As long as we fly aircraft with retractable landing gear, there will be gear-up landings, a phenomenon not unique to any one make or model of airplane. Read the daily FAA aircraft incident reports—the vast majority of which do not meet NTSB reporting criteria and so will not be investigated further or included in official accident statistics—and you’ll find several gear-ups each week. Talk to aircraft parts suppliers and salvage yards, and you’ll find there are even more than appear on the FAA website. Although there are effective techniques and mitigations for avoiding gear-ups, it’s no wonder the fatalistic phrase “there are those who have, and those who will” have a gear-up landing is so well-known.

The gear-ups we know most about are those that are recorded live and broadcast on the internet or local television news, with predictable commentary. If the local TV news team was in place to witness an airplane landing with its gear partly or fully up, it’s because they knew it was going to happen. Which means the pilot also knew, and told others. Those episodes are not the typical “oops, I forgot” distraction event. It was the result of a mechanical failure the pilot could not correct in-flight (or may not have known how to correct). The time between detecting failure and turning final was great enough that the pilot had time to prepare him/herself and first responders.

How might we prepare for such a landing? What options do we have, and how might we choose from among them? What can we learn from this about preparing for other abnormal and emergency scenarios?

SCENARIOS (DON’T) UNFOLD

Most of us extend the gear when we begin our descent from traffic pattern altitude in a visual landing, and at the final approach fix inbound on an instrument approach. The technique “gear down to go down” is common to many training providers and type club teachings. Some pilots like to extend the landing gear farther out so they can detect a gear failure sooner. That’s a valid technique, too.

In some airplanes (e.g., Bellanca Super Viking and Cessna Cardinal RG), there are big pitch excursions and lateral movements while the gear is in transit, and you might want to get those out of the way before starting down a glideslope. Regardless of your gear extension SOP, if you start the landing gear down and the gear stops unfolding, that’s where the intentional gear-up landing scenario begins.

First, you must detect when a problem occurs. When you extend the landing gear you should confirm gear operation in three ways:

The gear sounds right. The motor and/or pump sounds like it always does and runs for about the same amount of time as usual. The change in wind noise sounds normal as well.

The gear feels right. The airplane’s attitude changes as expected, and it settles into the descent angle and rate it routinely does.

The gear looks right. The gear position indicators indicate correctly: three green lights, a gear pointer, no in-transit light—whatever is correct for the airplane you’re flying. If you have exterior gear mirrors, or one or more tire is visible to you (and passengers if you have them), the landing gear legs you can see should look normal.

Only after you confirm the gear sounds right, feels right and looks right, can you be assured it has extended properly. Let’s say it hasn’t. What’s next?

If the gear did not start down at all, if it looks down but the indications don’t confirm it, or if the gear legs are uniformly down but the system stopped in transit (which usually pops the circuit breaker), you may be able to solve the problem by manually extending the landing gear. Find some open airspace well away from traffic and the airport, pull out the checklist and complete the emergency gear extension procedure applying to your airplane. If all goes well and indications now confirm the gear is down, come back and land—smoothly and carefully, and then have the system checked by a mechanic.

It might not be a good idea to “cycle” the gear by retracting it and trying again to extend it. It’s common practice and human nature to “give it another chance.” But history shows that if a gear pushrod or rod end bends (a common reason for incomplete extension that pops the breaker) that running the gear the other direction can break it completely and leave you stuck with gear legs partway out. Manually extending the gear may put less force on the system and may permit this one last down-and-locked result. If full extension is still possible, the manual procedure will probably work.

Three times I’ve picked up the phone while working at the American Bonanza Society office to find the caller is on his cell phone in an airplane trying to get the landing gear down. Two of those times I’ve been able to help the pilot complete the manual extension procedure successfully. The point is, if you’ve exhausted your efforts to troubleshoot the gear to a successful outcome, your attempt didn’t work and you’ve run out of ideas, think outside the box. You may be able to phone an expert for help.

BUFFERING

“Buffering” is a computer term that describes a period when a program is loading. That’s when you see the little hourglass or the “spinning wheel of death” on a computer screen. A buffer is also a space or a barrier between two things that provides protection. In the context of our gear malfunction, the first step is to create a buffer: a time between now and your eventual landing to address the problem, a space between you and the ground to address it safely. Climb to a safe altitude away from the airport. Tell controllers you need an altitude and a heading, if necessary, and ask them to keep an eye on your altitude and location while you investigate the landing gear system.

YOU’RE STUCK WITH IT

If one or more gear legs won’t extend, you now may have a choice: land with the gear where it is, or see if you can retract the gear and land gear-up. Pilots argue both ways: If the nose is only partway down but the mains are locked, land smoothly and let the nose down gently as you land. Alternately, reset the breaker if it’s popped and retract the gear if possible, and then make a smooth belly landing. If the mains are down and the nose gear is not, I’d probably try the first way. If one of the mains wasn’t locked down, I think I’d aim for the gear-up landing if I can retract the gear. But the choice is yours, and now’s the time for you to think about it—before you’re flying around in a broken airplane and only then consider your options.

PAVEMENT OR GRASS

The POH/AFM often advises to choose a firm sod or foamed runway. This is not to minimize airplane damage; unpaved surfaces generally cause much more airplane damage than pavement in a gear-up landing. The fact that the recommendation often includes “foamed” is a clue: the foam is a fire retardant, not a cushion. The correct technique for landing on a foamed runway is to touch down before the area that is foamed so the airplane comes to a stop in and is covered by the foam. Similarly, the suggestion to use a firm sod runway is more about minimizing the chances of a fire. Search YouTube for video of gear-up landings and you’ll see they tend to create quite a bit of sparking from friction—this is very obvious if it happens on a cloudy day or at twilight.

Gear-up landings almost never result in an aircraft fire, however, so you may choose to do a smoother touchdown on pavement. The airplane will slide farther on pavement then it would on grass too, and this reduces the deceleration forces you and your passengers will experience. Most pilots, including the test pilots I’ve talked to about this, would land on a paved runway. I’ve thought about it a lot and my personal preference is a wide, paved runway at a tower-controlled airport with fire trucks and ambulances (and a bartender—ed.) standing by alongside the runway. I’d fly quite some distance before an intentional gear-up landing to meet those criteria. Now’s the time for you to think about what you’d do in similar circumstances.

There are other abnormal and emergency scenarios that put you in a position to plan your response. Examples include a partial-panel approach, the aftermath of an electrical fire that you were able to extinguish and a single-engine approach and landing in a twin—can you think of more? For these and other planned emergencies:

• Think about them beforehand.

• Create a time and distance buffer to respond safely and deliberately.

• Declare an emergency—there’s no downside.

• Use the checklists.

• Troubleshoot to try to reach the best possible condition, using checklists and your systems knowledge.

• Get the help you need, whether it be technical experts by phone or radio to help with your response, or first responders to stand by in case you need them.

• Brief yourself and passengers.

• Make a final checklist review before setting up for landing.

• Fly precisely for as long as you can control the airplane.

• Assertively direct the evacuation once the airplane comes to a stop.

FLAPS OR NO?

Most POHs/AFMs also suggest using flaps “as necessary.” One goal is to land at the slowest safe speed, and flaps can decrease touchdown speed quite a bit. Pavement or grass, this reduces impact inertia to get the airplane stopped sooner. The airplane will float a lot more in the flare with the gear retracted, and using flaps helps you touch down at your intended spot.

Some pilots would land with flaps up to protect them from damage. The sad truth is that the biggest part of the repair bill will be propeller replacement and engine tear down, inspection and reassembly, and with current repair prices and airplane values, a gear-up landing very frequently “totals” the airplane anyway. Consideration for protecting the airplane should focus primarily on what will assure the best outcome for the airplane’s occupants, not the airplane itself.

BRIEFING

After trying to fix the problem, setting the gear in whatever position you feel is optimal under the circumstances, aiming toward the best landing option and arranging to have help available if you need it after landing, read through the checklist a couple of times so you know what you’ll have to do on short final. Then, brief any passengers. They should already know how to use normal and emergency exits from your (required) preflight passenger safety briefing. Remind them now.

Have passengers secure loose objects in the cabin, and then tighten seat belts and shoulder harnesses to the point they are uncomfortably snug. No shoulder harnesses? Use a coat or a pillow or anything else soft to cushion their faces when the airplane decelerates. Unless the POH/AFM suggests otherwise, as you get near the ground you should unlatch the doors and/or windows for ease of evacuation.

So tell your passengers what you’re going to do so and why, and what it’s going to sound like when you do. Remind them that after the airplane comes to a stop, you will all exit the airplane immediately, removing headsets and leaving all baggage behind. Depending on the airplane seating and available exits, you may have to designate the order passengers will leave the airplane. Tell them before takeoff and remind them now. Advise you’ll all move away from the airplane past the tail to several airplane lengths away where you will gather and assure everyone is safe.

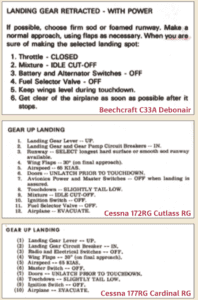

We looked at the POH/AFM guidance offered for three retractable piston singles: a Cessna 172RG Cutlass RG, a Cessna 177RG Cardinal RG and a Beech C33A Debonair. They all say pretty much the same thing, but do it differently, emphasizing some things (e.g., open the doors) and forgetting other items: What to do with the fuel selector and/or mixture control when intentionally landing a Cardinal RG without its gear extended?

For example, all include turning off the master switch/battery, about halfway through the checklists (when the 172RG’s landing is assured ), killing electrical power. But one adds the avionics master switch. Both Cessna checklists advise opening the doors before touchdown, but the Beech version is silent. All three are relatively consistent, though, when the airplane comes to a stop: Get out.

The three examples also offer advice on technique, which is consistent for both Cessna products: touch down slightly tail low. The Beech checklist, instead, simply advises to keep the wings level during touchdown.

DOING IT

Coming down final approach, if you’re not going to touch down where you expect, go around and try again. You’re not committed just because the gear is partly or fully up. When you’re sure of making the selected landing spot and after extending flaps if that’s your choice, follow the checklist.

As noted in the sidebar above, not all gear-up landing checklists are alike, even from the same manufacturer. Your objective here is to land wings level, under control and at the slowest safe speed. Keep the wings level during touchdown and use whatever directional control (rudder) you have remaining as the airplane slows.

Get clear of the airplane as soon as possible after it stops. Airplanes land gear-up by accident all of the time (unfortunately) and there’s almost never an injury or a fire. But there is always a chance: When the airplane stops, use your command voice to direct passengers to get out, fast, in the order they were briefed, and to get well away from the airplane.

I can only imagine how busy and distracting it would be when your gear won’t extend and you tell your passengers you need to try to fix it and, if that doesn’t work, land gear-up. It may be difficult to consider everything for the first time in such a situation, and know the extra things you need to do—briefing and calming passengers, preparing the cabin, popping open the doors or windows, planning the evacuation, etc.—that are not in the POH/AFM gear-up landing checklist.

Your success depends on thinking about and planning for this beforehand. Your actions, and your options, are only partly described in your airplane’s emergency procedures checklist.

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.