Landings are typically the pilot’s biggest challenge, presenting great frustration when we screw them up even as recognition of doing it right is as rare as $2.00/gallon avgas. Apparently, the act of returning to terra firma is one we simply can’t seem to master consistently. One of the reasons is each day’s conditions are different from the previous flights, and applying what we remember from them—if anything—won’t always work. Another reason is the pilot may not have enough experience to know how to gauge conditions and modify the pattern and approach to compensate for today’s conditions.

288

At the same time, we often find ourselves making loud, firm “arrivals” instead of the smooth landings we’ve pulled off many times before and so earnestly seek. Fortunately, there’s no real secret to making good landings. If yours suck so badly the guys at the local maintenance shop are ordering a new car each time you go out for some closed-pattern work, here are five tips you can use to make sure they’ll no longer won’t get rich off your landings.

Planning

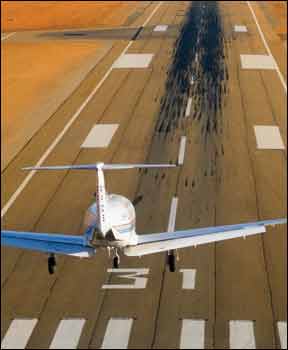

Yes, it’s a cliché that “a good landing comes after a good approach,” but it’s also true. In fact, the task of pulling off a good landing begins a few miles out from the airport, when the pilot (that’s you) sizes up the airport, its runways, the weather—especially the wind—and the traffic to plan a safe, appropriate pattern entry.

By the time a pilot worries about his or her landings, they have a few of them under their belt and should know what to do and when. Problems crop up from distractions: other traffic, the CFI intentionally creating havoc, radio calls, etc. But if a good, sound plan is developed before and during the pattern entry, even the worst distractions won’t materially affect your landing.

Planning, of course, is more than just picking which runway to use. It also involves choosing where on the runway to touch down, what to do if you need to abort the landing when another pilot taxies onto it for takeoff and what to do about the wind.

In fact, planning for the wind is one of the most important “head-work” things you can do to improve your landings. Think about the different power settings and airplane configuration changes you’ll need to make on a calm wind day versus when there’s 20 knots howling down the centerline. Think also about when and how steeply to turn in the pattern, whether you’ll need to carry some extra power down final and how far you really want to extend that downwind leg. The results can mean the difference between an easy arrival and doing a lot more work than necessary.

Configuration

Speaking of configuration changes, no matter what kind of airplane is being flown, there are specific things you need to do to ensure it’s ready to land. Deploying wing flaps is a prime example, but there’s usually more to do than simply dropping the barn doors.

Landing gear—almost as great a drag producer as wing flaps—comes to mind, as does care and feeding of the engine by ensuring carb heat is applied and the fuel boost pump is on. Don’t forget to set the pitch trim and…well, the list can get fairly long, depending on the airplane’s complexity. The key is to get the airplane configured early, let the changes result in the descent rate and airspeed we want and allow the airplane to find its equilibrium again.

I was taught—and it’s worked well for me ever since—to start configuring the airplane while on downwind and abeam the runway numbers, which is where I wanted to touch down. The changes began with a power reduction, Then, as the airplane decelerated into the white arc, deploying the first “notch” of flaps, usually 10 degrees. Re-setting the pitch trim and letting the airplane slow down and descend were next. By the time I reached the 45-degree point and was ready to turn base, I had a pretty good idea if the power reduction was too great and whether the wind was as strong as anticipated.

After turning base, it might be time to add another notch of flaps; it might not, again depending on the wind. Same with adding or removing a couple of hundred rpm.

By the time you are well-established on final, though, the airplane should be in its landing configuration: gear and flaps fully down, power set, the remainder of the pre-landing checklist complete. Other than perhaps adjusting pitch trim or making slight adjustments with power, you shouldn’t be futzing with any of the secondary controls and only manipulating the primary ones to keep the airplane descending, on-airspeed, to the runway.

A final thought on configuration changes: If you’re making them on short final, that’s a clear sign you should consider going around and trying again.

Airspeed Control

Controlling your airspeed in the pattern and all the way into the flare is key. The simple fact is unless you’re on-speed and at altitude over the runway, there’s little chance the landing will work out the way you want it.

As with almost everything else in making good landings, airspeed control begins well before entering the pattern, when you reduce power to descend to the proper altitude. It continues through the downwind leg, as you ensure you’re in the white arc and can safely extend the wing flaps, and continues through the base leg as you gauge your altitude, distance from the runway and plan your turn to final. Most important, however, is establishing and maintaining the desired speed when crossing the threshold and entering the landing flare.

Years ago, when I bought my current airplane, the insurance company wanted me to have a mere two hours of dual in a similar one before they’d cover me. I found a willing instructor and airplane, and off we went. One of the things I took away from that session was the CFI’s admonition to be at 70 KIAS “over the fence” when approaching the runway. In my airplane, that’s worked out well, although I do subtract a knot or two when light and add a couple when heavy.

Except for the actual speed, the same thing is true for the airplane you fly. Whatever speed it is you want to fly over the “fence,” it’s going to be the same for each and every landing. Yes, there are optimal speeds for downwind, base and turning final, but when the rubber starts getting close to meeting the runway, you really, really need to be on-speed.

When contemplating why you’re not making consistently good landings, start with the airspeed at which you’re flying when approaching the runway. There’s simply no substitute for airspeed control. Period.

Sight Picture

Understanding what you should be seeing out the windscreen when on final approach is a huge part of making successful landings. If the intended touchdown spot isn’t remaining fixed in the windscreen while sliding down the final, you need to do whatever’s necessary—pitch up and add some power, or relax back pressure and reduce power—to put it back where you want it and keep it there. But sight pictures apply elsewhere in the pattern, also.

Visually aligning the airplane with the runway begins during the pattern entry phase, when the FAA-standard 45-degree pattern entry is gauged to result in the airplane being laterally displaced the appropriate distance from the runway. In fact, this is a point at which many sins are committed.

Put the airplane too close to the runway on downwind, and there won’t be an opportunity for a real base leg. Too far away and the descent rate you’re planning will need to be reduced or you’ll come up short.

Establishing and maintaining the proper sight picture also applies throughout the remainder of the pattern, just not in the way you might have come to expect. Instead of looking through the windscreen to gauge your alignment with and height above the runway, you need to look out the side windows, too.

Directional Control

One final area too often omitted from landing practice is the need to establish and maintain directional control in the flare and through the rollout. Once the nose starts to come up and power is reduced in the flare, physics takes over and demands we react if the airplane is going to continue to be aligned with the runway.

Meanwhile, deceleration and the resulting more-pronounced wind effects, if any, mean we’ll need to adjust any corrections we’ve applied, perhaps to full rudder or aileron deflection to keep things upright and aligned.

Which control to use and in which direction is beyond this article’s scope, but the key takeaway is the need to establish and positively maintain directional control. Reading through each month’s accidents and incidents is sobering when one realizes almost all runway-loss-of-control mishaps involve failure to keep the airplane aligned with the landing surface.

All Together Now

Consistently making good landings isn’t rocket surgery. The biggest challenge is recognizing when and what to do differently when conditions demand. Most of the time, doing it the same way you’ve been trained will pay off as you become more experienced. But, as it is with trying to get to Carnegie Hall, don’t forget to practice.

If you still aren’t getting the results you want, grab a more-experienced friend or grizzled CFI. They might spot things you and others have missed. Above it all, strive for the pride in perfection a consistent series of good landings will instill. You’ll do fine.