If there’s any upside to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic—any at all—it may be that many aircraft cockpits are cleaner than they’ve ever been. As a direct result of the pandemic and related guidance from public health officials, it’s not a stretch to suggest that crewed, rental and fleet aircraft of all sizes and types are regularly undergoing disinfection procedures more often than ever before. Generally, that’s a good thing, of course, and something that makes us wonder what these cockpits harbored for their occupants before 2020.

Just as with so many procedures involving aircraft operations, there’s a right way and a wrong way to disinfect an aircraft cockpit. Since the pandemic, many aircraft and avionics manufacturers have published specific guidance for owners and operators looking for information on disinfectants and other chemicals, and their interaction with the aircraft and its equipment. One resource is an online list maintained by the General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA), with links to related information from airframe and avionics makers. That list may be retrieved from GAMA’s web site at tinyurl.com/SAF-GAMA.

The FAA on November 4, 2020, meanwhile, published guidance—Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO) 20009—which cancels and replaces SAFO 20003 and provides what the agency says is “updated interim occupational health and safety guidance by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for air carriers and crewmembers.” The new SAFO includes an appendix providing guidance for U.S.-based crews and those based elsewhere while they’re in the U.S. It cautions that “disinfectants used should be compatible with the aircraft and approved by the aircraft manufacturer for use on board the aircraft.”

The FAA also on November 4 released Special Airworthiness Information Bulletin (SAIB) NM-20-17, “Aircraft Interior Disinfection.” The new SAIB “focuses on the potential near term and long term implications for airworthiness, and is directed to all persons responsible for airworthiness,” the FAA said, adding, “Although disinfection is not directly related to aircraft airworthiness, too frequent or improper application could result in negative impacts.” Those “negative impacts” could include corrosion, embrittlement, increased flammability and/or electrical short circuits. “Depending on the system or part affected, any of these conditions could create either an immediate or latent airworthiness issue,” the SAIB states.

The FAA’s new SAIB also states that the agency does not treat disinfection practices as “maintenance” under the FARs “because disinfection is not necessary for the airworthiness of a part or system” and “such practices have not been addressed in the instructions for continued airworthiness” in its aircraft certification rules. “Although the selection and use of improper chemicals and cleaning methods could damage the aircraft and affect its airworthiness, that possibility, in and of itself, does not make the activity maintenance or preventive maintenance. It follows that disinfection is also not maintenance,” the FAA’s SAIB states in a footnote.

One of the punchlines here is that anyone can perform disinfection tasks; they don’t have to be a certificated technician.

The SAIB also includes a series of recommendations to help ensure continued airworthiness. For example, the SAIB cautions that, “In general, fogging and misting allow the ingress of disinfectant into areas where disinfectants are not intended to be used (e.g., underlying structure, fan cooled electronic boxes, smoke detectors). Running aircraft ventilation will typically exacerbate this condition.”

Additional guidance includes, “Avoid allowing liquids to pool, regardless of how they are delivered” and be “especially careful when using liquid disinfectants in the flight deck…. Liquids can intrude into flight deck switches and seals…[and] lead to electrical shorts in the near term and unexpected corrosion in the long term.” The SAIB also cautions that “alcohol based disinfectants can cause crazing on windows and window dust covers, and can damage thermoplastics,” which may require replacing the components.

To ensure the cleaning and disinfecting products used on your aircraft meet the appropriate recommendations, review the online GAMA list mentioned earlier in this item and/or contact the manufacturer directly. The FAA’s new SAIB on aircraft interior disinfection is available as a PDF at tinyurl.com/SAF-ICA.

FAA Isn’t Implementing New FAR 23, Says GAO

A new report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) says the FAA’s revised FAR Part 23 regulations, which went into effect in 2017 and implemented new performance-based certification standards for small airplanes, “specify required results but do not prescribe any specific method for achieving” them. “For example, FAA staff who perform design reviews expressed uncertainty about the level of detail that applicants need to provide when showing how their designs meet the new regulations,” the auditing agency said. According to FAA staff and GAO’s review, “this and other challenges are partly due to a lack of guidance on how to address issues created by this new approach.”

The FAA’s FAR Part 23 rewrite stems from legislation enacted in 2013, the Small Airplane Revitalization Act. It required that the FAA streamline its small-airplane certification process to improve safety, reduce the regulatory burden, and spur innovation and technology. A new FAR Part 23 was issued in December 2016 and introduced so-called “performance-based regulations.” Ironically, it’s the FAA’s performance that was found lacking by the GAO, which says the agency has not “developed performance measures for the revised regulations or a plan to develop such measures.” “FAA officials stated that they have not been directed to develop performance measures specific to the implementation of performance-based regulations for small airplanes and do not have a plan to do so,” the GAO said. “Without performance measures, FAA will face difficulties in determining the effects of the revised regulations,” the auditing agency added.

New ADs On Cracking, Corrosion In Cessnas And Cherokees

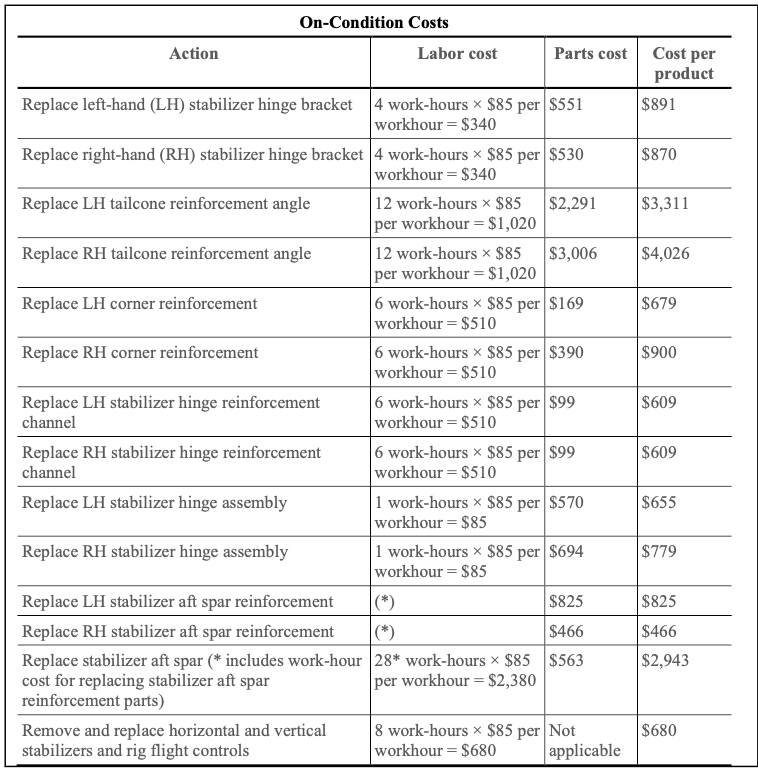

Two new airworthiness directives (ADs) slated to go into effect in December focus on finding and addressing cracks and corrosion in several thousand popular Cessna and Piper airplanes. The first of the new ADs to go into effect targets some 6500 Cessna 180, 182 and 185 airplanes on the U.S. registry. The FAA is mandating inspection of these airplanes to “detect and correct corrosion and cracks in the tailcone and horizontal stabilizer attachment structure.” The second AD focuses on more than 11,000 U.S.-registered Piper PA-28 and PA-32 models with non-tapered or so-called “Hershey Bar” wings, and calls for inspections of the wings’ main spars. Both ADs also require recurring inspections.

The AD targeting Cessna 180 through 180K, 182 through 182D, and 185 through A185F airplanes was “prompted by a report of cracks found in the tailcone and horizontal stabilizer attachment structure,” according to the FAA. It requires inspecting those components for corrosion and cracks, and repairing or replacing damaged parts “as necessary.” The AD became effective on December 7, 2020, and the required inspections, described in greater detail by Textron Aviation Single Engine Mandatory Service Letter SEL–55–01, are to be accomplished within the next 12 months, then again every five years or 500 hours in service, whichever occurs first.

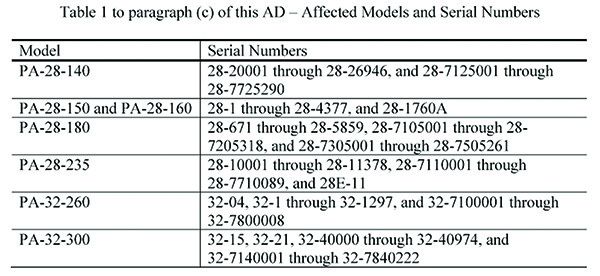

The Piper AD, meanwhile, seems to include all fixed-gear, “Hershey Bar”-wing PA-28 Cherokees and PA-32 Cherokee Six models. The table at the bottom of the opposite page lists the affected models and serial number ranges. Like the Cessna AD discussed above, the Piper action stems from field reports, this time of corrosion found in an inaccessible area of the main wing spar. The AD is designed “to detect and correct corrosion in the wing root area of the left and the right main wing spars,” the FAA said. Access panels may need to be installed for the inspection, and the AD references manufacturer instructions for installing them.

If corrosion is found during the required inspections, it must be removed and the thickness of the remaining material assessed as described by Piper Service Bulletin No. 1304A. If the material’s thickness is less than the specified minimum, it must be repaired before further flight. The Piper AD was scheduled to become effective on December 28, 2020, and the inspections it requires are to be performed within the next 100 hours or 12 months, whichever occurs first. Recurrent inspections are to be performed no less often than every seven years.

The Cessna 180/182/185 AD is AD 2020–21–22; the one for listed Piper models is AD 2020–24–05.