Regular readers of this journal are familiar with the series of articles I’ve written and advice I’ve given on the art and science of risk management. By now, you’re probably curious as to whether I actually use and implement the information and practices I recommend in my own aviating, or whether I’m merely speculating from some safe, lofty journalistic perch.

288

The answer is that I could not simply follow the latter approach and, yes, I do follow my own advice. With that in mind, I thought it was probably time to share some of these experiences, since they perfectly illustrate the practical risk management challenges we all face as general aviation pilots.

What’s Your Profile?

We all fly general aviation airplanes for a variety of purposes. You may be interested in just flying locally in a simple airplane for pleasure. Some of you may be taking training and building experience for a professional pilot career. Many pilots actually use general aviation airplanes for personal and business travel, and I’m squarely in that camp. In fact, the 1980 Beech V35B Bonanza that my consulting and publishing company operates is solely used for business transportation. If that need disappears, so will the airplane. My operational profile may be changing soon, but I’ll use my historic profile as the template for this article and the others in this series.

Since my profile is exclusively business travel, my airplane use is ruthlessly determined by the bottom line. I select the Bonanza for missions where it can compete with the airlines on reliability, schedule and even cost. Otherwise, I’ll get a business-class seat for my travels. Usually, my mission profile involves four or five multi-stop trips a year that often go to locations with poor or no airline service. They often keep me away from home for a month and include as many as 20 stops.

You should also know that I’m not a gadget-hound and the bottom line governs how I equip the Bonanza. The photo at below left shows that the airplane still has the avionics it was born with, except for the portable Garmin 396 on the yoke. It all works, but most of it belongs in a museum. I must be one of the few pilots flying today not using a tablet in the cockpit, but in terms of safety/utility and operational risk management, what you see is all I need.

Strategic Risk Management

You must view risk management strategically because your flight operations are often affected by “big picture items” and not just the circumstances of a specific planned flight. In considering these strategic risk factors, you can use the same PAVE acronym that most of us are familiar with. The acronym stands for Pilot, Aircraft, EnVironment and External pressures. Let’s look at some examples that are strategic in nature, and how I answered the questions they pose.

Pilot: Have you been maintaining currency and proficiency during the months before a flight? For example, I don’t have many business flights during winter months. That’s when I’m completing client projects, finishing writing a novel or other book, or completing other work. There are no conventions for my aviation business activities in the winter months, so I generally have no need to fly.

Nevertheless, I create a proficiency profile that ensures that I’m flying enough to maintain critical, perishable skills, such as instrument flight and dealing with the ATC system. With the typical winter weather in the Northwest U.S., I can easily find actual IMC, so I can dispense with the inconvenience of a view-limiting device or safety pilot and experience the “real world.”

Currency and proficiency are critical, but so are pilot aeromedical issues. Adequate rest, hydration and alcohol management are part of this. So are the need for supplemental oxygen and awareness of the effects of prescription and over-the-counter drugs.

Aircraft: In a similar manner, you should anticipate maintenance and other events for your aircraft. For example, before the series of flights I’ll shortly describe, I realized the Bonanza would be coming due for an oil change during the trip. Rather than the hassle of getting that done while en route, I had the oil change done early by my local shop. I also carefully monitored the aircraft systems during my proficiency flights to ensure that they were operating normally. Systems such as the autopilot are especially critical.

Environment: This is, of course, a huge factor both strategically and tactically. The weather, terrain, airports and airspace are crucial areas that generate risk and require management. Of these, weather is the most variable and my strategic planning horizon for weather risks generally begins about 10 days before a planned flight. That’s when I watch the 10-day rolling forecast and start assessing whether I need to make schedule changes. I’m always seeking to mitigate risk and I follow the TEAM acronym, or as I re-order the letters, TEMA. That’s Transfer, Eliminate, Mitigate, Accept. If the long-term risk profile for a series of flights increases, it’s best to “transfer” risk (to the airlines) or “eliminate” risk (by cancelling or rescheduling meetings) early in the game.

External Pressures: I’ve discussed these already, but I will emphasize that the key to managing these is schedule flexibility. The three “tiers” of external pressures that I previously mentioned allows me to create flexible travel itineraries so that I can reduce or eliminate external pressures.

Tactical risk management

I’ve discussed tactical risk management procedures in earlier articles, so I won’t dwell on these here. It’s always a three-step process—identify, assess, mitigate—that’s applied during the planning immediately before a flight and continuously during it.

If I do a good job of strategic risk management—choosing an appropriate route, day and time—it generally makes the tactical risk management much easier. I always keep in mind that I’m flying a non-ice-protected, single-piston-engine aircraft. While it is reliable and its IFR capability improves dispatch and schedule reliability, it does not provide the “near all-weather capability” of turbine equipment, especially in the Intermountain U.S. West. That’s enough strategy and tactics. It’s time to roll up our sleeves and get into the mission.

288

A Typical Mission

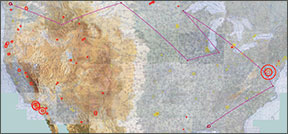

The series of flights I made just before I wrote this article were scheduled to consume an entire month and then some, from June 2 to July 3, 2013. My itinerary included 18 scheduled stops (not including refueling or RON-only stops). Of these, nine were for research purposes for a book I’m co-authoring and included such out-of-the-way places as Watford City, N.D., Keokuk, Iowa, Goshen, Ind., and Salmon, Idaho. Some of these destinations are plotted in the image above. Try scheduling an airline itinerary that would get you to these places.

Another seven stops were for actual and potential aviation clients and partners and included more familiar locations such as Duluth, Minn., Washington, D.C., and Norfolk, Va. Finally, I had two scheduled conventions to attend: the Historical Novel Society in St. Petersburg, Fla., and the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association (COPA) “Migration” in Mobile, Ala. I was a scheduled speaker at the COPA event.

I would basically circle the United States clockwise. Although I would fly between 35 and 40 hours and between 5500 and 6000 nm, there was only one day when the flying would exceed four hours. It looked like it would be a typical multi-stop itinerary that I’ve been doing multiple times a year for the last 30 years or so in a Mooney 201 and two Beech V35 Bonanzas.

The first hurdle

As departure day loomed, the weather picture was shaping up: It was typical for the Pacific Northwest. A marine layer would form and then lift, obscuring the Cascades, but otherwise creating fairly benign weather with no convection. As is true in the Northwest 12 months a year, the key question is: What about icing?

As the weather situation developed, I could see there would be a threat of icing over the Cascades on the scheduled departure day, a routine strategic risk management problem for my flight operations. There actually are many options for dealing with this kind of problem if you have schedule and route flexibility.

I have built that flexibility into my planning, thanks to my location in the extreme northwest corner of the Lower 48. Basically, all (air) roads lead generally southeast. You can go east or south before continuing southeast and the wonders of geometry and trigonometry ensure that you will not add that many miles to your trip.

So, I decided to leave a day early. My departure route options included four VFR routes and four IFR options for each of them:

Direct (over the Northern Cascades): Contrary to the picture I painted above, there are many CAVU days in the summer in the Northwest. On those days, I will just go over the top at 15,500 feet and use my portable oxygen system. If you’re IFR, ATC will clear you direct when as low as 13,000 feet. If it’s a solid undercast, I won’t do this either VFR or IFR, since the underlying terrain is rough. Hence, I rule this out on departure day.

South to Seattle, then east: This route can be negotiated VFR with an adequate ceiling or flown IFR eastbound at 9000 feet on Victor 2. Some people choose to scud run at even lower ceilings through Stevens Pass. The tactical risk for this is quite high. If IFR is not possible because of ice, I will choose another route.

“Shoot the Gorge”: This route follows the Columbia River gorge marking the boundary between Washington and Oregon. It was first pioneered at zero feet agl by Lewis and Clark. I can imagine them running their PAVE checklist to manage the risk, the external pressure being provided by the natives who hoped to collect their goods when the canoes capsized in the rapids. It can be done VFR safely with adequate ceilings, or IFR eastbound at 7000 feet, again presuming no ice.

South to southern Oregon, then east: This diversion can take you all the way to the border between Oregon and California. By going this far south, you can often find a VFR path, or you can go IFR at 9000 feet to Klamath Falls. From there, the MEAs eastbound will increase. If you’re flying from the Seattle area to Colorado, this route adds very little to your trip distance over a more direct route.

My strategic risk planning pays off. By leaving a day early, we avoid ice and I exercise the second option, following Victor 2 east from Seattle at 11,000 feet between layers. The temperature there is even above freezing. The rest of the trip to Bozeman, Mon., our first stop, is routine and in good VFR conditions as soon as we clear the Cascades.

The Second Hurdle

We arrive early enough in Bozeman to complete our research that day. Before heading to the brew pub to celebrate, I check the weather and find that the cooler moist air that we left will overtake central Montana the following afternoon. The terminal forecast calls for 3000–4000-foot ceilings, resulting in 7500–8500-foot msl bases. The freezing level forecast is about 9000 feet msl, and the MEA eastbound is 10,900 feet msl. The prog chart indicates even worse conditions the following day.

Our original plan was to stay in Bozeman two nights. We might be able to fly VFR through Bozeman Pass, which is at 5718 feet msl and surrounded by terrain at 8000 feet and higher. We might end up being surrounded by icing conditions, since Bozeman sits in a bowl.

This risk problem illustrates the issues with flying IFR/IMC in a non-ice-protected piston aircraft in the Intermountain West. It’s usually either impossible or is very limited. Since there is spotty radar coverage at the MEA, you are forced to stick to the airways, and MEAs are always higher than required for terrain clearance due to navaid reception limitations. Hardly any airways have published altitudes for GPS-equipped aircraft, which is the main reason I refuse to invest in panel-mount equipment.

This is actually a very easy strategic risk decision. Our work in Bozeman is done, so we decide to depart early the next morning. We are now two days ahead of schedule. The flight east to Watford City, N.D., is in good VFR conditions and is routine. We are now in the Great Plains, and the icing threat recedes for the rest of the trip.

We finish our research project in Watford City the same day. You have to see this place to believe it. It’s in the exact middle of America’s new energy belt, the Bakken Formation, and even on our Sunday arrival, there was activity everywhere, with temporary housing, even tents, and the aura of the Old West. Unfortunately (or maybe fortunately), there were no regular hotels or other rooms available and late in the day, we made the short flight to Bismarck for our RON.

To Be Continued…

The next day begins a new phase of our itinerary. We will be headed for Grand Forks, N.D., and points east. We will manage new hazards and risks in our pursuit of staying on or ahead of schedule. There will also be some unexpected surprises in store.

Robert Wright is a former FAA executive and President of Wright Aviation Solutions LLC. He is also a 9500-hour ATP and holds a Flight Instructor Certificate. His opinions in this article do not necessarily represent those of clients or other organizations that he represents.