Since he was a youngster helping his father in the family business, Andy Patrick of SP Aircraft out of Boise, Idaho, has retrieved and salvaged aircraft. The workload varies. In a slow year, there may be a half-dozen aircraft to recover. In one particularly busy recent year, there were 24. There’s no real way to predict a given year’s activity.

I spend a lot of my flying in the Idaho backcountry, where there are a lot of challenging but worthwhile airstrips. But it’s not a forgiving environment since go-arounds can be problematic and density altitude means pilots may not be accustomed to the reduced performance. After decades in the business, Patrick has a lot of lived experience seeing a wide variety of crashed planes, especially in the backcountry. As a window into answering the eternal question “Why do pilots crash?” I felt his insights would be valuable.

Recognizing this, I asked if there was any one particular lesson he could pass on. “Yeah,” he said. “Don’t crash your airplane. The majority are human-caused, and even when there is a mechanical issue at the root, the human factor is what generally turns a mechanical failure into a crash site.”

Telling The Story

In response to my question, he had a hard time narrowing down the most common modes of failure, because in his experience, the causes run the gamut. His observation reminded me of something Tolstoy wrote, that “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” According to Patrick, the same is true of aviation.

“Successful flights all have the same outcome, but every aircraft crash site can tell a unique story story of aviation failure,” he told me. “It is never any one thing; it is always a combination. Even when the cause is fuel exhaustion, there is always a unique reason that the pilot either failed to get enough fuel or forgot to switch tanks.”

“The more you learn about the particulars, the more you realize there are often complicated personal and emotional factors involved that don’t always make it into the NTSB reports.”

For example, why would any competent pilot fly into a thunderstorm? We all know better and know why we should not do it. But at the same time, pilots often have a need to get somewhere that compels them to make one or maybe a series of bad decisions. Patrick’s observation: “It is rarely any one decision that leads to a crash.”

Weather is often a factor, either low visibility or deteriorating weather conditions. In some of the more high-energy accidents, planes entered thunderstorms horizontal and exited them vertical. Sometimes they were still in one piece, but just as often, they were in several. Needless to say, Patrick also advises pilots not to fly into thunderstorms.

Backcountry Blues

Much of Patrick’s business skews to backcountry crash sites, due to the relative ease of on-airport recovery versus the more complex difficulties of recovering planes from remote sites. “We are usually not called if a plane slides off the end of a local runway, because it usually doesn’t require any special skills or experience. A local can just put it on a trailer and haul it to the nearest hangar.” When aircraft are significantly off-field, or in one of Idaho’s many backcountry strips where a helicopter is often required to recover the plane, his company more frequently gets the call.

Due to his aircraft recovery job and a long family history of flying Idaho’s backcountry commercially, Patrick has both flown into nearly every backcountry strip in Idaho and removed several planes from each of them. Of those crashes, Patrick’s view was there seemed to be some common themes. Inexperience, density altitude and a tendency to show off topped his list.

For example, Patrick noted that Johnson Creek is a relatively easy airstrip for a veteran backcountry pilot, but it is intimidating to land there the first time and there is often a crowd of onlookers judging the action. Curiously, Johnson Creek seems to have a disproportionate problem with crashes.

Patrick thinks one of the biggest problems that inexperienced pilots have is continuing to try to land when going around is maybe a better choice. “A lot of crashes would have been avoided if the pilot had just chosen to go around and try again,” said Patrick. He pointed out that even the most difficult strips in Idaho, with a few exceptions, have go-around options right up to the point of reaching their particular abort points. “You need to know where your abort point is and not hesitate to break off or go around when you reach it,” said Patrick.

Airframes and energy

Patrick also had some observations about airframes and survivability. “It is amazing how much energy a Mooney airframe can take compared to a fabric-covered Cub,” he said, “but you can still have a fatal crash in a Mooney and survive a crash in a Cub. Composites don’t seem to be as strong as metal, but it really depends on how hard and fast you hit.” Patrick pointed out that many composite aircraft have parachutes that vastly improve overall survivability because they significantly reduced the energy of the crash.

Survivability has more to do with the energy of the crash than it has to do with the airframe itself, so if you do have to crash, Patrick prefers a good low-speed crash in a well-equipped aircraft. It is best for business, and there’s lots to salvage without next-of-kin involved. High-energy crashes don’t leave much to salvage. “I remember, when I was about 10 years old, finding a wedding ring at a crash site and realizing someone had died here. It makes you think, and changes how you fly, but it is part of the business you wish you didn’t have to deal with.”

The training Factor

When Patrick gets a summertime callout to one of Idaho’s more popular backcountry strips, it is often for a predictable reason: a pilot with low experience flying on a day with high density altitude. Not to be too cavalier about it, but the sad truth of aircraft salvage is that poor pilot training is good for business.

Patrick sees lack of proficiency as a common root cause of many crashes. “Pilots are all humans, and people are often lazy. They prefer the easy route whenever possible.” He suggests that pilots challenge themselves with harder training. Instead of going to the same instructor for a flight review or instrument proficiency check, seek out instructors who have hard, rather than easy reputations.

He also emphasized that pilots should think about shoring up the weakest link in their flight skills. “If you fly IFR with an autopilot or GPS, turn it off and do some flights without it to make sure your basic flying skills are still there.”

Stay In your lane

Patrick had some final words of advice. He noted that flying airplanes carries risk, but so does driving a car, riding a motorcycle, using a four-wheeler or bicycling. “If you are out having fun, make sure you are having fun. Try to avoid getting yourself into stressful situations that may be beyond your skills. Don’t let stress and emotional circumstances push you into making bad aviation decisions.

“And finally, if you do get into a stressful situation, don’t crash.”

Pilot Related Accident Causes

The two basic kinds of accidents-mechanicals and pilot-related mishaps-both have something in common: pilots often can prevent them. Either we conduct a thorough preflight inspection or we don’t. Either we carry enough gas to get to our destination or we don’t. Rinse, repeat.

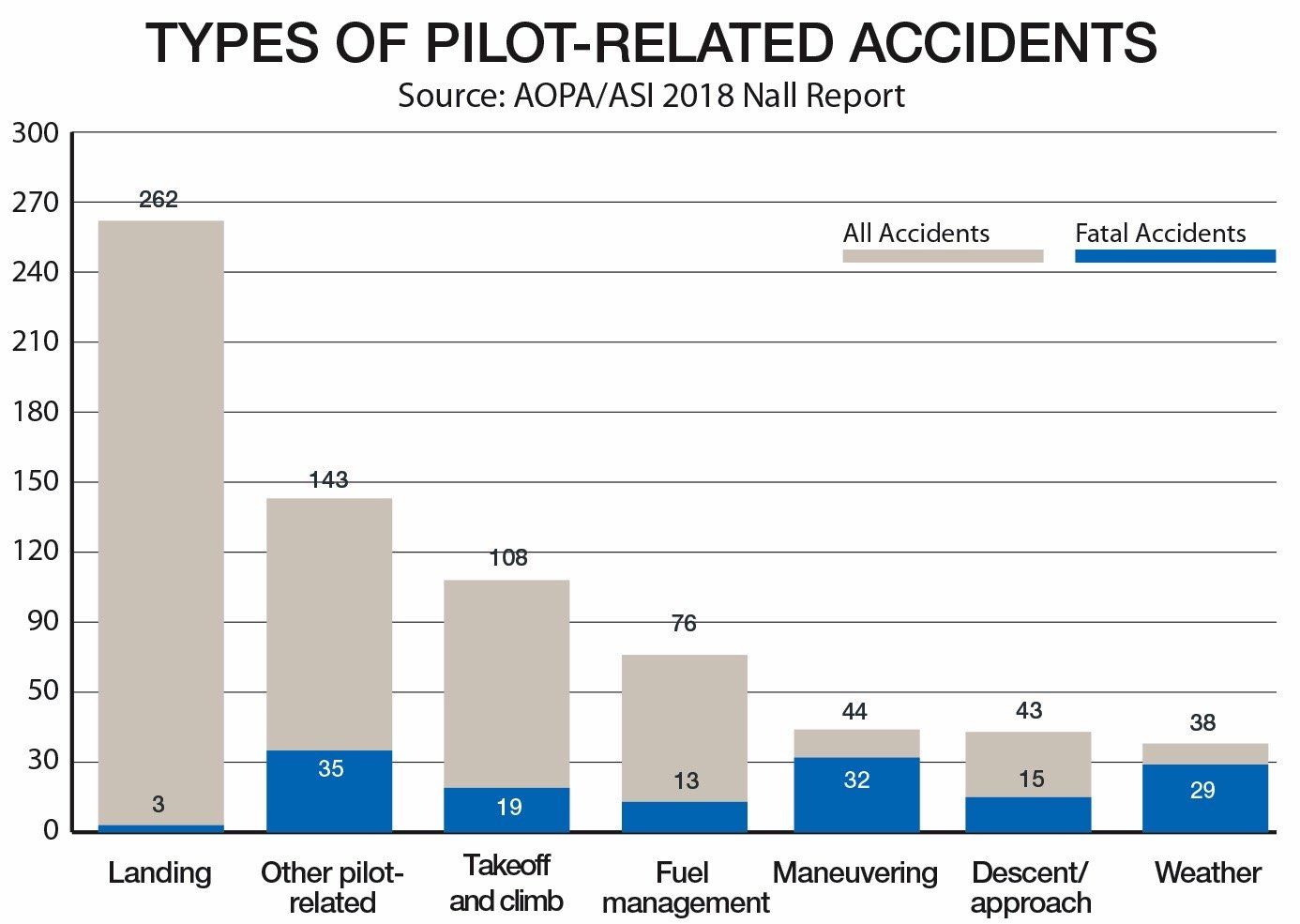

The broad categories of pilot-related accidents the AOPA Air Safety Institute (AOPA/ASI) has compiled from NTSB data for 2015 in its 2018 Nall Report are shown at top right. The good news is that the lethality of the top four mishap types depicted in the top chart at right isn’t as great as their hype. The bad news is that other pilot-related causes can have dire consequences, too.

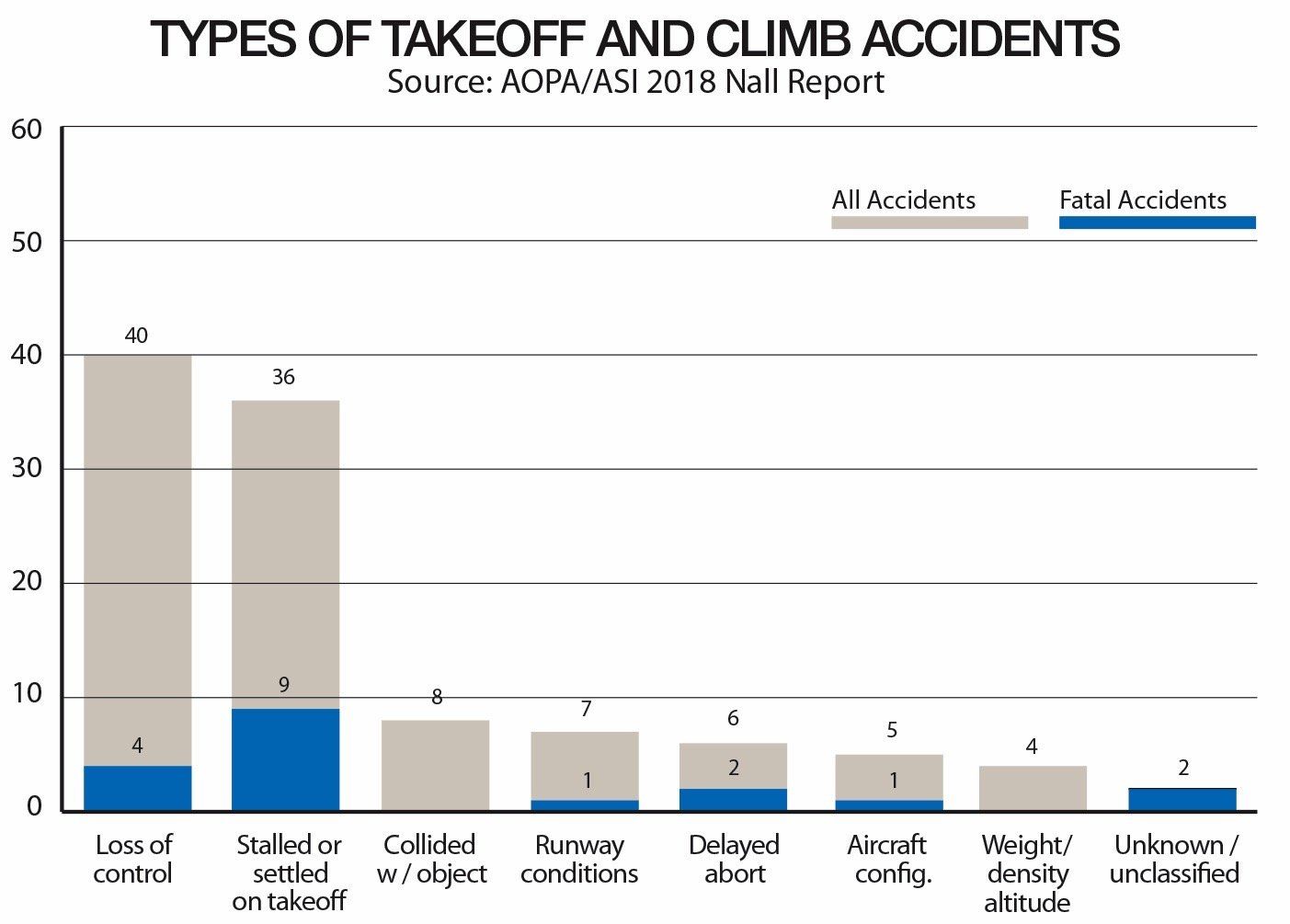

The chart at bottom right zooms in on takeoff and climb accidents where our old “favorite” loss of control rears its head. In this data, however, the numbers point to losing control on the runway during a takeoff or landing attempt, rather than while maneuvering, the most lethal way to lose control.

Pilots can help minimize these kinds of accidents by understanding when, why and how they most often occur and exercising good judgment when planning and making their go/no-go decisions. – JB

Go Around Early, Go Around Often

Andy Patrick’s perspective on go-arounds highlights a mindset pilots have from time to time: “There’s a runway in front of or under me and I’ve got to land on it.” Idaho’s backcountry highlights the problems pilots can have when they stray from their flatland runways, but the bottom line is few of us actively plan for a go-around during a normal approach.

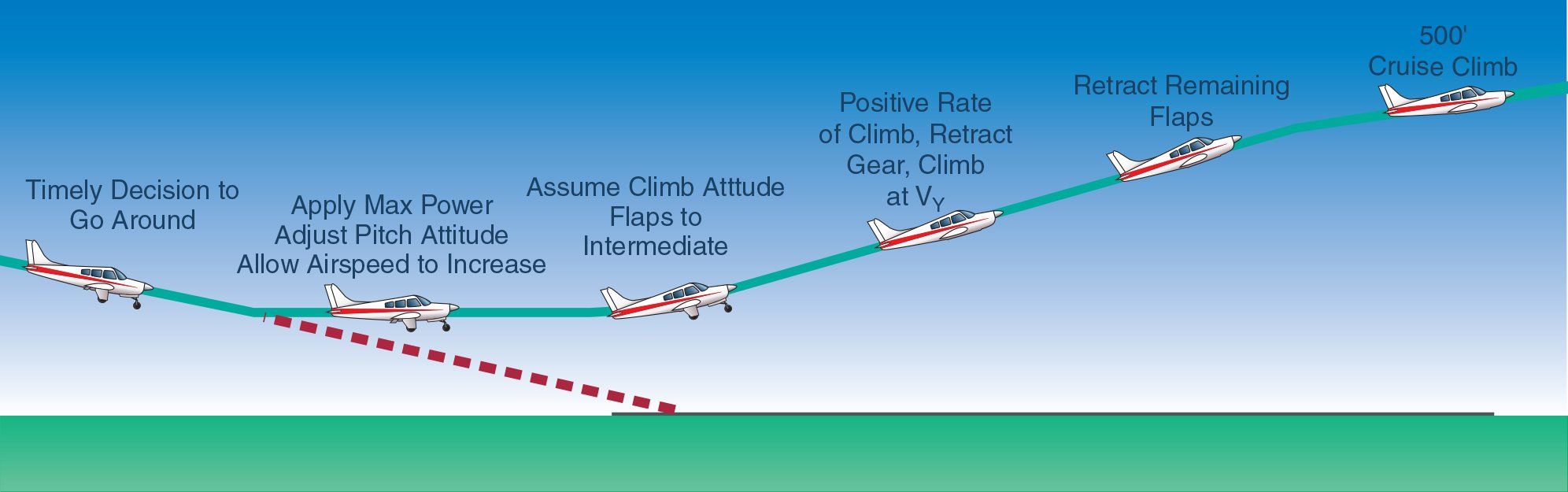

According to the FAA’s Airplane

FlyingHandbook (FAA-H-8083-3B), go-arounds are called for in “[s]ituations such as air traffic control (ATC) requirements, unexpected appearance of hazards on the runway, overtaking another airplane, wind shear, wake turbulence, mechanical failure, and/or an unstable approach.” To which we probably should add stable but poorly planned approaches, less-than-planned performance and aircraft misconfiguration as reasons we may want to go around. Putting aside the actual airmanship involved in going around, the decision to go around is akin to the old stereotype of elections in Chicago, Ill.: Vote early, vote often. Don’t delay the go-around, and feel free to use it as often as you like.

When we decide to go around can be more important than the decision itself. That’s especially true in backcountry operations, when you may not have enough performance to outclimb the uphill slope that serves as a landing strip, and must turn or collide with terrain. Even at your home plate, you need to have a plan. When the student pilot pulls out in front of you to take off, what will you do? When will you do it? You’ll initiate the go-around once the other aircraft takes the runway, and you’ll fly to whichever side of the runway affords you the best view of the offender. – JB

Finding Proficiency

Unless you fly for a living, it’s likely the most proficient you’ve ever been was for your most recent checkride. For some of us, that was a long time ago-maybe we should do something about that.

A good place to start would be with the article beginning on page 16, regarding safety pilots. Not only can flying with the right person help both of you gain and maintain proficiency, but you both likely will learn a few things from each other along the way. But having a flying partner is less important than getting out and flying.

Of course, just going out to bore holes doesn’t necessarily keep us proficient. If you have an instrument rating you’re trying to keep current, you may have a small group of fellow pilots you fly with from time to time, with one of you under the hood. You may also have a friend who’s a flight instructor and fly with them often.

Even without a “buddy system” of some kind, you can take real steps toward maintaining proficiency all by yourself. When was the last time you did any ground-reference maneuvers? Flew your touch-and-goes to a crosswind runway? Practiced short-field operations? Stalls or slow flight? Simulated an engine failure lately?

The point is that something the pilot did or didn’t do often is the reason an airplane crashes. If you haven’t practiced lately, how do you know you’re doing it right? – JB

Excellent advice, insightful observations.

One critical point that is not directly mentioned: Takeoff and initial climb represents a VERY tiny slice of time in nearly every flight. At best we’re talking about 2 minutes from throttle to above pattern altitude and a couple of miles from the airport. Yet this tiny slice of time had 19 fatalities out of 108 accidents as shown in the 2018 NALL bar chart labeled “Types of Pilot-related accidents”. What’s the average time of a flight from start to finish? My log books show that in over 4100 hours flying time the average is between 1 and 2 hours. Descent, approach, and landing may take 10-12 minutes or so. Those phases of flight had 262 total accidents and just 3 fatalities in the landing phase lasting maybe 30 seconds, and 43 accidents with 15 fatalities in the approach and descent phase that might last 5-10 minutes. There’s no question that the takeoff and initial climb phase of flight is, hands down, the most risky operation we do. For a flight of just 1.25 hours (75 minutes total) the odds of an accident where fatalities occur are higher than most of the other phases combined. And what is the underlying contributor to both crashes and fatalities? Look to “System Malfunction – Powerplant” as the ugly demon in the aircraft. Our best defense is to thoroughly pre-brief the takeoff, be spring loaded to chop the power if on the ground or know exactly where we’ll put the aircraft if the engine misbehaves after liftoff.

Know your airfield and surroundings, know your aircraft performance, know your “turn back ‘ altitude. Don’t violate any of those limits.