When you think about it, the IFR system is really a wondrous thing. For example, every airport, navaid, fix and procedure has certain basic characteristics shared by all other similar facilities. For another example, a unique name or identifier is assigned, helping eliminate confusion between ATC and pilots. To navigate from one to another, the operator requests a route, naming the various facilities to be used. A flight plan is filed, or a radio request is made, a controller compares the request to his or her needs and a clearance is issued.

288

On one level, its a simple system. On another, its incredibly complex. So complex, in fact, errors are found every day by pilots and controllers, and then corrected. The result is a relatively safe and efficient national airspace system. One of the keys to making it all work, however, is pilots and controllers cross-checking each others work. Most of the time, no errors are found. Sometimes, though, someone forgets something, or the system proves too inflexible. In those situations, operators and ATC sit down to figure out what went wrong and develop procedures to consider each others needs. This is my tale of finding an omission in the system, and how little effort it took for a fix to be implemented.

In The Can

Over the past several years many consolidations have been taking place in the services provided to pilots by the FAA. The recent Flight Service Station “improvements” are perhaps best-known-certainly the most widely cussed and discussed-of these. However, long before the FSS consolidation took place, ATC went through a consolidation of its own and, while perhaps not as visible to the average pilot, there have been some rough spots there as well.

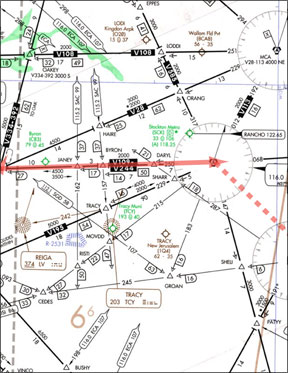

In the San Francisco Bay Area, there used to be several separate approach facilities. Sacramento, Stockton, Monterey and Bay were approach names familiar to many. They were merged under the moniker “Norcal” and the transition of services was supposed to be transparent to the pilot. Similar consolidations have been performed in the Washington/Baltimore/Richmond airspace, with Potomac Tracon the result.

More recently, there have been shifts between who gives the clearance to the pilot: Of course, the clearance always comes from ground or clearance delivery but some of them are standard and delivered by the tower controller directly, and others come from approach control and are passed through the tower controller. “Canned clearances” are becoming more common as a way to increase efficiency.

288

Sounds like a great idea, right? In the Los Angeles area, they have been using canned, or tower en route, clearances for years. Tower en route clearances, or TEC, were made a household term among pilots and ATC in the aftermath of the 1981 PATCO strike, when there simply werent enough controllers to go around. Basically, a flight using a TEC is an IFR operation from one point to another wholly within approach control airspace. In other words, whether by remaining at a relatively low altitude, by restricted routing or both, the flight is conducted outside the en route airspace structure normally the province of air route traffic control centers, or ARTCCs.

According to the Airport/Facility Directory (A/FD), “All published TEC routes are designed to avoid en route airspace and the majority are within radar coverage.” These days, TECs are published in advance-look in the back of an A/FD-and should be well-known to pilots.

Yet, for reasons known only to the FAA administrator, the TEC routes in the Bay Area are highly classified and are not available ahead of time to pilots. Even for short hops, you need to file a flight plan and work through the system TEC was designed to avoid.

Sometimes, you can get a tower en route from a controller up north but if you do, go buy a lottery ticket that very same day. The usual response is, “You need to call Flight Service.” The unfortunate consequence of this approach is that the canned clearances pilots receive can sometimes get you nicely from point A with absolutely no way to get to point B. By not publishing these canned clearances, they are not subject to real-world vetting. And therein lies the problem.

Quick Review

Before we go too much further, lets do a quick review of IFR communications failure procedures for your route. Remember, AVE-F? In the event of a communications failure, you are to proceed “By the route Assigned in the last ATC clearance received. If being radar Vectored, by the direct route from the point of radio failure to the fix, route or airway specified in the vector clearance.” If you cannot do either of those, you fly what you have been told to Expect and if absence of all of those, what you have Filed on your flight plan.

But, you, the pilot-in-command, are responsible for ensuring that when you receive a clearance from ATC, you can actually fly the clearance to your intended destination. We tend to presume, in this computerized age, that the clearances that we receive are good and that they will always get us to our destination. Would that it were so.

The System Falls Down

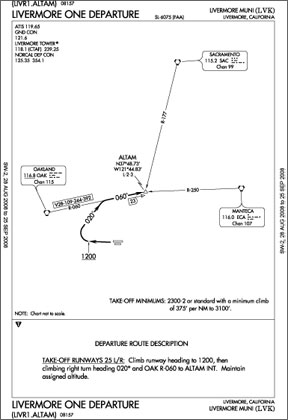

Recently, I set out on an IFR flight from the Livermore Municipal Airport (LVK) to the Castle Airport (MER) in Merced, Calif. The route clearance (which I found out later was a canned clearance) received was: “Cleared to Castle, Livermore 1 departure, Altam transition, Manteca, direct.” Since I had not flown there before, I had carefully reviewed the approach plates into Castle and knew Manteca was not on any of them.

I asked the ground controller for clarification as to what route to fly between Manteca and MER in the event of communications failure. I was told, “That is our standard clearance and it should be fine. They will probably just radar vector you, anyway.” Even the tower controller was presuming the “canned” clearance must be correct.

“No,” I pushed back. “There is no way to get to the IAF at Castle from Manteca. I have a hunch that in the event of lost comm, Norcal would not want me wandering around out there on my own but would rather give me a clearance I can fly. I cant accept this since I cant get to Castle with it.” There was a very long silence (fortunately, the airport was not busy as it was still early in the morning).

The ground controller was totally unprepared for my question and eventually responded they would call Norcal and get clarification. Oddly, what came back was, “Well, if you lost comm, what Norcal wants you to do is to go direct to Modesto VOR and then direct to the El Nido VOR”. Okay; now I had something that made sense and I could fly in the event of lost communications. I asked for and received a phone number for Norcal and resolved to call them upon my return.

Follow-Up

Upon my return that afternoon, I called the supervisor at Norcal. He explained they had recently consolidated the responsibility for delivering approach clearances and there were literally hundreds of them needing to be checked. I went over the clearance I had been given and he agreed it didnt sound right. He wanted to do more research and would call me back.

When he returned the call, he verified the error. The clearance should have been “Cleared to Castle, Livermore 1 departure, Altam Transition, Manteca, direct El Nido, direct.” He also told me that there were several others needing correction and he would be submitting a “fix-it” request.

In the example above, and based on the IFR-approved GPS equipment suffix stated in our flight plan (/G), we could have navigated to any number of IAFs on any number of approaches. But since there was no published transition to get to one from Manteca, we would have had to go direct and navigate on our own. Remember the original clearance limit was Manteca VOR. That would have been interesting-off-airway navigation direct to any one of several IAFs on any one of four different published approaches.

When I discussed that possibility with the supervisor, I got a combination laugh and groan, accompanied by, “Please, lets not let that happen. Lets make sure you get a good clearance in the first place so you have something solid to fly in the event of lost comm.” Clearly, ATC would prefer you fly a valid route clearance they have given you rather than going direct based on a combination of a poor clearance and original flight plan.

Lessons Learned

There are a several key lessons here. You should never accept a clearance that does not get you to a fix from which you can begin the approach. That means either an IAF or some other fix on the published approach providing a distance, heading and altitude to fly. If you dont get that in a clearance, dont accept it or, at the very least, ask for clarification of lost communications procedures. Cross-country flights dont seem to be affected as much by this but in the local Norcal area, some disconnects have developed, involving Livermore and several other airports.

The second lesson is that once you encounter an issue like this, work to improve the system for the next guy or gal. Get a phone number, talk to ATC. These people are real pros and they do not want bad clearances floating around the system any more than we do. They want all the bases covered as well so that if the lost communications procedure becomes necessary, its executed smoothly and with a minimum of disruption.

Phil Blank holds Airline Transport, Flight Engineer and Flight Instructor certificates. He is type-rated in several jets.