One of the first things instrument pilots learn during their training to fly approaches is reading the fine print, the various notes that may accompany a published procedure. It’s a classic case of the large print holding great promise while the small print dashes any lingering hopes. Perhaps most ubiquitous is the NoPT admonition that a procedure turn is not authorized when flying to the final approach fix on certain segments.

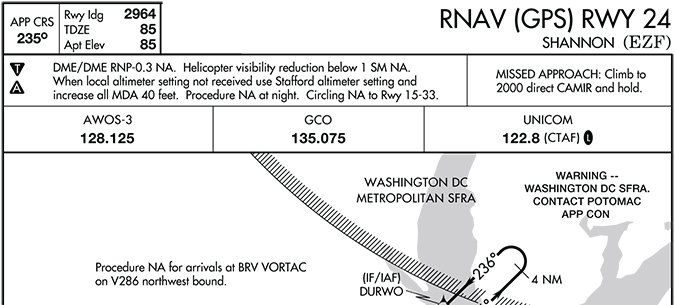

One that’s been tripping up a lot of operators lately, however, is the seeming proliferation of notes advising an approach procedure is not authorized at night. The approach is legal during the day, the runway has lights, so what’s the problem? Did the airport not pay their electric bill? Not exactly. In fact, finding an approach NA at night is becoming increasingly too common. What’s going on?

Penetration

While each airport and approach can be different, one of the things going on is rather simple, and has little to do with lights or electric bills. Instead, it’s likely a tree or other obstruction has penetrated some portion of the approach’s visual area surface, a component of instrument approach approval and design. The visual area surface is an area beginning 200 feet before the runway threshold and rising one foot for every 20 feet it extends laterally. As such, it’s known as the 20:1 slope.

The 20:1 slope is a longstanding part of FAA policy regarding how approach procedures are established and exists to help prevent aircraft executing the approach from colliding with obstacles, day or night. According to AOPA, that policy has, over time, allowed modifications to the approach procedure—such as raising the minimum visibility—when obstructions penetrate the slope.

Again according to AOPA, “The terminal procedures (TERPS) design criteria changed in 2002 to require penetrations to be marked and/or lit so as to make them more conspicuous to pilots, or a Notam issued for the procedure that would not authorize the approach at night. Airport compliance and oversight was poor during this time, with the FAA placing little emphasis on enforcement.”

The FAA faced a choice: Either raise the minimums for approaches to numerous airports around the country or figure out a way to make the problem go away. One way to make the problem go away was to either eliminate the obstruction—cut down the trees—or illuminate it for night approaches. The presumption apparently is the obstacle easily can be spotted during daytime and avoided.

Instead, the FAA opted for a third choice, to issue a memo pencil-whipping the problem and kicking the can down the road. Things more or less went back to normal. The 20:1 slope still existed in the TERPS and FAA policy; it just wasn’t being enforced by raising minimums. That changed in 2010, when the pencil-whipping memo was canceled and, in 2012, TERPS criteria were modified to make this more of a deal by enforcing the requirement to either eliminate the obstacle, illuminate the obstacle or Notam the procedure as not authorized at night.

Evolution

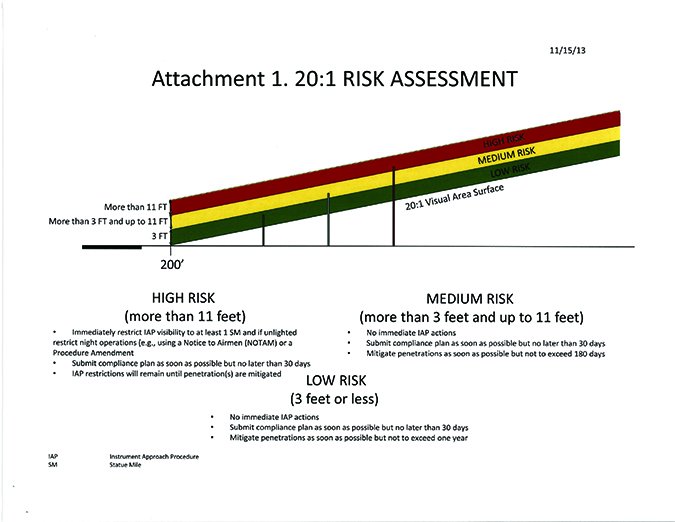

By the beginning of 2014, the FAA evolved a new, interim policy on 20:1 slope penetrations embodied in the image above. Essentially, any penetrations were to be assessed for the risk they posed and appropriate action determined based on that assessment. The sidebar above goes into greater detail.

The 2014 interim guidance expired at the beginning of 2016, as it was designed to do, and a new policy was put into place. The new policy retains the low/medium/high risk assessments and mitigation requirements, but also enlists an existing organization within the agency—the FAA Flight Standards Procedure Review Board (PRB)—to consider individual airport/approach situations. Depending on what the PRB finds with respect to a specific airport/approach/obstacle, it can issue a waiver or attempt one of the mitigation strategies.

Moving forward to 2018—the new policy put into effect in 2016 also an interim one—it’s not likely this problem will go away anytime soon. Ultimately, and as AOPA notes, “Any solution that would allow an obstacle to permanently penetrate the 20:1 is problematic from various FAA policy requirements and from the safety standpoint.”

What to Do

So, presume for the moment the 20:1 slope at your home plate is penetrated by an obstacle and the only approach is NA at night. What can you do to help resolve this, short of topping off your chainsaw and going for a hike? “Not much” is the quick answer.

Keep in mind this situation has evolved over several years, and it’s likely to take some time before it’s resolved. At its roots, it is a result of the FAA not having the authority to force removal of an offending obstacle. In general, the FAA has little to no ability to force actions when considering structures and obstacles not on airport property. Instead, the agency’s primary tools for dealing with a challenge of this sort are the ones it’s already using: short-term Notams taking approach procedures out of service and other work-arounds.

At the local level, it wouldn’t hurt to educate yourself and other operators on what and where the offending obstacle is. It’s likely your friendly local airport operator can give you chapter and verse on the situation, plus an estimate of when it will be resolved, if ever. You can also try shaming the offending landowner into removing or reducing the obstacle, but that can get into ugly local politics very quickly.

Also productive at the local level might be attempting to get another approach procedure approved. That may be a possibility if the airport has intersecting runways but may require capital investment the airport operator is unwilling to make. An approach from the opposite direction also might be possible, but there’s probably a reason there isn’t one established already.

What Not To Do

When it comes to planning your flight operations, some rather obvious additional mitigations to this problem come to mind. First and most obvious is to plan your arrivals during the daytime. When it comes to determining when day ends and night begins, refer to the FAR definitions, local sunset/sunrise and the time when ATC clears you for the approach. Have a solid-gold divert airport available if headwinds conspire against you and the weather won’t allow a visual approach.

Under no circumstances should you attempt to scud-run to the airport by, for example, reporting to ATC you’re in VMC at some point outside the final approach fix and canceling IFR, then motoring off down the approach anyway. Bad idea. This problem wasn’t created overnight, so to speak, and it will take time to resolve. The best solutions always do.