The date was July 15, 2008. The private pilot had almost 1000 hours total time, and 44 in the TBM 700 accident aircraft. The airplane was landing at Cobb County International Airport-McCollum Field on Runway 9, elevation 1078 feet msl and more than 6300 feet long. It was on final approach to the runway in daytime visual conditions reported as 5500 feet broken with 10 miles visibility. The wind was from 120 degrees at six knots.

According to the NTSB, ATC instructed the pilot to perform one “S” turn, then another three miles from the runway, for spacing. During the second maneuver, ATC advised the pilot he could turn onto his final approach. In response, the pilot banked the airplane sharply to the left. Witnesses stated “the airplane seemed to do a wing over onto its back and go straight down.” The airplane was destroyed by impact forces and a post-crash fire. The solo instrument-rated private pilot (male, 66) was fatally injured.

In the investigation of this accident, toxicology testing revealed multiple medications were present, including a drug for benign prostatic hypertrophy (enlargement of the prostate gland), a blood-pressure medicine, a cholesterol-lowering medication, the drug quinine that is often used for nighttime leg cramps and the analgesic Tramadol. Only the blood-pressure and cholesterol-lowering medications had been reported to the pilot’s AME and the FAA on the most recent aviation medical examination. The NTSB noted, “It is unclear what role, if any, the medication or the condition for which it might have been used played in the accident.”

FAA ACCIDENT DATA

This accident illustrates some of the findings reported by the General Aviation Joint Steering Committee (GAJSC) and their Loss of Control Work Group that studied approach-to-landing accidents about 10 years ago. They focused, in part, on flying and medications as well as drug/medication combinations. A drug is a prescribed medication that is given by a medical provider; a medication is a substance that we can buy in a grocery store or pharmacy without a prescription.

An additional report from the FAA reviewed fatal aviation accidents occurring between 2004 and 2008. Of the 1353 pilots who were fatally injured in these crashes, more than 40 percent tested positive for medications or drugs. Ninety percent of the deceased pilots were flying in Part 91 operations. The extent of the impairment from the drugs and medications could not be fully determined with the toxicology studies that were done, but the FAA said it was “a cause for concern.”

IMPAIRMENTS

Most of the drugs and medications found in the toxicology reports from fatal accidents carry specific warnings against operating machinery or motor vehicles, including aircraft, or performing tasks that require alertness. Notably, illicit drugs always impair human performance. It is also likely that health care providers may prescribe drugs that could compromise a pilot’s abilities if the physician or provider is not aware that the patient is a pilot.

Pilots may themselves not be aware of the presence of sedating antihistamines comprising many over-the-counter treatments for allergies, coughs, colds or sleep aids, and they may not discuss the side-effects of prescription medications with their treating doctor. In addition to the sedative effects from many medications, another significant concern is impairment of a pilot’s cognitive ability, including subtle degradation of the ability to evaluate competently actual impairment should it occur. A pilot’s underlying symptoms (e.g., head congestion, runny nose, cough, nausea, anxiety, muscle spasm, insomnia or pain) can be reduced by medications but at a significant cost of unrecognized slowing of thought processes that impair the safety of flight.

The FAA has noted it is not always easy to determine the extent of impairment that may have contributed to a fatality because different medications affect different pilots to varying degrees. In the toxicology studies from fatal accidents, the investigators do not always know about the pilot’s health at the time of the accident or what pre-existing medical conditions may have been present that required the medications found in the toxicology reports. After an accident killing the pilot, it often is not known whether an AME was consulted about using the drugs or medications present, and drug-drug or drug-medication interactions are seldom investigated. These findings leave us with a quandary regarding federal drug labeling standards and whether they are intended to provide information for patients, for health care professionals or both.

Combinations of prescription and over-the-counter medications can be particularly dangerous. Pilots are encouraged to consult their personal physician or their AME before taking a combination of medications. Combining two or more prescription medications may not be known to either the prescribing provider (usually a personal physician) or to the AME.

Importantly, many hospital and retail pharmacists have computer programs that can estimate possible drug/drug or drug/medication interactions. If there are questions, these resources should be consulted.

Finally, pilots must truthfully report all their medical conditions and their drug and medication use on their medical application forms and, as noted, should consult their AME with respect to any medical conditions and drug use before flying.

MEDICAL DEFICIENCIES

Meanwhile, federal aviation regulations are rather specific about pilots not exercising their privileges during periods of medical deficiency. A primary question that we then need to address is, “What constitutes a medical deficiency?” The FAA says that any medical condition that would make a person unable to meet the requirements of the medical certificate that is necessary for that pilot operation constitutes a medical deficiency. In addition, FAA notes that if a pilot is taking a medication or receiving other treatment for a medical condition that results in the person being unable to meet the requirements for the medical certificate, that situation also constitutes a medical deficiency.

Instructors need to advise students that before every flight, every pilot should ask themselves, “Do I have a medical deficiency that precludes safety?” If there is doubt, they should consult their private physician to determine whether they have a deficiency that would interfere with the safe performance of their piloting duties.

These stipulations are covered in FAR 61.53, which prohibits all pilots—both those required to hold an airman certificate and those who are not—from exercising the privileges of their certificates during periods of medical deficiency. The revised FAR 61.53 includes sport pilots who use a current and valid U.S. driver’s license as their medical qualification. In other words, all pilots with private, commercial, ATP or sport pilot certificates are required either to have their medical deficiency cleared, or they need to self-evaluate their medical deficiency and any limitations it would impose on conducting the privileges of their pilot certificates. Importantly, this prohibition is added in FARs 61.23 and 61.303 for sport pilot operations.

The FAA’s FAR 61.23 (c)(1) says that a person must hold and possess either an FAA medical certificate or a U.S. driver’s license when exercising the privileges of a sport pilot certificate in a light-sport aircraft. The FAR notes that a person using a driver’s license to meet the requirements of paragraph (c) when operating under the conditions and limitations of FAR 61.113 (private pilots) must meet the requirements listed there. The pilot also must comply with the medical requirements associated with the driver’s license.

In addition, since July 2006, they must have a medical certificate issued under FAR Part 67 and complete the medical education course that is set out in FAR 68.3 during the 24 months before acting as a pilot in command, and they must receive a comprehensive medical examination from a state-licensed physician during the 48 months before acting as pilot in command. These are the well-known requirements for Basic Med.

Prior to 2020, the FAA did not have an easily accessible list of medications on the “do not fly” list for pilots. Federal Air Surgeon Dr. Michael Berry announced in the January/February 2020 issue of FAA Safety Briefing that such a list would be made available. The result, a PDF document titled, “What Over-the-Counter (OTC) medications can I take and still be safe to fly?” is a free download from the agency’s web site: tinyurl.com/SAF-Meds.

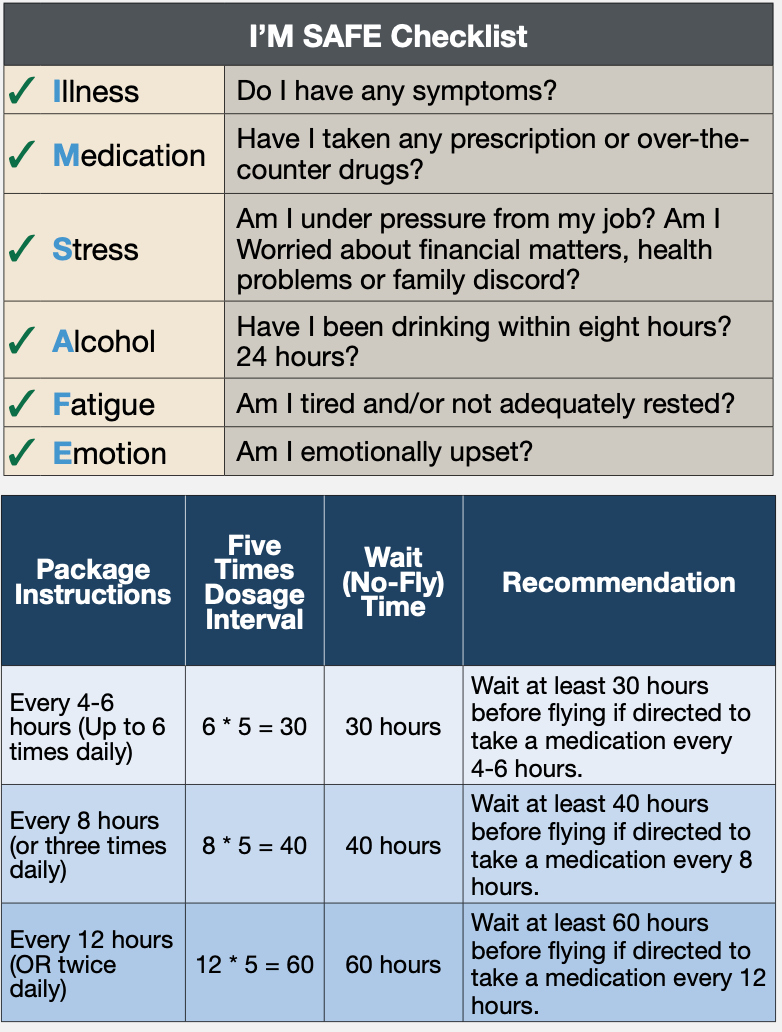

The list, along with the I’M SAFE checklist, reproduced at top right, should be used by all pilots and flight instructors before every flight. The document includes a checklist of questions that specifically targets over-the-counter medications, indicating whether a pilot is safe to fly when using them. The symptoms on this checklist are easily recognizable, and this checklist should be completed prior to a flight by any pilot taking over-the-counter medications.

The document also reviews different and common medications and lists products where the medication is commonly found, whether the medication or its active ingredient is generally safe for flight, whether these medications or their ingredients should be avoided and the rationale supporting the recommendations. It also includes information on when pilots can fly after stopping to take a medication, reproduced at bottom right. These guidelines are written in plain language and can help pilots determine whether it is safe to fly while taking over-the-counter medications.

DRUG/MEDICATION LABELING

Recently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) changed the labeling on over-the-counter medications. Instructors should urge all pilots and learners to read the label on over-the-counter medications. These new FDA-directed labeling standards are written for the medication user and are specified in non-technical, non-medical language. The over-the-counter medication labeling now includes, by statute, the active ingredients in the medication, the purpose of the medication and its uses, along with warnings about adverse effects that may occur when using the it. The labeling also includes specific directions for the use of the medication.

Among the greatest offenders for producing side effects in all of us—but particularly in pilots and flight instructors—are sleep aids and cough medications. Both these medications likely contain antihistamines that may cause either drowsiness or sedation, and their so-called hangover effect may last several days. These drugs are intended for short-term use only, and while they are being used, pilots and instructors should not fly.

How long must a pilot wait after taking potentially sedating or performance-impairing medications before initiating a flight? The FAA is very specific about how long we should wait and recommends waiting five times the dosage interval for the medication. The dosage interval is the number of hours between doses as prescribed. For example, if the drug is taken four times a day (every six hours is then the dosing interval), five times that dosing interval is 30 hours. The second table on the opposite page goes into greater detail.

Aviation Medical Examiners (AMEs) and the flying public can access the FAA’s Guide for Aviation Medical Examiners on the agency’s web site: tinyurl.com/SAF-AME. The site includes a list of pharmaceuticals (therapeutic medications) which are illegal to use while serving as a pilot and listed as “Do not issue, Do not fly.”

A brochure about medications and flying from the Civil Aerospace Medical Institute is also available as a PDF at: tinyurl.com/SAF-Drug. These publications provide background guidance and information that should be discussed with an AME or a pilot’s personal physician to clarify whether it is safe to fly while using the prescribed drug.

PRESCRIPTION DRUGS

What about taking prescription drugs? Prescription drug labeling (the FDA-mandated package insert) is directed to health care providers in very technical language that the consumer may find difficult to understand or may not have access to at all. It is written in very small print and contains technical language that may not be understandable to a layperson. Importantly, many prescription medications carry a recommendation not to operate a motor vehicle or hazardous machinery including cars, airplanes, boats and other motorized equipment while taking the medication. An additional source of complexity is that prescription medications are often prescribed individually but may be prescribed by different health care providers who are unaware of all the patient’s other medications. Again, potential drug-drug interactions may either be unknown or not addressed.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The FAA recommends consulting an AME before flying when using either prescription or over-the-counter drugs. It encourages all of us to make sure the AME knows about all the drugs we are taking. We are also to tell our personal physicians and prescribing doctors that we are pilots and to inquire about adverse effects of prescription medications and drug combinations. Finally, between medical provider visits, we are reminded that we are self-assessing our physical and mental condition before each flight. We are to ground ourselves when we determine that we are not fit to fly.

Dr. Victor Vogel is a Pennsylvania-based physician and Cirrus SR22 owner. He’s also a flight instructor with an instrument-airplane rating.