Fortunately for those of us who fly, runway incursions that cause accidents are relatively rare. But thats not to say incursions themselves are rare: Runway blunders have become an everyday thing, so much so that NASAs Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) has thousands of incident reports best described as coulda-beens. We recently reviewed an intriguing report on this subject delivered to the 288 International Symposium on Aviation Psychology in Dayton, Ohio, last April by Dr. Ed Wischmeyer, an aviation researcher and contributor to our sister publication,

Wischmeyer says his research is less a statistical study and more a snapshot of why crews say incursions happen: “There are undoubtedly classification errors in this analysis as the tabulation was so mind numbing as to make consistency difficult.” Its purpose was to identify significant incursion factors, not to generate statistically significant tallies. Those factors are both numerous and worrying.

Incursion Categories

Wischmyers research broke incursion and taxi incidents into five major areas: Flight crew factors, controller factors, information factors (charts, Notams and the like), communications factors and airport factors. When all the possibilities are considered, it almost seems as if theres a conspiracy to lure pilots down a taxiway or onto a runway where they dont belong.

One of most surprising findings was how controllers have one expectation while pilots have another. As the comments from former OHare International tower controller Denny Cunningham demonstrate in the sidebar opposite, sometimes the conceptual divide is large enough to drive an airliner through.

Topping the list is that crews will be able to see and follow all signs and markings, something any of us whove flown at night or at strange airports know isnt realistic. Copying and executing clearances is another thing controllers expect pilots to do, but controllers dont realize how difficult it is for pilots to do this on the roll, either after landing or on the way to runway. This came up in a number of reports.

Before a ground or tower controller is certified on position, he or she has to know the airport layout cold. This means controllers assume pilots know it, too, and will take a specific taxiway without being told or theyll expedite across taxiways and runways to suit the controllers separation plans. Controllers sometimes count on pilots to do this, even without specific instructions.

In turn, the reports indicate controllers have an imperfect understanding of aborts and go-arounds. Controllers assume a crew can abort a takeoff at any point or execute a go-around at any point or, conversely, that a crew wont initiate a go-around unannounced. This has implications for required runway separation and more than one controller has been surprised when the pilot-who was entirely in the right-didnt do what the controller expected.

Another general assumption by ATC, according to some reports, is that pilots know all about conditions and/or unique procedures at an airport without any additional coaching from ATC. Controllers often dont realize this information is buried in Notams or the

Airport/Facility Directory, if it can be found at all. An announcement or two on a long-winded ATIS isnt enough.Two-Way Street

If controllers lack knowledge of cockpit considerations, pilots have their own set of assumptions that dont match reality. For instance, pilots expect hold short lines will be near runway ends; many are not. They may also assume if theres an ILS hold line, a runway hold line will be beyond it, yet this isnt consistent from airport to airport.

For pilots, the Holy Grail of training is standardization; were taught that safety margins accrue by doing everything the same way every time. Yet because of lack of signage, poor taxiway design, non-standard ATC procedures and a host of unpredictable variables, strict standardization doesnt always work when taxiing. One observation in the report is pilots expect a taxiway sign to support every turn in a taxiway clearance, something rarely true.

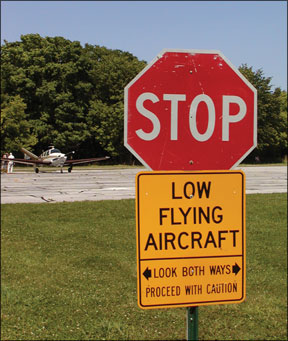

Non-towered airports present a separate set of challenges. Pilots intuitively know Unicom announcements are iffy at best, yet they often operate as though all transmissions from their own aircraft will be heard by all other pilots. They further assume no matter how short a time an aircraft has been on frequency, its been long enough to have heard all of the relevant transmissions.

Although we all know better, the ASRS reports suggest that pilots often use radio transmissions as an all-purpose crutch, assuming received transmissions from other aircraft make looking for traffic optional or turning on lights and making radio calls eliminates the need to look.

Its surprising how often pilots are caught unawares by another aircraft flying a non-standard approach or the wrong pattern, but the reports indicate this is the case. Another assumption-probably by the pilots flying these non-standard procedures-is that everyone in the pattern will see and accommodate an airplane approaching from where its not expected.

Airport Design

The people who design, build and maintain taxiways have their own blindspots. For example, they assume hold short lines will always be seen and observed regardless of its location relative to the runway end. They further assume all markings will be visible from both seats of a taxiing aircraft, even a taildragger, regardless of their location and illumination. Similarly, they expect pilots to accommodate non-standard construction signs and markings.

Hold-short lines in unexpected places were a common problem, according to Wischmeyers research, with 35 events noted. The data suggest pilots may not start looking for hold short lines until cued by the end of the runway, after which it may be too late. There were also cases of single hold-short lines serving multiple runways, no hold-short line past an ILS-critical-area line and one report of a hold-short line with its dashed and solid sections reversed.

One interesting phenomenon emergign in the reports is what Wischmeyer calls the “greater-than-90-degree-turn” problem. It appears pilots associate the word “turn” with a turn of 90 degrees or less. And although English has verbs for proceed, zig and veer, it doesnt have a word to describe turning more than 90 degrees. There were 11 reports involving turns greater than 90 degrees, nine of these from turbine and jet operators.

Also noted were eight instances where the flight crew had difficulty or couldnt find a designated taxiway on the chart because of arbitrary taxiway naming schemes. One reporter observed inner and outer loops were not labeled consistently at different airports, suggesting letters and numerals alone may not always suffice. There were numerous cases of inadequately marked runway and taxiway closures and where poor markings caused confusion.

Radio Rage

A major surprise in the data was the number controllers either berating or deliberately delaying flight crews following a perceived error. There were 43 such events, of which seven contributed to a further problem.

The data showed low-end operators receiving such treatment-1.8 times more frequently than high-end operators-supporting the perceived notion that a pilot whos hesitant or timid on the frequency wont be received warmly. In a similar study five years ago, such events were unheard of. There were also 12 cases of controller unintelligibility (at U.S. airports) due to poor enunciation or too-rapid speech.

Clearance confusion and misunderstanding also came up as incursion causes. In eight cases, the flight crew parroted an instruction and then did something else. Only three of these were from low-end operators. Its significant that reading back transmissions is the first-line defense against communications errors. However, four percent of the reports Wischmeyer reviewed described frequency congestion or busy controllers, situations compromising this counter check.

Four per cent of the reports (39) related to confusion between “hold position,” “hold short,” “position and hold,” and even takeoff clearances, with similar rates from both high- and low-end operators. A careful reading of the reports suggest, although these directives intend entirely different actions, they all use the same or similar words.

To a degree, all of us might fairly assume both controllers and pilots share a common understanding of how to determine the active runway. However, theres nothing in the FARs or the

Aeronautical Information Manual on how to do this. It reminds us of the scene in A Few Good Men where all the Marines just automatically know where the mess hall is. Some controllers said they regarded all runways as “active” and not to be crossed without a clearance, which is inconsistent with the AIMs explanation of how taxi clearances are supposed to work.Conclusions, Observations

For us, Wischmeyers paper revealed a system with troubling shortcomings-if indeed we can even call what we have now a system. Much of the taxiway design and procedure methodology seems to have evolved in isolation from the purpose of the whole-theres little obvious coherent design, never mind lucid coordination between physical and human components.

One wide-body captain wrote after a near-collision at San Francisco, “We (the industry) could do better about airing solutions as well as hammering into the crews that we have a problem.” The ASRS reports indicate that theres plenty of blame to go around.

If we read Dr. Wischmeyers conclusions correctly, meaningful improvements wont come from ATC working on terminology in isolation, nor by a review of signage and markings in isolation, nor by recommendations for new procedures and rules. In that sense, spending millions on ground radar is a band-aid solution applied to a patient in need of a heart transplant.

Systems engineering and safety science long ago proved that meaningful improvements come only when each component of a system is reviewed and improved within the context of the entire system. Its pointless to apply a rigid standard to taxiway signage if controllers arent aware of what the pilots are seeing from the cockpit and tailor their clearances to suit. Furthermore, they have to be flexible enough to adjust to temporary changes on the airport-such as construction or snow removal-and to realize they must advise pilots accordingly. Training has to be uniform so controllers do this consistently from one airport to the next.

Flight crews-both private and commercial-and the companies employing them may have to live with some givebacks in terms of cherished procedures. For example, one reporter said this: “Company procedure is to get our weight and balance data during taxiing. Doing this prior to taxi would be a means of reducing distractions during taxi.”

Our impression from reading Wischmeyers paper is the FAA wont be able to intrude into the cockpit-or perhaps even the tower-enough to make such system-wide improvements stick. What will ultimately make runway incursions the rarity they ought to be is an industry-wide commitment to both acknowledge the problem and fix it with system-based solutions.

just read this report, I was an air traffic controller for 40 years, majority at o’hare, have a BA in psychology and never never verve assumed pilots were familiar with the airport. no good controller would assume!