Referring to your September 2008 article, “Batteries Not Required”-a nice review of cross-country basics-I have a question and two comments. The question refers to the flight log: Why is “1.2” in the logs Time box when the block time was 1+35 or 1.6?

One comment involves missing a possible teaching opportunity by not discussing MOAs, the planned route and altitude, and the floor of the Lemoore C MOA.

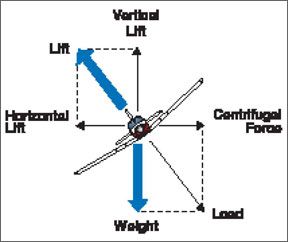

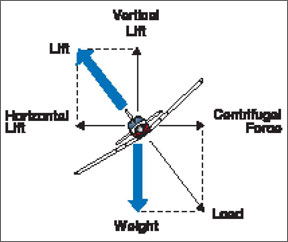

The other comment involves the sidebar, “Lifts Horizontal Component,” which discusses steep turns and includes a quote from an FAA publication on the need to create additional lift in a turn. You then add your conclusion that “Increasing angle of attack, of course, increases the stall speed.”

This is not the message I would want my students to gain from your article. Your statement is not true in the commonly practiced stall entries from 1G straight and level flight. There the increasing angle of attack doesnt “increase” stall speed.

288

In truth, even in the situation under discussion-stalls while turning-it is the increased load factor that increases the stall speed.

It can be argued that increasing angle of attack does often increase load factor (pull ups, turns, etc.) but wouldnt it be preferable to instead conclude that stall speed increases as a result of increasing load factor? That is a true statement always.

Jaime Alexander

Via e-mail

Author Phil Blank responds: “Good catch. Due to all the scribbles, notes and folds, the original log sheet from the flight could not be used for publication. It was manually copied by hand and somehow this typo (or write-o) snuck in.

“As far as the MOAs are concerned, during the writing of the article we considered including it. Since this was an article that was focused on navigation (as opposed to airspace), we elected not to include it. Perhaps we should have made this a two-parter since there were other items that we wanted to include as well, but maybe an airspace article will be in the pipeline now.

“Thanks for taking the time to respond.”

Regarding the sidebar and discussion of angle of attack, load factor and turns, youre right, of course. That material was added during the editing process by someone whos spent way too much time at altitude without supplemental oxygen.

Ditching Dos and Donts

Walter Atkinsons August 2008 article, “Mitigating Terrain Risks,” contained excellent advice, but I have to differ with the characterization of “water” as “dangerous” terrain. Every flight in my Bonanza here in Hawaii is an overwater flight. Unless its a nasty day on the surface, I would rather take my chances in the ocean, versus mountainous or other hazardous ground landing options.

288

For example, one thing youre not going to have in the water is a fire. So, unless you do your flying around Kansas or the Mojave Desert, you might consider water as a great alternative landing site. Any water is a more consistent surface than much of the earth. The key, as Walter describes, is in preparation, both mental and equipment. Here are some things he didnt mention:

Always wear your life jacket (pax too!). In a ditching, you will probably get out with what you have on.

Have your overboard gear properly stowed for ditching. If you are alone, it is strapped in the right seat, ready to deploy. Visualize how to deploy and use it.

Have a raft and a watertight ditching bag. Put in everything the Coast Guard recommends, plus a PLB. Cheap pair of glasses? Bottle of water?

Put a radio in its own waterproof bag in your ditching kit, with its batteries in a separate waterproof container. Write the emergency frequencies on the radio.

If you are in the water with your life jacket inflated and have trouble getting in the raft, take the jacket off or deflate it (once you have a hand hold).

Always be on the radio with flight following. If you get out of radar range, call in your position every so often until they pick you up again.

Plan to be quickly vertical, then inverted. Practice the hand and foot movements to get out. Brief your pax completely so they help, not hinder (you could be unconscious).

Remember the relative position of any boat/ship you pass near. You will want to land as close to them as possible.

Practice reading the surface of the water for swell and wind directions. Read up on ditching technique and visualize how you would do it.

Mentally keep track of how far you can glide from your various altitudes.

288

On this last point, I would say to Walter, “Go back to flying direct to Key West.” If you are at 9000 feet, you can glide maybe nine miles. That means the only time going via Cross City helps you at all is when you are within a nine-mile radius (less, once youve passed it).

So, you are adding 20 minutes to your flight under the assumption you are going to have an emergency during the few minutes you are close enough to Cross City to make any difference. This would be a truly remarkable happenstance, given the probability of an emergency and the number of hours flown.

To me, the probability of an emergency over trees, mountains or an urban area are much higher, and the possibilities for a survivable landing much lower. Ditchings have a very high survival rate…if you are prepared.

Brian Barbata

Hawaii

Thanks for the feedback. As it happens, weve already scheduled an article for an upcoming issue by a writer who successfully ditched an airplane. The lessons learned from that event are worth repeating.

Unobtainium

Your August editorial on the trials and tribulations of maintaining an older aircraft hit home. I own and fly a 1966 Beechcraft Musketeer Model A23-19, IFR equipped, and step by step am getting involved as much as I can to learn about this plane: its characteristics, its equipment, its capabilities, its needs.

Owner involvement is essential! It is an irresponsible state of mind to think that pre-flights and annuals will suffice for the long-term health of the plane. It is too likely you will find long gaps between log book entries, changes made without entries, unauthorized equipment installed, required work not performed, and it is these voids in the care of the plane that will get you in trouble. The older plane owner should go into the project with the idea he has to perform “catch-up” maintenance and frequent flying.

Dick Williams

Via e-mail