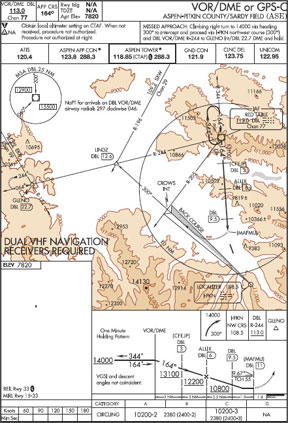

Most for-real instrument flights end with an approach. Once we leave the final approach fix (FAF) in IMC-or enter it beyond the FAF-its the real deal. Thankfully, the approaches most of us fly these days are pretty standardized, almost to the point of being boring. Almost. Theres a world of practical difference between a rural-airport ILS and an urban localizer back-course circle-to-land 288 procedure, to pick two. But-presuming both are published by the FAA-theyre all safe, right? Probably. The FAA has a cadre of engineers dedicated to developing instrument approach procedures, or IAPs, that comply with its standards. Once the procedure is developed and all its parameters decided, the agency sends out a flight check aircraft to fly the approach from all angles, including the published missed approach, and verifies it performs as its designers intended. But that doesnt make them all the same. Not created equal For one obvious example, flying a normally aspirated light single into Aspen, Colo., IFR isnt for the faint of heart. As the approach plate on the opposite page demonstrates, the circling minima can be higher than many of us are accustomed to flying; one of the areas minimum safe altitudes may be higher than your airplanes service ceiling. Even if it isnt, getting there may take too long and put you too close to a mountain. If flown correctly and as designed, yes, published approaches are “safe.” What makes an approach dangerous, or less safe, is when we dont fly them the way their designers intended. There can be a wide range of reasons an approach is “dangerous,” most of which involve the procedures complexity, but the bottom line is that, when flown correctly, each published procedure provides a defined course and altitude we can fly to put us in a position from which to land. How we get there is up to us. Referring back to Aspen, the facility can be such a handful the FAA requires airline crews to be specially trained and qualified before they fly it. (How many approaches do you know where they put a localizer on the side of a mountain solely to provide the level of precision guidance necessary to survive the missed approach?) Then there are some approaches I remember in Alaska where the missed approach climb gradient prompted some TERPSter with a wry sense of humor to add a note something like, “Caution. Successful missed approach unlikely.” Okay, Aspen is an exceptional example. What constitutes a dangerous approach, anyway? Well, there are certainly elements in some approaches that are more difficult to fly than others. Personally, I struggle with non-precision approaches with lots of stepdown fixes -I can never seem to get down to the MDA before I get to the VDP. But thats only really an issue when youre flying the approach at a high speed, say 150 knots. Things just seem to happen too fast at that speed. On the other hand, at typical GA approach speeds of, say, 90 to 120 knots, those stepdowns get a lot easier. In fact, everything about the approach gets easier when theres more time. Timing is everything So why does having more time make an approach easier? Well, with more time we can think things through more carefully, were not quite so task saturated and were not rushed, making more mistakes. Now, theres something to dig into! So then, well define any approach where you have to rush as a dangerous approach. Yeah, but we still havent really answered “Why?” and perhaps more important, “What can we do about it?” Time is a luxury thats sometimes just not available to us on a busy approach. Step downs, frequency changes, radio setup, timing requirements, heading changes and corrections all seem to happen at the same time. When things happen quickly or in bunches we tend to overlook some items. Not good. We sure dont want to overlook tuning in some critical frequency or noting passage of a stepdown fix. Okay, but how did we get so busy? Good question. We probably werent adequately prepared or adequately rehearsed. Theres the rub! I recently went through about three weeks of simulator training, five days a week for about four hours a day. Grueling. We did lots of stuff, handling enough abnormal conditions that it would take all the pilots flying that airplane most of their lives to experience even a small percentage of them in real life. We flew approaches, too. The same four or five approaches over and over and over again. The first week in the sim I was so far behind the airplane that I was even getting my tangue all tungled up. I knew what to do and I knew when to do it, but that knowledge was only recently learned and I had to think about it, think through each step carefully. The more I had to think about it, the more task saturated I became with the little stuff. Then, suddenly one day, everything went well. Never mind that the next few days were horrible again, I actually got through that one day feeling relaxed and prepared. I no longer had to think about what to do; I

Walk? Or Chew Gum?

OK, but how do you get to that point? You know the answer. Well, actually there are two pieces to the answer. First, Im sorry to have to say, is proficiency. I dont mean taking an IPC every six months. Im talking about the kind of proficiency that

288

allows you to drive your car on a winding mountain road and talk on the cell phone (hands-free, of course) while eating a cheeseburger. (Its an example, folks. No nastygrams, please.) Yeah, the kind of proficiency where you really dont have to think about driving because youre so very proficient that it all comes automatically. Im certainly not that good in the airplane but the best pros really are.

I remember once riding along with this fellow who had about a gazillion hours in the Guppy (B-737) he was flying. Amiable fellow, liked to talk. In fact, I was sitting in the jumpseat behind the two crew-we were talking almost constantly throughout the flight and he would frequently turn around to look at me. Oh, and he hand flew the entire flight.

Yes, in RVSM airspace where youre supposed to be on autopilot, he hand flew. At first, I was a bit nervous about this, but after a few minutes of watching his altitude and heading not vary by as much as 15 feet and a degree or so, I relaxed. Even on the approach he kept talking and turning around to look at me. I thought the HSI needles were broken because they never moved from the exact center. The landing? Well, I wasnt sure we had landed until he stowed the thrust reversers and the controller told us to contact ground. I want to be that good when I grow up. You should, too.

Now, realistically very few of us will ever get that good. Flying is a bit more challenging for the rest of us and does require some concentration on a complex approach, regardless of how proficient we might be.

No easy Answer

So, how do you get to an acceptable level of proficiency? The only way I know is to practice. Practice. Practice a lot. Ill assume that you can fly an approach with a certain degree of precision. Sure, youve got to practice from time to time to retain that level of precision. But, thats not what Im talking about when I say “proficiency.”

Instead, Im talking about being able to execute the procedures comfortably-taking those flying skills that you have and putting them to work on a practice approach over and over, until the other procedures are automatic. Use a desktop simulator on your PC and practice, fly with a buddy, anything. Build your toolbox of procedures for approaches (configuring from the en route structure to vectors and setting up the approach, stepdowns, heading changes, landing transitions, missed approach transitions, tuning, etc.) to the point where you could do them while carrying on a conversation and eating a cheeseburger. Figuratively speaking, of course.

Bell Ringers

Lets look at a couple of those tools, starting with setting up for the approach. Enter as much stuff into “the box” as you can as soon as you know what approach youll be flying. Before you even take off, you can make an educated guess of which approach by checking the surface wind forecast for your destination.

Your response to the first vector should be like Pavlovs dog: Read back the heading, then immediately do the rest of whats required, stuff like flipping over to the approach nav frequency, selecting the correct nav source and setting the course (OBS), configuring “the box” and the autopilot/flight director if youre using one, etc. Then just cruise around on vectors until you hear the magic words, “Cleared for approach.”

As I said, stepdowns are my nemesis. Theyre not difficult, as long as youre prepared. Once on final, be aggressive about watching that distance to the next fix and start the next descent a 10th or so of a nautical mile early. Be automatic when you begin to level off at the next altitude and bring in more power and check for the next stepdown. Like Pavlovs dog, remember?

Meanwhile, your flying skills need to be good enough to hold heading and altitude without worrying about it. If you have to concentrate on those basic tasks, youre likely missing the brain cycles needed for other tasks.

What Comes Next?

The next critical event is arriving at the minimums. Flying this is just another level-off at the end of a stepdown, but there are a few more tasks to do. First, obviously, start looking carefully out the window. If you see the runway (or environment) and are in a position from which to land, you may continue the descent-or initiate one-but have the discipline to do so at normal descent rates; overcome the newbies penchant for diving to the threshold.

Watch your progress to your VDP, beyond which youll miss anyway. Youve also got to be thinking about the missed approach. Got an autopilot where you can enter the missed approach altitude? What about if you see the approach lights, but not the runway? What will the altimeter say when youve reached the permitted 100 feet agl? What if the final isnt aligned with a runway, or even with the airport? Know where to look for the runway you need? Know which way to circle the shortest way around to the landing runway?

These all are things you have to do or think about automatically and you simply dont have the luxury to try to remember them all. Like Pavlovs dog, right?

When youre proficient-or conditioned-well enough these things all come automatically, then the approach is leisurely and youve got lots of time. Struggle with these things too much and, well, it might just be a dangerous approach.

One Last Item

A bunch of paragraphs ago I mentioned that there are two prerequisites before one can realize the benefits of all this approach proficiency. So far, we just talked about the proficiency or conditioning to know procedurally what to do, when to do it and, of course, how. The other element is the approach briefing.

Yeah, youve looked it over and you know the high points like frequency, course, MDA and such, but do you really

know the approach? Probably not. Short of memorizing it (which is a good idea if you can pull it off) the best briefing goes beyond the setup and is really a visualization of each step of that approach-armchair flying.Think through each stepdown fix. Realize what kind of a descent rate will allow you to reach the next step down at altitude. Remember where to look for the runway. Be prepared to descend to 100 feet agl. That kind of a briefing is what Im talking about, not just the frequency-course-minimums-missed briefing. For more on briefing yourself for the approach, see Tom Turners piece, appropriately enough titled “Briefing The Approach,” in last months issue,

Get all that down and you may never encounter a dangerous approach, anywhere.

Frank Bowlin flies CRJs for a large regional airline and is an in-dependent CFI in Watsonville, Calif.