These pages regularly urge new private pilots to go on to earn their instrument rating. Especially if you ever want to use a personal airplane for regular, reliable transportation, the rating is pretty much mandatory. If you’re content to only fly on good-weather days in search of expensive hamburgers and to abandon the peace-of-mind the rating confers, you also have to accept that not having it leaves you with fewer options, even when it’s clear and a million.

One of general aviation’s many attractions is the flexibility it affords even the VFR-only pilot who, on a whim, can turn off the radio and still cruise around most of the U.S. without talking to anyone. That same flexibility allows us to go “take a look” at weather conditions and decide whether to continue or return. But stuff happens.

Schedules and expectations must be met, while the weather-guessers miss a few along the way, maybe leaving you with the choice of risking a VFR-into-IMC mishap to get home or missing an important event. One of the problems is discipline: Even if you have hard-and-fast personal minimums, do you also have the self-discipline to just say no and turn around?

Taking a look is a time-honored practice and it shouldn’t surprise us when someone pushes a little too far. Hopefully, they come away with a newfound respect for what it’s like to be in marginal-or-worse conditions without good options. But it goes the other way, too. A lack of discipline can convince us that it won’t be so bad, or that the flyable weather between the departure and destination airports means what’s in the middle can’t be that hazardous.

The time-honored practice of “taking a look” at weather allows Part 91 pilots flexibility Part 135 and 121 pilots don’t have. There are two basic types.

Approaches

When a pilot decides to “take a look” at destination weather, he or she usually is opting to shoot an IFR approach, descend to the published minimums and determine if the runway environment can be seen well enough to land. If it’s not, you have the usual choices.

Departing/En Route

“Taking a look” also can describe departing into poor weather with the idea of determining if the flight can continue. It’s also used when it’s known that better conditions exist at the destination and the question is whether they can be reached by finding a way through, over or under the worse conditions.

BACKGROUND

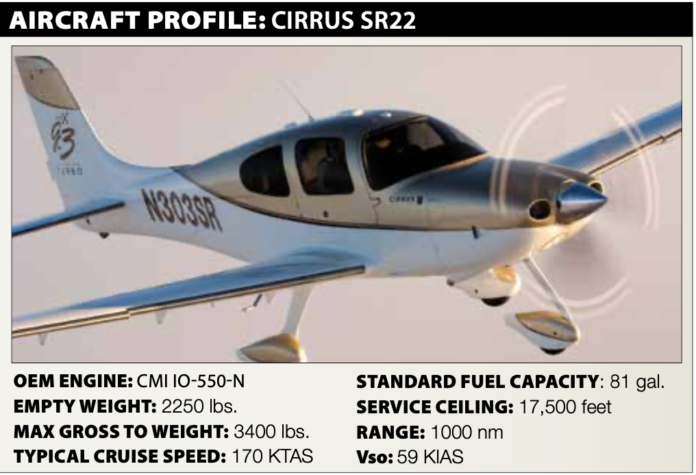

On October 1, 2017, at about 1043 Pacific time, a Cirrus Design Corp SR22 was destroyed when it impacted terrain while maneuvering in a remote mountainous area near Klamath Falls, Oregon. The non-instrument-rated private pilot and his passenger were fatally injured. Instrument conditions were reported in the area at the time of the accident.

Before departing at 1330, the accident pilot told an acquaintance he was on his way back to Medford, Oregon, a 52 nm hop. When the accident pilot spoke to the acquaintance, weather at the destination included a scattered-to-broken layer at 4000 feet agl with light winds. The pilot planned to depart VFR, climb above a cloud layer and find a “hole” near his destination for a VFR descent. If he couldn’t find a hole, he said he would return to Klamath Falls.

A few minutes later, an Oregon state trooper heard a low-flying aircraft headed generally from the southeast to the northwest. At the time, the trooper could not see the aircraft because the cloud cover was at treetop level. He heard the aircraft turn sharply to the left and stated that the engine was “screaming” like it was operating at full power. The engine noise returned to normal as the aircraft headed in a southerly direction and away from him, then he heard it started to “rev up and scream again,” as if it was in a hard turn. Shortly, he heard a loud pop and then complete silence.

INVESTIGATION

The accident airplane’s radar data show it leveled off at 6300 feet msl about five nm west of the 4095-foot-elevation departure airport at 1033:07. At 1041:52, after reaching 8700 feet, the airplane turned left and began descending, to 8100 feet, at 1500 fpm. Then it climbed to 9000 feet at an average rate of 4500 fpm, slowing to 125 knots groundspeed. From 1042:28 to 1042:40, the airplane descended from 9000 to 7100 feet msl at an average rate of descent of 9500 fpm and an average ground speed of 40 knots. The last radar return was about 638 feet west of the accident site, which was almost exactly at the planned flight’s midpoint.

The pilot had accumulated 170 total hours of flight experience, of which 52 hours were as pilot-in-command. Sixteen hours were in the accident airplane make and model, of which 10 hours were logged as pilot-in-command. The pilot had accumulated a total of three hours of simulated instrument time.

Observed weather at the departure airport about 40 minutes before takeoff included light winds, 10 miles of visibility and scattered clouds at 4800 feet agl (about 8900 feet msl). Ten minutes after the accident, the airport had an overcast at 4500 feet (about 8600 feet msl) and winds were from 310 degrees at nine knots with gusts to 16. At the same time, the destination airport reported calm wind, 10 miles of visibility, scattered clouds at 3400 feet and a broken ceiling at 6000 feet, or about 7300 feet msl.

Cloud-top data for the area was estimated at about 9000 feet msl. An Airmet had been issued for mountain obscuration at the accident location and time, while a second Airmet called for IFR conditions nearby. The NTSB report is silent on whether or how the accident pilot obtained weather information before the flight.

Much of the airplane was destroyed on impact, and all major components were present in the wreckage path, which was about 160 feet long and about 45 feet wide. Investigators found no anomalies that would have precluded normal operation.

PROBABLE CAUSE

The NTSB determined the accident’s probable cause(s) to include: “The noninstrument rated pilot’s decision to depart on a cross-country flight with en route weather conditions forecasted to be less than visual meteorological conditions and then to continue flight into instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in controlled flight into terrain.” Other than the minor quibble that it appears the airplane’s final minutes of flight were anything but under control, this finding places the initial link in the accident chain squarely on the pilot’s decision to take off.

In many ways, this accident is unremarkable; VFR-only pilots have been flying into instrument conditions since before Lindbergh. They’ve taken off in good weather and, expecting it to persist all along the route, failed to get or update their briefing. They’ve told themselves it can’t happen to them, or that their equipment will keep them safe and out of the weeds.

It’s pretty clear the airplane took off right before the bad stuff arrived. Waiting two or three hours for it to blow through, eliminating the need to take a look, might have forced the pilot to reschedule plans. Getting an instrument rating and learning how to use it would have been the better choice.