by Ken Ibold

Much has been said about the perils that face pilots when they have little experience in an airplane model. While thats certainly true, the dynamics of where those risks lie vary, depending on the pilots experience and the kinds of airplanes involved.

Most trainers, for example, are notably docile – especially when it comes to traffic pattern manners. Sporty airplanes with nimble handling have corners of their flight envelope that can bite even experienced pilots. Advanced traveling machines have systems complexities and operating nuances that require study and familiarity.

Combine an airplane with spirited, but quirky, handling, a low-time pilot with low time in type, and you can sense the potential for danger. Unfortunately, its a potential that is too often realized.

The most poignant description of the crash of a Grumman AA-1C Lynx came from a pilot in the traffic pattern with the ill-fated flight.

The weather was great for the Tuesday afternoon flight at South Jersey Regional Airport in the summer of 2001. The winds were right down runway 26 at 6 to 10 knots. Although the airport does have periods of intensive flight training, there were three airplanes in the air, and a helicopter pilot was preparing to depart.

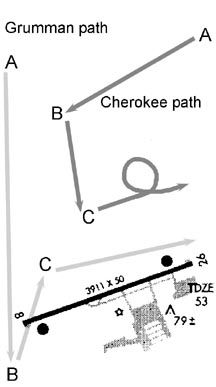

According to one witness, a Cherokee pilot flying into the airport, a Cessna was on right downwind for runway 26 at about pattern altitude and a half-mile off the side of the runway. The Grumman was flying to the south at about 1,800 feet and was approaching the departure end of runway 26.

The Cessna pilot announced downwind on the common traffic advisory frequency and the Cherokee pilot began a left turn and descent toward the airport to enter a right downwind for the same runway. The Grumman had passed to the south of the airport near the departure end of runway 26.

The Cherokee pilot said he saw the Grumman turning back toward the airport about the time the Cherokee was preparing to enter a midfield downwind. Shortly after he announced his downwind entry, the Grumman called entering a right base for runway 26.

That statement is what brought my attention to the Grumman since I saw no other plane in the pattern and he was actually in the position of a right base for runway 8, the Cherokee pilot told investigators. Now [the Grumman was] slightly lower than myself at approximately 800 feet. I watched the Grumman out of the window as he continued to cross the end of runway 26.

Perhaps mystified at what was unfolding, the Cherokee pilot turned downwind at pattern altitude and about a half mile to the side of the 3,900-foot runway. He announced again and noted the Grumman, now on a right downwind, overtaking the Cherokee from below.

When the Grumman disappeared below the Cherokees right wing, the witness broadcast, Cherokee turning left 360 to give way to the camouflage Grumman on right downwind. The accident pilot replied, Roger that.

The Cherokee pilot completed the turn and saw the Grumman at about 300 feet agl and about 100 yards from the side of the runway.

As I watched him, I was anticipating that he was going to initiate a climb since he was in no position to execute a right turn to the runway, the witness said. The pilot announced he was turning right base. Personally, I was in disbelief he was going to attempt to land on runway 26.

The Grumman banked sharply and steeply – in excess of 60 degrees – and the airplane almost immediately entered a spin estimated to last 2 turns before crashing. The pilot and passenger were killed.

Out of Practice – in Anything

If it sounds like the pilots actions revealed a lack of proficiency, his logbook revealed that might indeed have been a factor. He had logged only 13.8 hours in make and model, with none of that in the preceding 90 days.

The pilot had received his private certificate more than 10 years earlier, and at the time he passed his checkride he had logged 141.8 hours total time, with 36.3 hours as pilot in command. At the time of the accident, he had logged 319 hours, with 202 hours as PIC.

In the previous 12 months he had flown 14.2 hours and his last flight had been a month earlier.

In the hands of an unpracticed pilot, the Grumman would have been a handful. The AA-1C is an unusual design that trades stability for spirited handling. In addition, some design characteristics make it less forgiving than other two-seat trainer designs.

For example, the airplane was made to go fast. Equipped with a small engine, small wings and a cruise prop, it has a tendency to build induced drag quickly if the speed gets too slow – and the stall speed is a relatively high 60 mph with flaps down.

It will spin easily – although intentional spins are prohibited. Spin recovery can also be problematic because the fuel tanks are the inside of the tubular wing spar. Once spin rotation starts, fuel moves to the wingtips and can make the spin unrecoverable.

The combination of low altitude, full flaps, tight turn, handling qualities and pilot inexperience set the stage for an accelerated stall or cross-control stall, either of which can break into a spin in a flash.

The abrupt and aggressive turn toward base reported by the witness raises the possibility of an accelerated stall, which occur at higher airspeeds than unaccelerated stalls. Accelerated stalls can be severe even at altitude; close to the ground they tend to be unrecoverable in most situations.

The stall/spin potential is even greater if you consider the ramifications of an uncoordinated turn – a common response by pilots trying to avoid overshooting the runway.

Cross-control stalls are most likely during poorly planned turns in the traffic pattern. Typically the nose pitches down, the inside wing drops and the airplane can roll inverted. The chances of recovery from pattern altitude are virtually nil.

The fact that the pilot racked in such an extremely steep bank implies that the stall, when it happened, would be quick and severe. The airplanes relatively high stall speed and light control forces, coupled with the pilots unfamiliarity with the type, make it easy to imagine how this one got away from him.

But in many ways, the accident was set up before that turn toward the airport.

Recall the pilot reporting entering a right base for runway 26 when the witness said he appeared to be in position to make a right base to the opposite runway. He wouldnt be the first out-of-practice pilot to set up for landing in the wrong direction.

At that point, it appears he realized his error and came back to the proper downwind for 26, for which right traffic is specified. At that point, however, he displays attitude, lack of judgment or just plain ignorance about traffic pattern protocol.

Overtaking traffic ahead and apparently descending to cut off other traffic is bad enough, but the cavalier response to the witness pilots announcement that he was giving way implies that the pilot was carrying a chip inside his headset.

The two-seat Grummans have a rabid following and fill an interesting niche in general aviation. However, its clear by considering the accidents in these airplanes that familiarity and good instruction are crucial in order to operate them safely.

For example, an undue number of accidents in two-seat Grummans involve low-time pilots. While thats not unusual given their pseudo-trainer nature, relatively low price and sporty handling, the accident rate drops dramatically for pilots who have undergone the proficiency training offered by the American Yankee Association, a type club.

The NTSB report does not specify who gave the pilot his checkout in the airplane, but with no time in type within 90 days, most of the lessons from that checkout were likely lost.

Low time in type is a disease that can be cured with a little practice. Pattern errors that lead to steep turns and rude behavior can be brushed off as a mark of inexperience.

A pilot who logs 177 hours in 10 years may fly 1.5 hours every single month may, in fact, have acceptable proficiency for some kinds of flying, depending on how those hours are spent. More likely, however, such a pilot is one who does not take seriously the challenges involved in aviation – as if an airplane is a vintage car you can take for a Sunday drive when the weather is perfect.

When that unfamiliar vehicle is spirited and quirky, however, the challenges escalate far too fast for the unwary to conquer.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Aircraft Profile.”