and the 123s of cloud clearance and altitude limits, or you shant fly.

But in the Real World

Sometimes, particularly in the northeast and in southern California, several airports may be put under the protection of a single piece of Class B airspace. For example, around the nations capital, Baltimore (BWI), Washington-Dulles (IAD), Washington-National (DCA) and Andrews Air Force Base (ADW) are all primary airports in the Baltimore-Washington Tri Area Class B. In New York, LaGuardia (LGA), Kennedy (JFK) and Newark (EWR) are all part of the New York Class B. The FAA has done this because the airports involved are all in very close proximity to one another, and in some instances, the use of certain runway combinations between the various airports can cause potentially serious traffic conflicts.

The best solution in cases like this is to enjoin the various Approach and Departure control facilities and establish procedures that will minimize conflicts. Often, the FAA does this with a Letter of Agreement, which is an agreement between two or more facilities essentially stating how controllers will coordinate traffic so as to keep workload reasonable and conflicts down while keeping the traffic moving. If you ever fly somewhere like New York, and start getting weird vectors, odds are that the controller is simply adhering to the rules of the LOA.

Challenges arise when Class B airspace overlies Class D airspace. Such is the case with Newarks Class B and Teterboro (TEB), N.J.s Class D. To make matters worse, EWR has parallel north-south runways and TEB lies right on the final approach to runway 19 at EWR. The Class D airspace is wedged into the Class B airspace just above it, and for VFR aircraft, there is very little room for maneuvering your way out.

Our Intrepid Pilot

As an instrument-rated pilot, our subject has made it a habit over the last 20 years to fly almost entirely on IFR flight plans because he likes the security of having the gamut of ATC and aircraft separation services at his disposal, without being forced to request flight following.

On the day in question, he was at TEB on a business flight, and as he prepared for his return home, in the direction of Baltimore, he decided to depart VFR because of the aforementioned clear skies and delayed IFR departure due to traffic constraints with Newark Approach. He knew that after departure, he was going to have to make immediate contact with Newark – and he did. Sort of.

This fellow is also a frequent user of Martin State Airport in Baltimore, a small Class D reliever airport to the northeast of BWI. Like TEB, Martin is underneath the Class B, but it is not wedged in nearly as tight as TEB is in New York. At Martin, the Class D airspace directly over the runway is also the bottom of the 2,500 feet ring of the Class B. In New York, the TEB Class D reaches up to 2,500 feet, but the Class B ring around the airport comes down to 1,800 feet, a 700 foot overlap.

As busy as BWI can be at times, Martin is usually pretty quiet, and the controllers are fairly laid back. As a matter of routine, when you depart VFR, you will almost always hear them provide you with a frequency on which to contact Baltimore Departure control.

Teterboro, on the other hand, is extremely busy due to high-speed corporate jet traffic, and Newark is even worse due to the airline traffic. Because of this, the TEB tower will not necessarily provide you with a contact frequency for Newark Departure control. This is what got the pilot the phone number.

He had gotten so used to the courtesy of Martin handing him a frequency when he operated VFR that he expected one when he left TEB. Instead, he took off and climbed merrily into the Class B airspace, sans the requisite permission.

When he knew he was out of the realm of the TEB Class D, he asked the TEB tower when he could expect a handoff. They gave him a frequency, he called Newark Departure control, and found himself copying the phone number.

He had flown right into the departure corridor for traffic departing Newark to the west. Did he get flight following? Oh, you betcha! He had unknowingly activated the ATC equivalent of DEFCON One. When he finally called Newark Departure, he was not only in hot water, it was boiling hot. The controllers were terse, and to the point. He had caused some potentially serious traffic conflicts.

ATC gave him a transponder code, verified his altitude and intentions, and provided a vector to clear the Class B, and dispensed with him as soon as possible. He got the flight following, but his method was not, shall we say, strategic.

The Local Flavors

This situation illustrates clearly what good flight planning must include – whether IFR or VFR. The decision for the pilot to depart VFR in order to avoid an IFR delay was not in itself a bad one. But in deciding to leave VFR in some of the busiest airspace in the world, a pilot must be extremely cognizant of what airspace and ground obstacles are around him.

The best investment in this case is in both the local sectional chart and the applicable Class B chart. Its also cheap insurance to buy the most current Airport/Facilities Directory. Using this, in addition to the sectional chart and what aid might have been coaxed from the TEB tower controller prior to takeoff, our pilot would have been able to plan his departure more accurately. This is especially true when it comes to finding the appropriate sector frequency for Newark Departure that will help get the most expeditious clearance to climb into the Class B, if that is what is desired.

When counseling this pilot prior to his meeting with the FAA, he and his CFI discussed several ways to get in and out of TEB without bringing our nations defense system to full alert. In his case, TEB is surrounded by several other Class D airports, and trying to navigate around and between them while watching for traffic and negotiate Class B entrance with Departure control, even with a moving map GPS, can be a challenge.

The safest thing for him to do would have been to depart towards the northwest, away from the congested population centers, and away from the outermost floor of the Bravo airspace, followed by a turn back to the southwest. The additional flight time, especially in a plane that goes 150 knots, would have been minimal, probably no more than 10-15 minutes.

Knowledge of the rules in this case is critical as well. A Class D tower is not required to provide you with a frequency for departure control. In the case of an airport like TEB, an instrument-rated pilot might decide that it is smarter to take off under an IFR flight plan, with an IFR clearance – a clearance that will inevitably put him legally in the Class B – and then cancel IFR when clear of the busy airspace.

Local practice makes a difference too, because even the FAA has to bend rules and procedures for various airspace configurations. TEB and MTN are two different airports with different circumstances. It is neither right nor fair to assume that a regularly provided courtesy at one is universal.

In this case, one or two phone calls could have made a huge difference. It would have been worthwhile to call the TEB tower prior to takeoff to get their recommendations. Likewise, a call to Newark and a conversation with a controller or supervisor would have been worth the weight of the phone in gold. Equally productive would have been a visit to the flight school on the field at TEB, where a local CFI probably would have been more than happy to provide some tricks of the trade, and free of charge, at that.

Penetrating Class B airspace without permission is all too common, and it happens for a multitude of reasons. Class B airspace varies in shape from facility to facility. Pilots do not familiarize themselves with landmarks or sectional charts. Pilots fail to understand the importance of actually getting permission prior to entry…the list goes on. The important thing to remember is that Class B means Big and it means Busy. Entering without permission creates all sorts of potential traffic conflicts that can put hundreds of lives – and your certificate – at unnecessary risk.

The CFI spent three hours reviewing all manner of these operations, from arrivals to departures, and it was informative and productive for both teacher and student. It was a nice review for the instructor, because even CFIs often carry their own confusion and questions. The following day the pilot met with an FAA representative from his home district who had been briefed on the basics of the violation.

The first thing the client did was to admit his mistakes, because trying to deny them only makes the situation worse. From there, they covered all the topics that had been reviewed together, including a mock flight into and out of TEB. The FAA was satisfied, and considered him counseled and the situation closed.

All in all it was painless, educational and informative – especially compared with how it could have ended. And, as is intended, this individual will not be in this spot again.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Departure, Departure, Wherefor Art Thou?”

Click here to view “Tricks and Traps.”

-by Chip Wright

Chip Wright is an airline captain and CFII.