We all know the hazardous attitudes the FAA wants us to understand. Concepts like anti-authority, impulsivity and invincibility have no real place in the cockpit. Now, I’m going to add one more: the desire to be helpful, or the motivation to please others. One of my big motivations in life is to be helpful to others. I enjoy writing for this magazine, for example, because it is helpful to other pilots. I also get great pleasure in being a solution to other people’s problems.

Sometimes, however, trying to be helpful has the opposite effect. Rather than help get someone out of a tight spot, you become ensnared in one. This is my mea culpa confession—and the story of how we need to add helpfulness to those hazardous attitudes.

A Much Worse Day Than Mine

I was flying into Logan, Utah, to pick up cargo that needed to be in Salt Lake City. As I was arriving, a brand new CubCrafter’s XCub with only 17 hours on the airframe was arriving on its maiden flight from the factory. Its pilot groundlooped while landing on Runway 35, closing the airport. I was in the pattern when it happened. The pilot reported the incident on CTAF.

Unfortunately, the FBO missed hearing the repeated distress calls from the damaged aircraft requesting assistance. I radioed to the distressed aircraft to confirm no injuries and the state of the aircraft. I let the pilot know that someone would be coming and I landed on the shorter, but available, Runway 28. My first action was to let the FBO know that the disabled aircraft was urgently requesting assistance. By then, they had heard the calls and were responding. There were no injuries, but a DC-9 was scheduled to arrive shortly, so there was a sense of urgency to get the disabled aircraft clear of the only runway long enough to handle it.

As the team moved to get the disabled aircraft off the runway, the DC-9 was returning from a day trip to Jackson, Wyo. As the big jet got closer and closer, nobody on frequency was letting them know the main runway was closed. The large jet was on final when, finally, someone informed them that there was a disabled aircraft still blocking the runway. The DC-9 broke off the approach and circled a few more minutes probably burning enough Jet A to pay for the repairs of the disabled aircraft. The runway was eventually cleared, allowing the jet to land.

A Busy Day in The Bravo

With that bit of drama concluded, I picked up my loaded Cessna Caravan and headed to Salt Lake City. As I entered the Bravo airspace, it was clear from the radio traffic that I was not alone. It was rush hour. When this happens on the cargo side, ATC has to separate slower from faster traffic. Generally speaking, maintaining faster airspeeds in the mix helps ATC out more than remaining slow. That rule of thumb doesn’t always apply, though—you are occasionally asked to slow down for spacing.

The first maneuver I was asked to do was a left 360 over an amusement park at the edge the rising Wasatch mountains. This resulted in a terrain warning since a left 360 sends you toward the mountains rather than away. So I slowed my speed to ensure the turn remained tight rather than wide, which would put me into greater conflict with the terrain to the east. After one 360, I was directed to descend and follow I-15 south toward the airport.

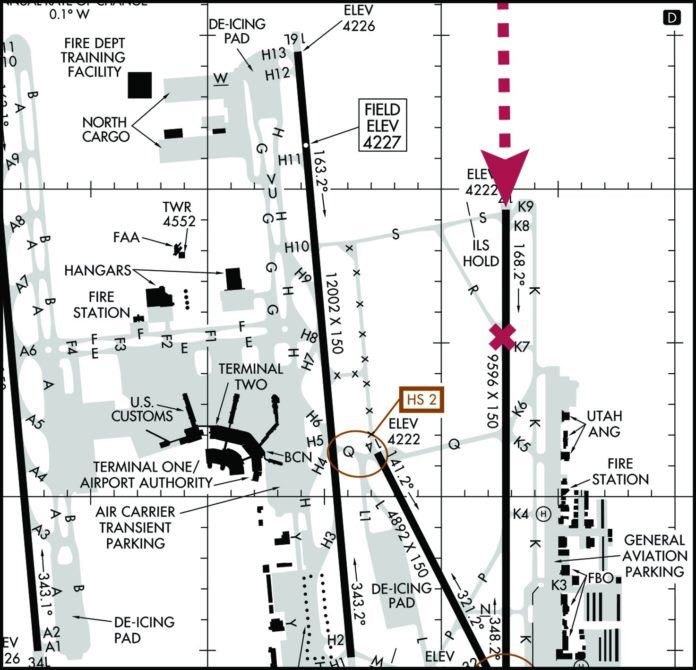

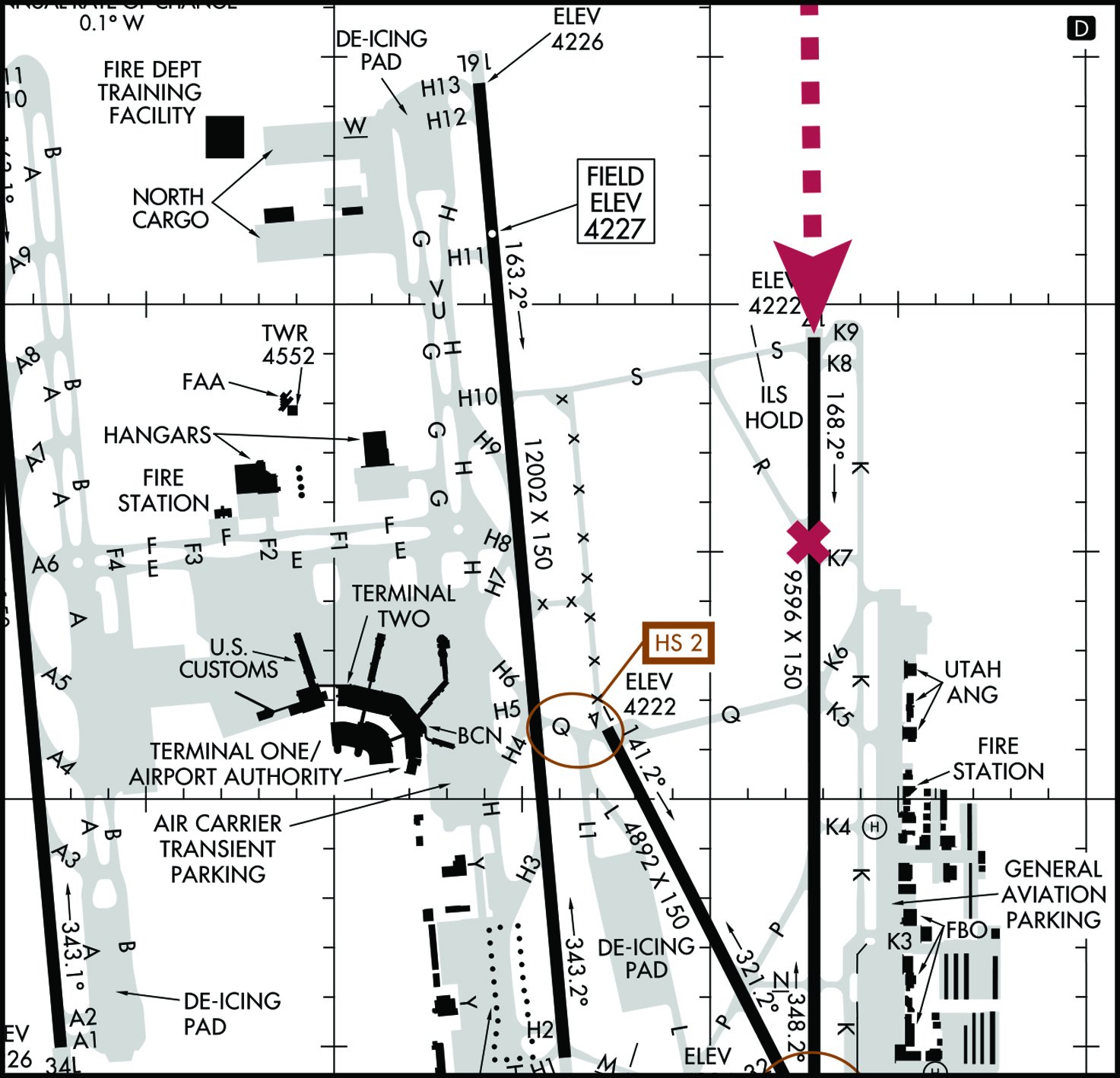

As the skyline of SLC passed to my left, another aircraft was directed to circle over the city of Salt Lake and remain east of the I-15 and out of Bravo. This was to keep them clear of me. I was told to continue I-15 South to the southern end of the airport. I was then turned back to the north and asked to descend to 5500 and reduce speed by 40 knots for spacing. I was told I would be following a slower aircraft on downwind at my 12 o’clock, a Skylane.

I reduced power and added flaps and slowed from 150 knots to around 80. I was thanked for my cooperation and was told that I had successfully matched the speed of the Skylane in front of me. The aircraft behind me was then asked to slow down as well and was told he was following a string of slower aircraft and was still overtaking because he was 80 knots faster.

This is where I started the chain of mistakes.

I finally saw the aircraft in front of me as it turned base-to-final. I was cleared to land behind the traffic I had in sight. The aircraft behind me had me in sight and so he was also cleared to land behind me. I was now the guy in the middle.

Squeeze Play

Seeing the aircraft in front of me was near the threshold and knowing an aircraft behind me was gaining on me, I decided to help ATC out and make up for the lost spacing. I put the nose down. This was not requested by the controllers, I just thought it would be helpful.

Mistake 1: Instead of flying a stabilized approach, I was doing a short approach. Instead of maintaining a constant and normal approach speed, I was accelerating to help with spacing.

My experience with the Caravan up to this point has been that when you take out the last bit of power, the prop’s flattened blades turn into a very effective speedbrake. Unfortunately, the power lever on this short approach was already mostly back, this meant the prop’s normal braking effect was counteracted by my nose-down attitude. When I came over the threshold I paid for this tradeoff: I was both high and hot. When I pulled the power all the way back, I did not get the usual dramatic speed loss I have seen on a normal approach profile.

Mistake 2: Gaining speed with power back diminishes the impact of the prop’s speedbrake effect.

When I started my flare with power full back, I floated. I had never had this happen in the Caravan, but I also had never flown this odd profile either. With power to idle, I continued floating. Speed was not coming off the way I expected from my previous (albeit limited) experience. I am still new to the plane, so the experience gap bit me.

Mistake 3: My goal on touching down on Runway 17 was to make Taxiway Romeo, making room for the landing aircraft behind me. Stupidly, I kept this goal in my head, despite the floating down the first thousand feet of runway without touching wheels. In spite of the extended float, I maintained my goal of getting off at Taxiway Romeo

When I finally touched down, I still thought I could make Taxiway Romeo. I pulled the prop to beta and applied brakes at the level that would work as aggressive but safe in my familiar 180. I then continued past beta into reverse prop. The deceleration from reversing the prop resulted in things in the airplane wanting to continue their forward momentum. Two those “things” wanting to continue forward were my feet on the brakes. At the same time, I pulled the prop past beta and into reverse. There is always a very strong left turning moment and even more deceleration in reverse prop.

When the prop went into full reverse, the brakes grabbed and the left-turning moment from reverse thrust pushed the nose left. I countered the leftward yaw with even more pressure on the right side. That was when the brake grabbed and locked, initially flatspotting then failing the right main landing gear’s tire.

Oops.

Lots more Mistakes

Mistake 4: Handling the plane aggressively. Maximum braking, full reverse prop. Why? To please a controller that didn’t even ask for it and make way for traffic behind me that is isn’t my job to separate from? That was a stupid decision. Of all the mistakes, this is perhaps the single most egregious one. Airplanes should not be manhandled, they should be gently coaxed into performance you want and need. There is no excuse or need for aggressive handling unless it is a flight safety issue. The whole sequence above was unnecessary. There was no need for the urgency.

Mistake 5: Negative transfer. The plane I have flown most is my Cessna 180, and I know how it feels on the brakes to get full maximum braking. I transferred this muscle memory and “feeling” to the Caravan. In a tailwheel-equipped airplane, the amount of braking to lock the brakes would start to impart a forward moment with the tail coming up. This feedback loop keeps you from overbraking. If you feel the tail even slightly coming up, you back off the brakes. It is something you simply feel. There is no similar feedback on a nosewheel aircraft. The Caravan also doesn’t have the same spongy feeling as you apply brake pressure, the brakes are firm when pressed and they do not get more firm as greater pressure is applied. I used the amount of brake that would work fine in my 180. But I wasn’t flying my 180! It didn’t work.

Mistake 6: Exiting the Runway on a damaged tire. This is where my opening story comes into play. I had just left an airport where a disabled aircraft remained on the active runway, creating a safety issue. I knew a plane was coming in behind me, though not a DC-9. I was also right at Taxiway Romeo as planned, except I didn’t plan on the flat tire.

At this point, I theorized that it would be both safer and less of an issue with the FAA and the SLC airport authorities if I could clear the active runway onto the taxiway. It felt like the tire was still holding and the taxiway was within a few hundred feet, so I kept the momentum to keep the tire intact. I also figured if there was still integrity in the tire, it wouldn’t hold for long. However, I thought it should be able to carry the aircraft long enough to let me get off the runway without damaging the wheel.

Mistake 7: By continuing to roll on a damaged tire, you risk damaging the rim, seeking to minimize the level of the incident ahead of preserving the equipment. Stopping immediately would have possibly kept the bead of the tire intact, which in turn would have made recovering the aircraft easier and might have lessened the expense of a dye-penetrant inspection (and possible wheel replacement if the wheel fails the test).

One vulnerability I can now see in myself is my motivation in life is to be helpful to others. The motivation to please others is one that could (and did) get me in trouble. I chose to help the controller out, knowing that a short approach and quick exit would make everybody’s day go a little more efficiently. That obviously backfired. My lack of experience in the plane combined with overly aggressive maneuvers had the opposite effect.

Aftermath

The SLC controllers now had to deal with a closed taxiway, my company has to bear the expense of replacing a part, my fellow pilots had to backfill my route and other planned flights had to be replanned. Office staff had to scramble to make new arrangements and the director of maintenance not only got interrupted on a day off, but has a new headache with my name on it to deal with on return.

It is clear that flying safely and conservatively has the least impact on everything. The plane will do better, and everyone cascading through the company will do better. To be the most helpful to others, I simply need to keep my helpfulness circumscribed by a safety envelope. As a pilot who is still new to the Caravan, that safety envelope needs to be much bigger, and my choices and actions more tightly contained in the inner circle of the safety of operations circle. The safer I fly, the fewer the negative consequences, and the fewer cascading impacts, inconvenience and cost to others.

The more vivid the experience the deeper the learning. That said, I don’t have a desire to put myself, my company and my support team through my learning curves. I would rather learn from the mistakes of others than my own mistakes. But, perhaps, sharing my experience with others will be helpful.

A flight instructor and proud owner of both a Cessna 180 and a Piper J-3 Cub, Mike Hart is now living the dream as a cargo pilot in Idaho.