I thoroughly enjoyed Dave Higdon’s article “Pitch? Or Power?” in the October issue. For years I argued vehemently against separating pitch and power.

A little background: I learned to fly in the USAF and was lucky enough to fly a lot of different stuff—helicopters, pistons and jets (/H). From a T-28 to a C-141 with the H-19, H-3, H-1 and T-38 in between. So I have experienced the “set the pitch on final and fly the throttles” as well as the helicopter thing, where all controls are jealous of each other and you must move them all together.

I think, however, that for a beginning student this is not helpful. I am not a highly experienced instructor of new students in piston airplanes. But I am convinced that pitch for airspeed and power for climb/descent is the easiest way for someone to learn to land an airplane. An exercise that I find works wonders is a simple, “You have the controls except the throttle, maintain X airspeed.” From slow flight to cruise, I get to move the throttle from idle to full while the student maintains the stated speed.

When I have used this approach to teaching, the student learns to nail the airspeed on final and that is the primary ingredient in consistent landings. It works especially well for wheel landings in a taildragger; maintain a reasonable speed a few feet above the ground, keep the airplane lined up, kill the drift and reduce power slightly. Successful landing every time.

288

So make this article the basis for 300-level or higher courses, and stick with Stick and Rudder for the 100-level stuff.

Ernie Betancourt

Via e-mail

The “Keep It Simple” school of thought on this stuff does have merit. But focusing on airspeed alone ignores other aspects of an aircraft’s performance. And we’re still coordinating pitch and power to obtain the desired performance. Why not teach this from the beginning?

It’s Not a Dry Heat

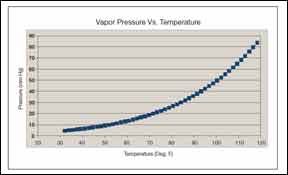

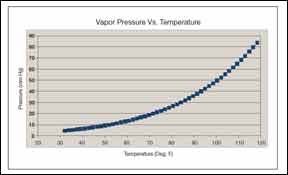

I read Scott Murray’s “Humidity Vs. Horsepower” article in the October issue with interest. I agree, but I tend to take a more simplistic view.

288

Hopefully, all pilots know that aircraft performance diminishes as air density decreases. Given that pressure and temperature remain constant, adding moisture to dry air decreases density, thereby diminishing performance.

For many people, the surprise may be that wet air is less dense than dry air. To understand this, we need to know a couple of molecular weights. The mixture of gasses that comprise dry air has an effective molecular weight of 28.97. Water has a molecular weight of 18.02. The takeaway here is that water vapor is lighter than dry air.

When water exists as vapor in air, its behavior is governed by its partial pressure; that is, the component of barometric pressure attributable to only the water vapor. This pressure value will be sufficiently low that the water vapor’s behavior will be well approximated by the ideal gas law. A mixture of dry air and water vapor may thus be analyzed as a mixture of two ideal gasses.

The ideal gas law tells us that if pressure and temperature are constant, then a fixed volume of air will always contain the same number of moles regardless of whether the air is dry or wet. If some of those moles are the lighter water vapor, the air will be less dense.

Simple as that!

Donald A. Moen

Via e-mail

Back To Ground School

I appreciate Amy Laboda’s recognition that she lacked knowledge of the earth’s magnetic anomalies and her statement that she never learned about this during private pilot training or through reading higher level textbooks. Although I currently work part-time as a CFI-I in the U.S., all my training occurred in Canada, and it was there in my private pilot ground school that I learned about such magnetic anomalies. This point emphasizes a great disparity between FAA (Part 61) and Transport Canada-approved training curriculums.

Formal ground school is required for all student pilots in Canada and I think this greatly improves their knowledge base. I require all my students in the U.S. to have an intensive curriculum of ground school lessons with a ground instructor or flight instructor, and this allows us to cover additional topics such as Amy’s recent revelation.

Textbooks do not cover enough of the basic material and that is why ground school is necessary to fill in those deficiencies. I believe that the current Part 61 training system does injustice to student pilots by not requiring a formal ground school. Adding ground school to Part 61 training may be a good starting point to producing more knowledgeable pilots.

Looking forward to more educational topics in Aviation Safety.

J.P. Soldo, ATP CFII

Via e-mail

Finding A CFI

I finally got around to completely reading the February 2012 issue and the article “Finding A CFI.” I was disappointed to see the author “bashing,” or at least misrepresenting, the military.

288

The type of experience he went through is not at all representative of our modern military aviators and I am offended he used a 50-year-old, outdated example. I was not a flyer while in the Air Force, but I worked directly with them and the type of behavior and the mindset stated in the article would not be tolerated today. One can find bad apples anywhere.

I was personally involved in several ground-training situations as well as being aware of scenarios in which individuals were given remedial training. The military is very selective today and generally takes pains to ensure success since there’s a big investment in the individual, not just “the system.” If you make the effort, unless you are medically disqualified, you are going to pass. The question then is, are you going to fly the aircraft you want? Not everyone is fighter-qualified. I have never had any training given “quite roughly.” Even so, why would that necessarily be wrong? Flying is demanding and always coddling students does them no favors.

I am now a student pilot and can say with some authority the discipline and experience my military training gives me is of great value. I think there is a great deal to be learned from the way the military does certain things.

John Wolf, MSgt., USAF (Ret.)

Bethel, Penn.