Because the final alphanumeric symbol in my aircraft’s registration is the number “zero,” (such as N67890), there is the occasional mixup by ATC, with a readback of “Sierra,” for the letter “S” instead of the number zero. This happens at times even though I am always careful to enunciate “zero” as clearly as I can (Zee-Row). Part of the occasional confusion is probably the fact that the zero comes at the end, where more often than not there is the expectation of a letter. I would venture a guess that there are more zero/sierra mixups than anything to do with the numbers three (which we are supposed to say as “tree”) or five (which we are supposed to say as “fife”). Although I suspect the chances of the FAA or ICAO (or whoever is in charge) changing the letter “S” designator to something other than “Sierra” is near zero. Any thoughts? Thanks.

William Cole – Petaluma, Calif.

As one who flies an airplane with registration ending in “S,” I feel your pain. My only suggestion is to clearly pronounce both of zero’s syllables distinctly, especially the last one, to distinguish it from the three syllables in sierra. That said, I’ve had controllers transpose my N-number more often than they’ve confused zero for sierra. There’s also the men and women (it’s usually men) who mistake the “S” as a five. So, you got that going for you.

I don’t have a fix for any of this.

AS THE PRO FLIES

Thanks for throwing all of us general aviation personnel under the bus with the second sentence in Mike Berry’s January 2022 article, “As The Pro Flies”: General aviation, however, is not as safe.”

Ronnie S. – Via web site

AS THE PRO FLIES II

There has been a grand total of one person dead in the last 14 years for air carriers in the U.S. For GA, one person is killed approximately every single day. It seems fair to point out this large gap and propose some effective means to narrow it.

Carl R. – Via web site

It’s obvious that commercial aviation’s safety has grown impressively since the days of Boeing 737 rollovers, TWA Flight 800 and even American Airlines Flight 587, on which the vertical stabilizer failed shortly after takeoff from John F. Kennedy International Airport. Many factors are responsible, among them better training and more widespread automation. If you always do things the same way every time, it’s easier to recognize abnormalities.

Porting that to general aviation is impossible, in large part because of its nature. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to duplicate the results, which often are less about professionalism than sticking to standard procedures.

IMAGE CONFUSION?

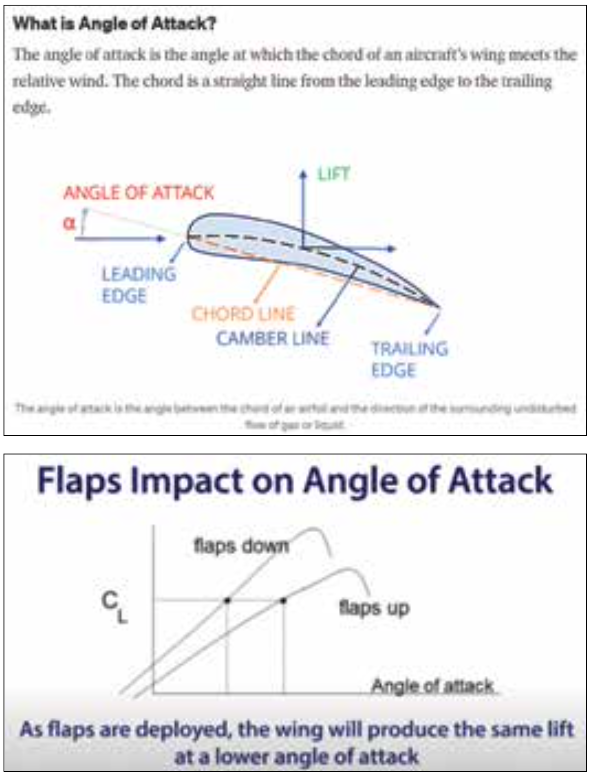

I think the FAA is right and your diagram in the April 2022 issue, accompanying your article, “AOA: Benefits, Choices,” is wrong. The extended flaps are changing the chord line and the pitch, not the AOA. Extended flaps are producing more lift and more resistance at the same AOA. Or am I totally off?

Richard Bieber – Via email

Welp. We’ve reproduced both images below. The top one comes from an April 9, 2021, post by the FAA FAASTeam’s blog on Medium.com. The bottom one is what we ran.

The thing is, the bottom one is from the FAA, also. It was captured from a YouTube video produced by the FAA’s Pegasus initiative (Partnership to Enhance General Aviation Safety, Accessibility and Sustainability), as discussed by the sidebar in which it appeared.

At the end of the day, though, the two images depict different things. The top one graphically describes angle of attack while the bottom one serves the purpose of reminding pilots that extending flaps alters that angle of attack.