Over the years, I’ve spent way too much time as self-loading cargo on airliners. Regardless, I’m always curious about what’s going on in the front office but rarely get a clear glimpse. One exception is when some last-minute maintenance is performed or connection problems result in some passengers arriving late to the gate. Invariably, Captain Speaking will come on the PA and apologize for the delay, commenting that “we’ll be ready to go as soon as we get the final paperwork.” What is the captain talking about?

In the case of last-minute maintenance performed at the gate, the captain is referring to ensuring the logbooks are updated to record the work. These days, that’s done electronically and the maintenance logs are not carried aboard the airliner. If the paperwork problem is late-arriving passengers, the issue is getting an accurate head count, loading any checked baggage and then updating the airliner’s weight and balance data before closing the door and pushing back. Operations under FAR Part 121 are among the most structured the FAA allows, and the detailed documentation the agency requires likely would be daunting to a mere private pilot in a Skyhawk. But that Skyhawk is subject to some of the same FAA paperwork rules as the airliner. What are they?

AR[R]OW

During their primary training, pilots are taught the aircraft must carry five specific types of documents. They are remembered with the acronym ARROW and decode as follows: Airworthiness certificate, Radio station license (a document available from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission, FCC, which now is only required for international operations), aircraft Registration, Operating limitations and Weight and balance data. The presence aboard the aircraft of most of these documents is relatively easy to verify. The airworthiness certificate and registration usually are in a clear plastic window affixed to an aft-cabin bulkhead or a side panel near the pilot’s seat. Typically, any radio station license carried also will be in this location. Confirming the aircraft’s operating limitations and weight-and-balance data are aboard gets a bit more interesting.

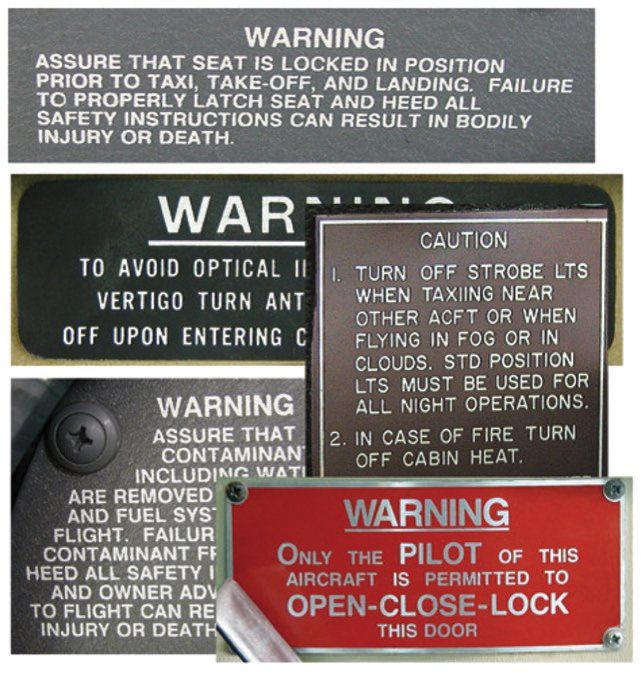

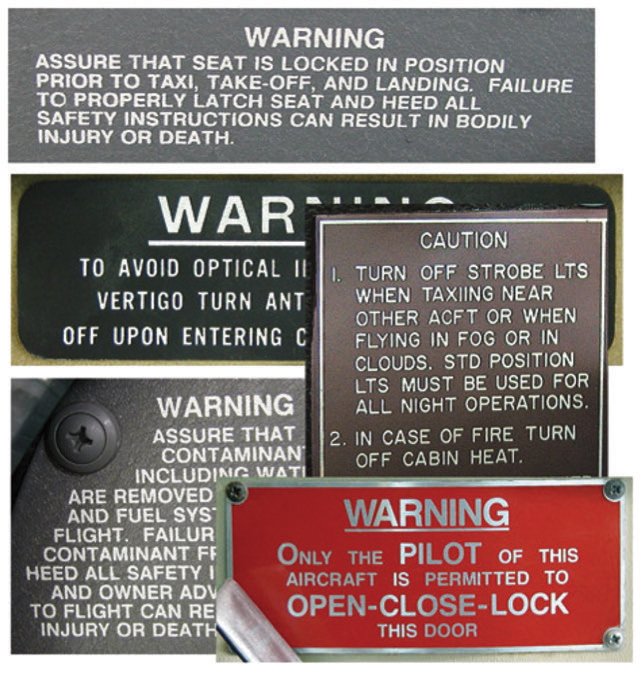

That’s because the operating limitations can consist of a wide range of placards and other notices literally scattered throughout the airplane’s cabin/cockpit and its exterior. The sidebar below highlights some of the ways placards embody the aircraft’s operating limitations, but the key thing to remember is they all are found in the current Airplane Flight Manual (AFM) or Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH). Which one your aircraft is graced with depends on when it was manufactured: A POH for most light aircraft built after 1975 is also designated as the AFM. Regardless, both are FAA-approved.

Carrying the airplane’s POH/AFM should be enough to comply with the requirement for the operating limitations to be aboard but may not. That’s because a POH/AFM may go through several revisions, and the latest revision applying to the aircraft’s serial number is the one required to be aboard. Subsequent modifications and airworthiness directives also may affect whether all applicable operating limitations are in the POH/AFM. More on that in a moment.

The weight-and-balance data depends on the equipment installed and must include the airplane’s empty weight and center of gravity (CG). The weight and balance information found in a typical “information” or “reference” manual you buy online or at your FBO isn’t updated with the latest changes that may have been made and doesn’t include the specific aircraft’s empty weight and CG. So it’s not legal to substitute for those requirements. (Consult with your aircraft’s manufacturer to determine the latest revision of the POH/AFM for your airframe.)

Typically, a separate sheet detailing the airplane’s weight and CG will be stuffed into the POH/AFM. We’re expected to perform a weight-and-balance calculation before each flight, but you’re not expected to produce the results when queried by the FAA during, say, a ramp check. Most of us simply perform the calculation for various loads once and leave the results at home. But the basic data used to compute the aircraft’s weight and balance has to be available.

Other Paperwork

Depending on the aircraft and the operation, you may be required to carry other documentation. If operating under a ferry permit (FAA Form 8130-6, which is an application for an airworthiness certificate), the form must be aboard the aircraft. Other FAA forms may be required, depending on the operation. But a major reason your aircraft may not have all the required paperwork aboard involves modifications done under a supplemental type certificate (STC) or required by an airworthiness certificate (AD).

An STC is a document approving what the FAA considers a standardized but still major alteration to a type-certificated (i.e., non-experimental) aircraft. It usually applies to a specific airframe by serial number. Examples might include an STC for an avionics installation, a turbocharger or a more-powerful engine, seaplane floats or tip tanks. Rarely is the STC document itself required to be aboard.

The FAA (via the avionics manufacturer’s STC) may require that some kind of reference manual be carried. This is likely when an autopilot or integrated navigation/communication device is installed. In other instances like a different engine, turbocharger or tip tanks, a gross weight increase may be part of the modification, which must be reflected in the weight-and-balance data. Installed equipment may also impose additional limitations—like a change to the aircraft’s design maneuvering speed, VA—which are to be placarded when replacing or supplementing those listed in the POH/AFM. An AD, meanwhile, may require its own placard or instrument markings, or perhaps a POH/AFM supplement.

The punchline—especially for club members or renters—is you may not know of all the modifications made and the documentation requirements they impose without a deep dive into the aircraft’s paperwork.

Meanwhile, don’t forget the paperwork items you need to carry on your person: pilot certificate, medical certification document and photo ID.

Placards

All the signage and text scattered around your cockpit? They’re called placards, and likely are required both to be aboard and be legible. The aircraft’s POH/AFM will detail the placards that are to be mounted throughout the aircraft and their position. A fun/not-so-fun exercise might be to turn to the Limitations section of your POH/AFM and check to see if all required placards are present.

If the aircraft has been modified by an STC or AD, additional placards/warnings/markings may be required. A classic example of an AD requiring additional markings is the yellow marking on many Beech Bonanza fuel gauges, denoting the last 13 gallons of usable fuel. If there’s only 13 gallons in each tank, takeoffs may not be legal.

Stuff You Don’t Have To Carry

The list of paperwork items you don’t have to carry aboard the aircraft is a lot shorter than the list of required items. Some examples include:

Maintenance Records

The aircraft’s logbooks, STC documentation and other maintenance records usually don’t have to be carried aboard the aircraft. They need to be produced if/when the FAA formally requests to review them, however. Instead, keep them in a safe place.

Pilot Training/Currency Records

Most pilots don’t need to carry their logbooks or training records. One exception involves student pilots, who need to carry their logbooks and endorsements for cross-countries.

Jeb Burnside is this magazine’s editor-in-chief. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.