Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an even greater degree than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity or neglect.” You probably have seen this quote in a pilot’s lounge somewhere, perhaps along with a photo of an early biplane stuck in the only tree for miles around. The quote is real, attributed to Captain A.G. Lamplugh, who at the time (1931) was chief underwriter and principal surveyor of British Aviation Insurance Company. We’re not sure about the biplane and the tree.

Of course, we pilots know flying is totally inherently dangerous, on account of laws, like the law of gravity. And other stuff—like weather, other aircraft, balloons—which we know aren’t really “aircraft”—running out of fuel, structural failure and spatial disorientation, to name just a few dangers. And oh—radio miscommunication.

Why are some radio miscommunications dangerous? Well, a pilot can dork up a radio call—or two—and taxi right onto an active runway and get speared by another aircraft, for one reason.

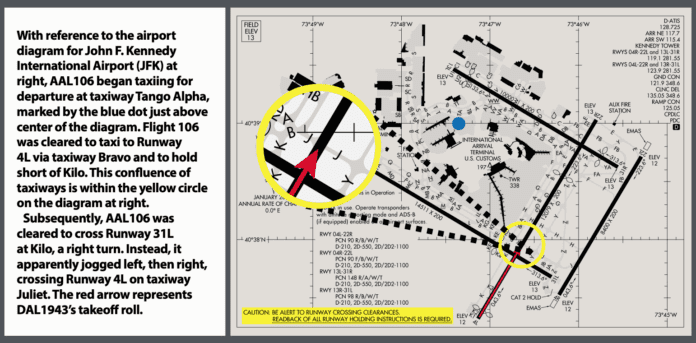

A BAD DAY AT JFK

Like American Airlines Flight 106, a Boeing 777 heading for London Heathrow, almost did on Friday, January 13, at JFK. You probably heard about this event, which was narrowly avoided when, among other actions, a tower controller noticed the AAL flight taxiing across Runway 4L in front of a departing Delta Air Lines Boeing 737, Flight 1943, and urgently transmitted, “Delta 1943, cancel takeoff clearance! Delta 1943, cancel takeoff clearance!” (With coolness factor jacked up to 11, a voice from the Delta 737 merely responded, “Rejecting.”)

At roughly the same time, on the ground control frequency, another controller transmitted, “American 106 heavy—American 106 heavy, hold position! American 106 heavy, hold position!” Thankfully and according to reports, the two airplanes never got closer than about 1000 feet as the Delta 737 stopped on the runway before taxiing clear, and the American 777 cleared the runway then stopped on a taxiway. When the smoke cleared, the Delta flight returned to the gate while the American trip-seven’s crew wrote down an ATC telephone number to call about a “possible pilot deviation” and then launched for Heathrow.

How does this kind of thing happen? Aren’t there rules for making radio calls? Isn’t there a standard lexicon of words pilots and controllers use so both parties understand each other? The answers to those questions are: Humans are involved. Yes. Yes. The only people who came out of this goatrope smelling like roses are the Delta crew.

CUTTING CORNERS

Available ATC audio for this incident reveals what appeared to be a typical day at JFK. Controllers and pilots alike were tossing out and fielding runways, taxiways and hold-short instructions as they normally do, perhaps omitting a few syllables from the FAA-recommended phraseology but communicating enough information to make logical sense.

In turn, it’s the crew’s responsibility to read back the salient data, preferably in the same order it was delivered. Based on publicly available audio, it’s not clear everyone was doing that. There’s also the complacency that comes from obtaining and processing information like taxi clearances day in and day out, while running checklists and monitoring the other pilot. We come to expect one thing but forget we can receive something else.

The American crew may have written down Runway 4L, but at some point their expectations seemed to change to Runway 31L. Again, based on what’s publicly available, ATC only said the runway number once, and American 106 never seemed to read it back. So that got lost in the fog of war. Pretty much the most important part of the radio calls was the “taxi to Runway 4L” part. Seems like sometimes an error is so big, no one expected it to happen. Both parties expected something else.

So if a major airliner at a towered airport with two—no, three—pilots on board can screw up and almost cause a huge Tenerife-like fireball, just think what a mere GA pilot—me, for example—can do by miscommunicating with ATC.

At the “out base” where we landed and refueled our USAF T-38s after a cross-country and before the flight home, I was cleared to taxi to “intersection echo” on the active runway, and I dutifully read that clearance back without thinking. (The “without thinking” part is key here.) Immediately one of our instructor pilots (IPs) from Vance AFB came on the radio and said, “Disregard that clearance, request full runway for Pokey 25.”

The ground controller told me where to taxi, and I did. Later, back on the ground at Vance AFB, one of the IPs came up to me and said, “Lieutenant Johnson, what were you thinking, accepting that intersection takeoff clearance? This T-38 needs 8000 feet of runway, and that would have only been 5000 feet!” The IP had a smile on his face—I had screwed up, like students do—that’s why he came along in the mother ship to watch over us. I had never been told to takeoff from an intersection before, and was expecting a full-length runway taxi instruction, like I always had a my home base. It was a good lesson—ATC might tell me to do something that I wasn’t ready for.

BEEN THERE, DONE THAT

I was a student pilot in the U.S. Air Force at Vance Air Force Base, Oklahoma, on my first solo cross-country flight in a T-38. The Air Force sent about 10 of us solo students with one mother ship—two instructor pilots on board—to act as adult supervision.

So I blast off, switch over to departure, get cleared to 17,000 feet. I carefully level off at 17,000 feet, ever so careful to hold altitude exactly—no autopilot. Then ATC came over my earphones, “Pokey 25, say altitude.” I said, “Pokey 25, seventeen thousand feet.” And looked carefully at the altimeter, which read “16,000” right on the nose.

I said, “Pokey 25, climbing to 17,000 feet,” and that was the end of it, no “call this number,” etc., because the controllers knew, from our call signs, that we were all first-time T-38 solo cross-country students, and were ready for some errors. Whew!

Slang can get a pilot in trouble, too, along with shortened radio calls. The tower at Frederick, Maryland (KFDK)—home of AOPA—can get a little snippy. They’re tired of all the students making mistakes, maybe. One day, they called out traffic to me, and asked, “Skyhawk 12345, do you have that traffic on final in sight?”

I saw the traffic, keyed the mic and said, “Skyhawk 12345, tally.” There was some silence, and then the tower guy said, in an overly-clear, condescending tone, “Tally? Did you mean ‘traffic in sight?’” I suppose if I hadn’t seen the traffic, saying, “Skyhawk 234DJ, searching, no joy” instead of “negative contact” would have popped all their mental circuit breakers.

Another time, blasting along the Sacramento Valley in a T-38 at the usual 300 knots, Sacramento ATC gave me an instruction and I responded, “Roger that.” The controller came on the freq and said very calmly and slowly, “Roger that? Did you mean ‘affirmative?’” I said meekly, “Affirmative, Roper 25.”

We copilots had gotten into the habit of saying, “Roger that” to each other in conversation, and, oops, I made the mistake and said it on the air.

Other ways radio calls can be dangerous is if pilots step on each other’s calls in the pattern. At KJYO, the Leesburg (Va.) Executive Airport, my former home base, things often got quite busy, and the tower and ground controller were the same person. Many times pilots stepped on each other, with the annoying radio squeal.

I found that monitoring tower as I taxied out on ground freq kept me from stepping on the tower transmissions, and vice versa. When “ground” was reading a long clearance, and the pilot read it back, it paid off to be listening to the ground frequency while flying in the pattern, so as to not step on the call.

In the recent American 106 runway incursion, one news article said that American 106 was still on ground frequency, and therefore didn’t hear the tower clear Delta for takeoff on Runway 4L. Ahem. Airliners have a LOT of radios on board, and they weren’t monitoring tower freq as they crossed a runway at JFK?

The lesson for me is to use the two radios I have to monitor multiple frequencies, like tower, ground and guard (121.5). With a modern audio panel, it’s no more than a couple of button pushes to do this.

GOING CASUAL, HURRYING

When things are going well, pilots can get casual on the radio; we’ve all heard it, done it, maybe. I was flying around some horrendous thunderstorms near the east coast, using flight following on a VFR flight. I was staring at huge blue and white towering cumulus. Absolutely stunning. Occasional lighting. I felt like a weather nerd for gawking at the huge, weird-colored clouds—until I heard a Southwest Airlines flight deep in the towering cu canyons reply to an ATC Pirep request with: “Southwest 123—this looks like an alien landscape in here.”

A too-casual attitude has its downsides, of course. One time, I was at Falcon Field (KFFZ) in Arizona, wasn’t monitoring tower and taxied toward the active Runway, 22L. Well, the taxiway is skinny, and there’s no runup area at the end, so by the time I’m ready to go and switch to tower, there was an angry Cirrus driver behind me. So I hurried my pre-takeoff checks, took off in a hurry, embarrassed to have held up the guy behind me in the Cirrus.

Hurrying is not good, especially at KFFZ. A pilot has to stay out of the Phoenix Bravo airspace, Scottsdale’s Class D airspace, and whoa—watch the mountains!

My poor radio usage and hurried state caused me great stress for a minute or two on my little VFR flight. I had to take off from the 1400-foot msl airport, stay below the Bravo’s 2700-foot msl shelf, hang an immediate right (toward Las Vegas) get above 4000 msl to avoid Scottsdale Class D airspace but stay below the 4000-foot Bravo shelf, and avoid the 4067-foot peak right there in my face. Nice.

Listen

Part of communicating is listening. That’s especially true in the party-line atmosphere that is ATC. A center controller tells us, “Sometimes while you wait, you may even hear a relevant report given to another pilot along your route of flight, saving you a call.”

Readbacks

First and foremost, ATC uses readbacks to verify the clearance was received. Another reason is what we’ve called “double-secret verification”: By listening to the pilot’s readback, the controller can verify the correct information was transmitted.

Be Clear, Concise

“Thinking on frequency or sounding uncertain slows everyone down,” that center controller once told us. Wasting time or sounding unprofessional often also is guaranteed to put you at the end of the line when you have a request.

EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED

All my fault, this stress, because I had let the radio put me into rush mode, hurrying, even though there was no reason. Had I looked at the taxi diagram closer and been on tower frequency earlier, I would have seen there is no runup area, and I would have heard the angry guy behind me before he got angry.

There are so many ways to screw up on the radio, and the screwups can cause a deadly chain reaction. Whether imprecise language—slang—creeps in to our badinage or we omit details when we think they’re obvious, screwing up our communications with ATC and other airplanes at non-towered airports can have consequences.

To help fight expectation bias in radio communications, it pays to slow down—just a bit—take notes if necessary, listen, read back everything and get that all-important ATC reply “read back is correct.” Oh, and think before I talk.

Of course, ATC makes mistakes, too. The other day in Fargo (KFAR), I asked for taxi clearance from the “north GA hangars to the south GA area” and ground control gave me some weird, impossible instruction to use taxiways that didn’t connect to where I was parked. So I queried.

The ground controller said, “Ohhh, I thought you said you were at the main ramp.” He had heard me clearly, but it didn’t register, and he gave me instructions to taxi from a place I wasn’t at. He “heard” what he thought he was going to hear.

More expectation bias: One sunny day with calm winds at Beale Air Force Base, I had a young T-38 IP scold me for my horrible radio call.

This was about one second after I was given instructions by tower, on a touch-and-go from Runway 15, to do a “right ninety, left two-seventy to Runway 33, cleared touch-and-go,” and proceeded to make a normal climbing left turn to the Runway 33 downwind.

Oops. Expectation bias again. I heard what the controller said, but it just didn’t register. I was so ready to do a normal climbing left turn to Runway 15 downwind, that I missed the tower’s transmission. I was going for the wrong runway.

The IP took control of the aircraft momentarily, scolding me: “You copilots and your radio calls! They’re gonna kill you someday!” Later, on the ground, he said I had “the copilot syndrome.” He said he noticed we copilots didn’t pay close attention to radio calls, because we weren’t flying. We heard the words, but they were often just fuzzy noises, and we got the calls wrong. Then the aircraft commander or instructor pilot would correct the call—and we got used to it, expected it—so we didn’t pay maximum attention to radio calls.

Matt Johnson is a former U.S. Air Force T-38 instructor pilot and KC-135Q copilot. He’s now a Minnesota-based flight instructor.