Advancing your ratings makes you a better/safer pilot. Weve probably all heard that statement more times than we can count, and most pilots probably accept it as an empirical truth. However, others feel that their lack of advanced ratings does not make them any less safe or competent to fly the planes they do, the way they do.

At the risk of sounding like a lawyer, the truth, I think, is that whether advanced ratings makes you a better/safer pilot depends a lot on what you mean by better and safer. Many folks equate the type of flying a pilot does or the certificates/ratings he holds with some sort of rank ordering of pilot skill/safety/proficiency.

Few people would argue that your average 747 or F/A-18 pilot would be competent to land a Super Cub on an enclosed mountainside dirt strip. But this doesnt mean the average bush pilot is a better pilot than an ATP flying jumbos on international route or a Blue Angel. I would suggest that the fundamental truth of that basic statement really depends on the parameters within which it is made.

Its difficult to examine the accident rates for pilots of various certificate levels and ratings because theres no real way to tell how many hours are flown by pilots with different certificate levels in similar circumstances. For example, we have a pretty good idea of the total number of hours flown by pilots on flights deemed personal, but there is no breakdown between non-instrument-rated private pilots, instrument-rated private pilots, commercial pilots and ATPs.

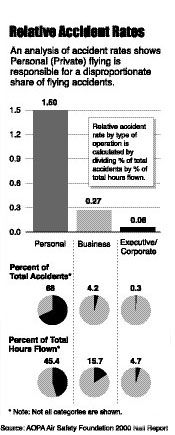

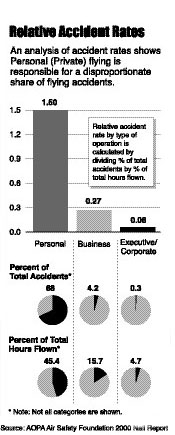

But thats not to say we cant make some guesses. You can probably assume that virtually all corporate operations are flown by Commercial and ATP pilots. Thus, the Air Safety Foundations Nall Report stats for Executive/Corporate versus Personal flying (which does not include flight instruction) come into play. The numbers for 1999 show that although Executive/Corporate flying accounted for nearly 5 percent of all GA flight hours, it accounted for only 0.3 percent of GA accidents.

On the other hand, Private flying (which would include most non-instructional flying by Private Pilots) encompassed less than half the GA hours but led to more than two-thirds of the GA accidents. This would suggest that Commercial and ATP pilots have a lower accident rate than Private pilots.

But its never that easy, and these statistics cannot be taken at face value. Executive/Corporate operations generally involve two pilots, two turbine engines, and advanced systems for navigation, communication, weather detection, and icing. Meanwhile, the average Personal flight is probably a single pilot in a moderately equipped single piston engine airplane.

Clearly, the bizjet has a lot of systems for dealing with conditions and failures for which the personal plane is ill-equipped.

Dialing it back a notch, a look at Business flying shows that it accounted for almost 16 percent of the GA flight hours, but less than 5 percent of the accidents. Since Business flying usually involves equipment more closely analogous to Personal flying, and usually involves pilots with at least an Instrument Rating and often a Commercial certificate, we are starting to see a trend, as pictured in the accompanying chart of relative accident rates for various types of flying.

Wheres the Danger?

The immediate inclination is to conclude that these numbers suggest Private pilots are more dangerous than those with a Commercial or ATP but, again, they dont take into account the advanced procedures, standards and equipment used in Executive/Corporate flying.

In fact, procedures and standards receive increased stress at each level up the certificate ladder. Items such as standardized procedures for flying the plane, crew coordination and cockpit resource management are effective ways to improve safety. When pilots go through these higher level training courses, the increased emphasis on such issues cannot help but to give them additional means to be safer pilots.

But perhaps the best indications of how ratings affect safety come from the people who stand to make or lose money on the issue – the insurance companies. Insurance actuaries very carefully study the accident experience of pilots of varying age, experience and qualification in order to decide how where to set insurance premiums.

They compare the accident histories of pilots with similar qualifications in similar airplanes to come to a highly quantified measure of risk. Insurance companies take a good look not only at the pilot, but also at the aircraft and the conditions in which it is likely to be flown.

Most insurance companies will refuse to cover a pilot in a high-performance complex single such as a Bonanza, Saratoga HP, or Cessna 210 unless the pilot has an instrument rating. A pilot doesnt need an instrument rating to fly one of those airplanes safely, but the insurance companies have found that it helps.

If one considers the PTS requirements for the various licenses and ratings, a commercial certificate seems to make more sense as a prerequisite for the pilot of an airplane in this class, as the commercial has requirements for complex aircraft operations while the instrument rating can be obtained in a Cessna 150. So why do insurance companies demand the instrument rating but give little extra credit for a commercial certificate when you go to them to insure your Bonanza?

The insurance companies have concluded that an instrument rating is necessary to safely fly these airplanes the way their owners typically fly them. Specifically, people dont get a 210 to make $100 hamburger runs on sunny Sundays. They buy it for the speed and capability to make long trips for both business and vacation travel.

Trips like this are usually planned well ahead of time, and cancellation of such trips due to weather is often a less palatable choice than skipping a spur-of-the-moment pleasure hop. The insurance companies point to cases of non-instrument-rated pilots crashing airplanes like this in IMC or very marginal VMC on cross-country trips that could have been made safely under IFR.

On the other hand, the insurance companies seem to feel that, after a certain experience level, additional licenses do not reduce the companys risk. For example, a commercial pilot with 5,000 hours is generally viewed as an equal risk as an ATP with the same experience. This begins to suggest that experience, as well as license level, is a major factor in lowering accident potential.

Tools in the Toolbox

To determine if advanced training can reduce the risk of the kind of flying you do, you must first examine what you get in the various advanced ratings/certificates.

The first thing pilots usually go for after getting their basic PP-ASEL is an instrument rating. After all the legal hoops are jumped, an instrument rating basically serves three purposes. It improves your ability to fly by reference to instruments, analyze weather patterns more effectively, and work within the ATC system.

Each of these three skills gives you more tools in your toolbox – you have greater capability than you did before. Flight by reference to the instruments goes beyond IFR flying; its also an invaluable skill even in VMC.

Summertime murk is a familiar environment to anyone who flies in coastal areas or other humid places. Youre flying in a bowl of milk, with no horizon to guide you, and about the only thing your view outside the airplane is good for is collision avoidance – and even that capability is slashed by the haze.

In conditions of reduced visibility, you must actually spend more time looking outside, as you will have less chance of seeing airplanes farther out, and therefore cant take as long a break to look inside as when you can see for miles and miles – its a matter of reduced warning time available.

You are forced to rely on the instruments for attitude reference and even navigation, yet you must spend less time looking inside to do it. Having the additional skill to be able to quickly scan and interpret your flight and navigation instruments is a big plus in this situation.

Weather smarts is another area where its tough to get too much. A thorough understanding of weather is probably the best defense a pilot has against the continued VFR into IMC accident. If you know whats out there, its a lot easier to avoid it.

The weather training at the Private level is pretty rudimentary, and the additional weather knowledge that is part of the instrument rating helps develop the pilots ability to look ahead, in flight as well as during preflight briefing, and make a good decision about when to knock it off and either stay on the ground or turn around and land.

If you already have an instrument rating, dont get fooled into thinking that VFR into IMC cant happen to you. A large percentage of such accidents involve aircraft piloted by instrument-rated pilots. Sometimes theyre not proficient, sometimes they dont bother checking the weather, and sometimes they get caught while waiting for a pop-up clearance.

Perhaps the most important skill gained with the instrument rating is improved proficiency in working with ATC. Many pilots have a strong aversion to working with ATC, and usually its because they arent very good at it. They may be intimidated by the rapid-fire style of controllers in busy airspace or an uncertainty over whether theyll sound like amateurs.

They cant make their requests in a fashion that elicits a cooperative response from the controller, and that makes it worse. I once heard a busy controller tell a VFR pilot, If you cant listen as fast as I talk, I cant have you in my airspace – remain clear of the Class Bravo Airspace, maintain VFR, squawk 1200, frequency change approved, good day.

Working with controllers while flying VFR gives you more information and more options. By being in the system you get better access to weather and traffic information, and youll often be cleared through airspace youd have to fly around if you werent talking.

Anything that expands the space available to you is good, especially if it lets you fly where the visibility is better, the air smoother and the traffic more predictable. Simply eliminating the additional stress of low-level turbulence when youre performing basic pilot functions like map-folding makes it easier to avoid task saturation – a major factor in many accidents.

We can extend these effects to the Commercial certificate. The two skills the Commercial will enhance are precision control of the airplane and, again, expanded weather knowledge. While a PTS chandelle or Lazy 8 isnt the most useful maneuver in the world, it requires concentration, skill and precision.

Also, the certificate requires better precision in landings in controlling the touchdown point – both down and across the runway – which can be a major factor in avoiding runway accidents. Runway loss of control continues to be the biggest cause of general aviation accidents.

The commercial standards for landings are significantly tighter, requiring speed be maintained in a 5 knot window instead of the +10/-5 tolerance for private, as well as touching down within 200 feet beyond a designated point instead of 400 feet. In addition, the instructor giving the training will likely insist on consistent landings on the centerline rather than even a foot or two off.

Given the number of runway accidents that show up, these precision landing skills are important to improved safety.

Advancing to an ATP certificate means the standards are stricter in virtually every phase of flight.

But Do You Need It?

None of this is to say that a pilot has to get advanced licenses or ratings in order to be a safe pilot.

For the sake of argument, consider Charlie, one of the typical pilots who hang around our local airport. Charlies a retired schoolteacher with a Private certificate earned back in the pre-SSN certificate number days, and his starts with a 1.

Hes got about 2,000 hours in his logbook, dating back nearly 40 years. For him, flying has never been anything but a weekend hobby, consisting mainly of $50 hamburgers with his wife or a friend in the 1966 Cessna 150 hes owned for over 20 years. He used to take some of his high school students up for introduction to flying rides, and continues to do so as part of the EAA Young Eagles program.

He limits his flying to about a 100-mile radius of his home airport (a small, non-towered field with about 40 airplanes based there), sticks with sunny days, and stays on the ground when the wind is bending the trees. Hes a regular at the FSDOs Safety Seminars and each spring he gets with a local CFI and brushes up on all aspects of the flying he does, getting a BFR signoff whether he needs it or not.

A couple of generations of CFIs agree that Charlies a far better stick-and-rudder pilot than they are. Is it likely that adding an instrument rating or upgrading to a commercial license will make Charlie a better/safer pilot?

On the other hand, a newer member of the regular set is Steve, a local businessman in his late 30s who took up flying two years ago as a means to further his expanding business and visit his vacation home a few hundred miles away. He got his Private ticket pretty quickly in a C-152 and moved up to the C-172 and C-182 as fast as he acquired the hours to satisfy the FBOs insurance requirements.

Now Steve is looking at a used but fairly recent Bonanza in order to get where hes going faster on business trips and be better able to haul his growing family up to the cottage by the lake. Does his situation make it seem more likely that upgrading will improve his safety or his skill?

The Real Advantage

Another reason why advancing your certificates/ratings can be a factor in enhancing your safety is that it will force you to spend time under the tutelage of a CFI and then take a practical test to FAA standards from a DPE or FAA inspector. This review and examination of both the knowledge and practice of piloting will also serve to identify and fix any weak areas you may have. And this will go beyond the obvious requirements of the particular practical test you are taking.

Even the instrument practical test forces you to ensure that your landings are up to speed, since landing out of an instrument approach is a specific task in the instrument PTS. In fact, a study done about 10 years ago by Baltimore area CFIs Harry Kraemer and Dave Moslein found that crosswind landings were among the top reasons applicants had failed instrument practical tests locally.

It also seems intuitive that the type of pilot who works to advance his licenses and ratings is also the type of pilot who takes more seriously the need to continue to hone his skills and knowledge long after getting that initial pilot certificate.

These are the folks that seek out tough instructors for their BFRs and ICCs. Theyre the people who take part in the Wings program because they have the attitude that it is not a public admission of inferiority to take part in such a program. They recognize that there are new things to learn and old things they have forgotten. Only by taking part in some activity to learn the new and relearn the old can they remain safe, competent pilots.

This concept is well-accepted in many professions, from education to medicine, where professionals in those fields are required to participate in some manner of continuing education in order to maintain their professional certification. That advanced training could be an additional degree, certification in some specialty of their profession, or simply training seminars in the latest information in new techniques or findings in the field. Whatever it is, it forces the individual to keep the sharp edge on his knowledge and skill.

Thus, training for advanced certificates and ratings helps create better, safer pilots simply by the fact that all your knowledge and skills need to be up to the standards needed to continue to pass checkrides. It also gives you the opportunity to be exposed to the latest changes and advances in techniques, rules and equipment.

For example, GPS is now a part of most instrument rating course materials and CRM techniques are part of the human factors section of commercial courses. Those who advance their licenses and ratings are exposed to these items, which can improve their skill and safety.

Those who do not seek out exposure to such advances may be presented with equipment they do not know how to use properly or fail to learn new concepts that can make them safer pilots. While much of this can be picked up from independent research and reading, its never the same as proper training.

Theres also a lot to suggest that certain types of advanced training that does not gain you any new paper from Oklahoma City may have considerable value.

Over the last few decades, there has been increasing concern about the ability of all pilots from Cub drivers to airline captains to cope with upsets – the recovery from extremely unusual attitudes due to turbulence both man-made and natural.

Wake turbulence and clear-air turbulence have caused or contributed to a whole string of accidents ranging from light GA airplanes to airline disasters. United Airlines was one of the first to add advanced maneuvers to its recurrency training syllabus, and a wide range of flight training schools are adding basic aerobatic and specialized emergency maneuver courses to their offerings.

Comments from pilots whove taken these courses suggest that they have substantially improved their ability to recover from such situations, as well as improving their basic flying skills. Thus, its not only license/rating courses which make you better/safer but also just about any training that sharpens your flying and adds tools to your aviation tool kit.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Tricks and Traps.”

Click here to view “Checkride Advice.”

-by Ron Levy

Ron Levy, ATP, CFI and veteran of 11 license/rating checkrides (including 4 with FAA inspectors) is director of the Aviation Sciences Program at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore.