I have dealt with paper chart updates both as a student pilot and a professional pilot, and I can safely say I prefer EFBs. The worst luck I ever had with paper charts occurred before my private pilot checkride. I ended up weathered out on my first attempt, and the charts expired a few days before my rescheduled ride. The local flight schools near me were sold out, and I ended up driving an hour or so to the closest place I could find.

Looking back, I am 99-percent sure the DPE never even checked to make sure my charts were current. Either way, it was not worth the risk. After I finished instrument training the old-school way, I decided to buy my first iPad and a ForeFlight subscription. It was well worth the investment.

TRANSITIONING

Fast forward a few years, and I am flying for a charter operation. For 135 and 121 operations, EFB operations require a lot more effort than just hopping over to Best Buy and signing up for ForeFlight or Garmin Pilot. When first introduced, everyone worked diligently to obtain FAA approval for EFBs. Meanwhile and before FAA approval was given, operations types and pilots at my employer worked together to provide paper charts for basically the entire U.S. east coast and parts of Canada. Part of our preflight was making sure we had TERPs, en route charts and A/FDs (remember when the Chart Supplement was called that?) for all phases of flight. It really was not all that bad, but once the company got EFB approval, things did get significantly simpler. The huge amount of paper saved was just one benefit.

Something that jumped out at me during EFB training was the amount of new considerations these tools presented. Many tools designed to enhance safety are effective in doing so, but present new risks that did not exist in the previous infrastructure. I am not discouraging EFB usage in any shape or form. I think the positives vastly outweigh the negatives. That being said, there are some new threats that EFBs create that we will all do well to mitigate.

A few years back, I related the tale of encountering an overheated and useless iPad on the ground at Class B International. Without it, I had to “fall back” to using the data in my panel-mounted avionics. Which was fine, in part because I didn’t have far to go and in part because the data in the big box was current. At the time, I vowed to not let that happen again and started carrying paper charts for my local area.

But that was the worst of both solutions, since I still had to remember to update the paper aboard the airplane as well as the bytes in the tablet. Fortunately, there’s an even better solution for backing up your EFB: Get a second one. I now carry two iPad minis running ForeFlight and update them both at the same time. Both go into the airplane fully charged, one in a sturdy yoke mount and the other in an easily accessed seat-back pocket. I use a cigarette lighter adapter and a USB cable to keep the one in use fully charged. I also carry a battery pack, just in case.

When it comes to choosing the hardware for an EFB app, this is not an area in which you want to cheap out. Get a top-of-the-line device, with built-in GPS. Many Android tablets, for instance, come with GPS aboard, but you have to get the cellular version of an iPad to have an internal receiver (at least at this writing). That’s okay, because you want cellular data for those times when the FBO WiFi is down, you’re at your hangar or holding in the run-up area. These days, getting a sim card offering unlimited cell data is both easy and relatively inexpensive. And get a device with as much memory as you can—these apps can be resource-intensive. The only real decision you need to make is whether to go with a full-size tablet, a “mini” or depend on your phone. For me, a compact tablet is the sweet spot. — J.B.

BATTERY

Arguably the most important EFB actions occur prior to even getting into the aircraft. The first concern I have with any EFB is battery life. In a perfect world, our EFBs would be fully charged before any flight. As we have all experienced, life can throw curveballs and present challenges. For consideration, in the EFB programs I have used, the estimated battery depletion is about 10 percent per flight hour. Now this is far from ubiquitous, but the companies I worked for used iPads and replaced them every time the battery life percentage fell below 80 percent. You can check average depletion on your own flights to get a more accurate idea. A general rule of thumb is considering double the hourly battery depletion for any flight. For example, if your EFB depletes 10 percent per hour and you are planning on a two-hour flight, departing with at least 40-percent battery isn’t a good idea.

There are a few good ways to mitigate this issue entirely. Recently, I have seen panel-mounted clocks that have a USB charger installed, which is a great way to keep an EFB nice and charged. For something that doesn’t require installing equipment into the aircraft, portable battery chargers are cheaper and more powerful than ever. I was able to pick one up that would fully charge my EFB twice over. And, of course, there’s always the cigarette lighter adapter option.

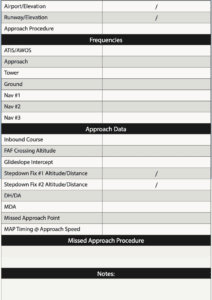

If I have instilled in you a fear of EFB failure, I apologize. But I do have a relatively simple solution. The table at right lists items you may need in a situation where your sole EFB has failed but you still need the information on it. You can keep it handy in the cockpit to use as a checklist of things you need to know when working with ATC to get down after an EFB failure or fill it out on the ground before takeoff. If you can find some decent weather and maintain VMC, that is definitely the best course of action.

On the other hand, if you end up at your destination, you can use this checklist to get the appropriate information from ATC to conduct an arrival and approach. The checklist is essentially a deconstructed approach plate, so most likely not every blank on it will need to be completed. Feel free to tailor it to your needs in any way that makes sense; the important thing is there is some organization for all the information you need and have no other way to access.

UPDATES AND DOWNLOADS

I like to ensure the EFB has the latest app and data updates the night before I head to the airport, so I am not stuck in the FBO waiting for downloads to complete. Chart requirements obviously vary depending on mission. Doing local pattern work on a VFR day and a 500-mile IFR cross-country can be the difference in about an hour’s worth of downloads, depending on how fast your internet is. Some EFB programs, like ForeFlight, make this process pretty simple through a pack function, which will download all applicable charts and plates for your route of flight, including flyover states. Others, such as FltPln, require selecting each state. The reason I mention this is because I worked with a flight crew that only downloaded the departure and destination airport information and experienced quite a shock when they required a diversion and both their EFBs had zero useful information displayed for the airport they chose. This is a classic example of life throwing those curveballs we spoke of earlier, and it is best to be prepared.

COCKPIT PLACEMENT

Something that still makes me chuckle about my first company’s transition to EFBs was the FAA’s requirement that the EFB be totally secure in the flight deck. It makes obvious sense, but so many pilots were unhappy about this. “I never had to secure the paper charts!” Well, yes, but how often were they dropped or shifted around unnecessarily in turbulence? An EFB also tends to hurt a little more if they bounce off your head (not that I have ever experienced this).

While this same legal requirement does not exist in basic Part 91 operations, it is not a bad idea to make sure your EFB is secured. The most common options I have seen are mounts, usually either a yoke mount or a suction cup on the windscreen, or a kneeboard. Both options work great, so it depends on preference and cockpit layout. Just out of curiosity, I did some digging to find any recommendations from the FAA about this. The only reference I could find that did not pertain to operators seeking approval for EFB operations was AC 91-78. This outlines the specific approval for pilots to replace paper charts and checklist with an EFB provided:

“(1) The components or systems onboard the aircraft which display precomposed or interactive information are the functional equivalent of the paper reference material.

“(2) The interactive or precomposed information being used for navigation or performance planning is current, up-to-date, and valid.”

Like the discussion earlier on battery life, there is no specific legal requirement for cockpit placement or securing the EFB. If you are anything like me, the first time it slides off your leg or gets lost in between the seats during rough air, it might a good idea to consider securing it.

If you haven’t done it before, it’s worth typing “FAA lithium-ion battery fires” into your favorite search engine. It is amazing how resilient the fires are. Flame retardant can slow the fire down, but it burns so persistently that the flames will reignite. Many pilot shops offer laptop and tablet fire containment bags, an example of which is pictured. This may be over the top, depending on your mission type, but consider how you might fight a fire like this if one occurred. When I fly, I have my EFB, my smart phone, and a backup battery at a minimum. Longer trips might have more, especially with additional passengers.

Just like airlines beg passengers not to check bags with lithium-ion batteries, it is a good practice to make sure they are semi-accessible. If I am alone in a Skyhawk and I start to smell smoke coming from the baggage, there is nothing to be done other than land ASAP. That is a phenomenal plan anyway, but being able to identify the fire gives the best situational awareness and the best chance to fight the fire.

FLIGHT OPERATIONS

This is truly where EFB operations shine. I remember the first time I used ForeFlight for a cross-country, rather than paper charts, a paper nav log and all the associated work. At any time, I could look up information for adjacent airports in case I needed to divert. I did not have to hunt for approach plates, getting so confused because the TERPs had the Martha’s Vineyard Airport listed under Vineyard Haven, Mass.

If I did need to scope out some options, gone were the frantic whiz-wheel calculations of fuel required and time en route. It felt similar to the first time I was allowed to use the computer at the school library instead of searching for everything in the card catalog and hunting for books, hoping they were not checked out already. I want to make this point because I think it dovetails nicely into our first threat for flight operations with EFBs.

DISTRACTION

Distractions are a constant threat in the cockpit. It could be a busy ATC frequency or a sick passenger. Anything diverting the pilot’s attention away from managing the flight path needs to be addressed and prioritized. I have even said the words “aviate, navigate, communicate” to myself in high-workload environments. With proper use, EFBs can help enhance situational awareness and help keep the pilot ahead of the airplane. Occasionally, the opposite occurs.

I was flying with a student into a busy, unfamiliar airport. Somewhere on base-to-final, the student realized they were not sure about the taxi route and attempted to pull up the airport diagram on their EFB. Nothing disastrous occurred, but they did get a little slow and diverted from the flight path. In this instance, the student caught their mistake and corrected. After we landed, the tower said, “Left on Bravo, ground on point nine.” The student read back the clearance and we came to a stop clear of the runway.

At this point, I wanted to emphasize a point, so I told them to close the EFB app, open it up and pull up the taxi diagram again. It took about 15 seconds, maybe 20. Once they were ready, situational awareness intact, they contacted ground and had an uneventful taxi to the ramp. The point of this story is that improper use of the EFB can create unnecessary distraction. It is a great idea to look over and brief the taxi before landing, but it must be done during a non-critical phase of flight, not when turning final. If it is missed, then worry about it on the ground.

FAILURE

Just like any technology, EFBs can fail. Some can be benign, like the device shuts off and does not restart. Others can catch your attention, such as an EFB overheat leading to a lithium-ion battery fire. The accompanying sidebars discuss options for both these scenarios, but the most important strategy is to have a plan.

For many pilots, it is using their smart phone or panel-mounted GPS as a backup source for the most vital information. Others keep minimal paper charts for local airports in the plane, just in case. In the end, this is largely a thought exercise because, on the whole, EFBs rarely fail and the footprint for handing it can be vastly different depending on the failure.

A PILOT’S BEST FRIEND

As much as I love my local pilot shop, I am very happy I no longer have to purchase VFR sectionals, IFR en route charts, TERPS and chart supplements every 28 to 56 days. The EFB has come so far in such a short amount of time, with so many additional capabilities beyond charting, like weather and traffic, developed in the last few years. With some planning and consideration, these tools can help keep the pilot in front of the aircraft with minimal risk.

After a career as a Part 135 pilot, flight instructor and check airman, Ryan Motte recently got hired by a major airline and is now flying as a Part 121 first officer.