Flight under instrument flight rules (IFR) is largely procedural. Theres little room or tolerance for zany spontaneity so, if you love surprises, look elsewhere. But although we fly by the book, when the plot thickens, we do in fact have options (although theyre more like regulatory provisions) for choosing a different ending. Usually, the thickening agent affecting our best-laid plans is weather-related. Before we can exercise that freedom of choice, however, IFR pilots must fulfill certain obligations. Some of these rules are similar to those for VFR flight, such as how much fuel we should have on board. Some, however, go literally a step beyond, such as the requirement for specifying an alternate destination (as well as hopefully having some rough plan for getting there). The idea of even thinking of an 288 alternate airport may be foreign for some newly anointed VFR pilots, but in the IFR world, its a well-known commodity. Its nothing other than simply having a Plan B. In Canada, in fact, there is virtually no such thing as flying under instrument flight rules without an alternate airport, period-at least not without special dispensation from the Minister of Transportation. So yes, IFR flight to some extent allows us the chance, at least to some degree, to punch through certain kinds of weather. But there are limits. When You Need An Alternate At first glance, the Federal Aviation Regulations covering the choice and specification of alternative destinations can seem convoluted and hard to remember. Actually, its not exactly as easy as falling off a log, but it isnt really that bad. Here is one way to remember the rules for IFR alternates and minimums: The first cornerstone or anchor memory aid is, literally, as simple as one-two-three. They represent three “ifs”: the “one” refers to hours of time; the “two” is for ceiling in thousands of feet; and the “three” represents visibility in statute miles. Think of it like the sequence of factors for considering missed approaches: how long, how low and how far. To paraphrase this regulation, if between one hour before and one hour after the expected arrival time at your primary destination, the forecast ceiling is at least 2000 feet and the visibility is at least three statute miles-note thats an “and” not an “or”-you dont need to specify an alternate. Otherwise, dig out the charts. The second anchor point, one which follows along nicely, is the number 45. (1-2-3, and then 4-5…get it?) This is the rule saying if you dont need an alternate, you must have enough fuel to fly another 45 minutes past your destination, at normal cruise. Its your job to calculate your likely en route time given forecast winds aloft, intended power settings and true airspeed. Id advise throwing in another half hour for unexpected vectors and other delays. The other part of this second part, if you will, says that if the weather does dictate filing an alternate, you must have enough gas to fly to the primary destination, fly to your alternate, then on top of that fly 45 minutes more, again at normal cruise power. One more time: These are FAA minimums. If I were you, Id fudge those up a bit in your own favor. Of course for those new to IFR-anything, I should note here that pilots can certainly fly under instrument flight rules to a grass strip with no instrument approach whatsoever. In most cases if your destination doesnt have an instrument approach, the ceiling and visibility must be good enough for you to proceed VFR from the so-called minimum en route altitude, or MEA. In cases where youre flying in a radar environment, ATC may be able to descend you down to whats called a minimum vectoring altitude, which can be lower. Usually only the controller will know what altitude that is, for whichever sector of airspace youre flying through at that time. Alternate Minimums The 1-2-3 rule covers the primary destination, but the regulations go a little further than this: The next one covers your alternate, as far as something known as “alternate minimums.” This one can be remembered as the “602 or 802” rule. It says that as far as your alternate goes, if specific alternate minimums are not published for that airport (more on this in a minute), and if between an hour before and an hour after you expect to get there (same as the 1-2-3 rule), the airport is expected to have at least a 600-foot ceiling and two miles visibility, you can use it if and only if it has a precision approach procedure. If it has only a non-precision approach procedure, everything stays the same except the 600-foot minimum ceiling goes up to 800 feet. These are the so-called standard alternate minimums. Some airports, because of terrain or obstructions, have different ones. Jeppesen includes them right on the approach plates for each airport whether theyre standard or not (usually on the back or “airport layout” side of just the first approach plate when an airport has more than one), but youll have to look elsewhere for this information if youre using approach plates produced by the gummint. The one other very important thing to note here is that these alternate minimums arent for actually landing at your alternate; theyre just for your advance planning option in case you need to divert there. If you do “go missed” at your chosen primary destination and you then fly towards your alternate, you simply pull out the approach plate for your alternate airport (or much better and much wiser, you already had it out ready to go, underneath your first ones) and fly according to the published minimums for that airport, just like you did with the first one. That sometimes comes as an “Oh, really?” revelation to those first learning about IFR procedures. I know it was, for me, way back when. Picking An Alternate So much for the FAA rules (See, that wasnt so bad, was it?), but now we come to the realm of judgment and strategy. How do you know which alternate will work out and which wont? Of course, as in-flight data trickles down to general aviation cockpits everywhere, all of it eventually will be right in front of us. But if you arent an early adopter (or even a middle level one) and you dont have up-to-the minute METAR reports on display in the cockpit, Flight Watch certainly will be able to provide them to you. Itll just take a bit longer. Also, you can never be sure those forecasts will come true, so never assume the destination weather and winds will match those for which you have so carefully planned. But what else can you do about it? As a general rule, when youre fishing for a good alternate, pick something

One caveat about large airports: They can be busy, so plan for enough “extra, extra fuel” to cover delays or simply being vectored hither and yon before you get to land there. (Again, its that fudge factor.) As far as weather surprises go, until there are National Weather Service metrics for unexpected drops in ceilings and visibility, compared to the current forecast, also given right along with each updated METAR-and dont hold your breath waiting for it-the one thing you can do to get a jump on changes is compare them yourself as you go, listening for AWOS and ATIS broadcasts along the way.

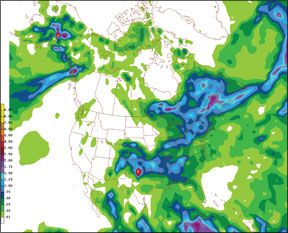

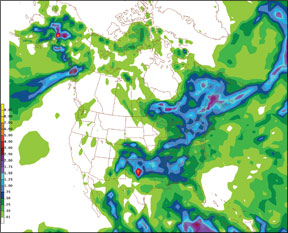

However, it doesnt require any work at all to know that the odds of needing that alternate will go way up when there are widespread low ceilings and visibilities; if several reporting points are updating their sequence reports with “specials” (or the terminal aerodrome forecasts are being amended), watch out! The other time-honored way that you can get updated information of course is, again, via Flight Watch.

Finally, and in case you were wondering, there are no FAA rules for an “alternate alternate” in case the weather really goes down the tubes and you cant get into either your destination or your alternate, even after factoring in that conservative 1-2-3 at your primary. Sort of gives new definition to “on your own,” doesnt it?

Managing Alternatives

Where I fly in the mid-Atlantic region, the average price of 100LL has reached over four dollars a gallon. (I dont really even ask anymore.) However, when youve gone missed and then cant get into your alternate because of worsening weather, the cost for having taken on extra fuel probably wont even register on your radar screen of unwelcome annoyances.

And, on the subject of worsening weather and having to go even further away to get back to Earth, in populated areas such as mine, that 45 minutes I mentioned earlier is probably getting close to having enough extra fuel. But if you fly west of the Mississippi, or anywhere else where airports are few and further between, you might want to make that two hours of extra fuel. Thats right-I said two hours.

There are two motivations for planning IFR flights in such exhausting detail like this. Truth be told, IFR flight planning is actually easier than VFR planning in a way, because its so procedural, and because many of the airspace permissions are already taken care of, so to speak. The first motivation is safety, of course.

The minimums and backup planning Ive described exist to keep you and your passengers as far away as possible from having no options left. The second motivation is a three-letter acronym: CYA. If something ever does go amiss on a flight, you can be sure that the FAA will be looking to see how well you had planned and prepared for it.

At the end of the day, choosing and filing an alternate airport isnt rocket science; the most suitable one may be the nearest runway with an ILS. As these pages have tried to hammer home on many occasions, the need for an alternate landing facility shouldnt come as a surprise: Good airmanship requires monitoring the flights progress, the weather and fuel. The only time any of this should be a surprise is when the guy in front of you forgets to lower his gear, closing the airport.

Jeff Pardo is a freelance writer and editor who holds a Commercial certificate for airplanes, helicopters and sailplanes.