By Ron Levy

For many years, the pilot in the cockpit of a general aviation aircraft has usually been the last to find out what the weather is doing. The airline pilot has always had the advantage of the company dispatch system – someone on the ground checking weather reports and forecasts, including both the big and localized radar maps and images, and just a radio call away on the company frequency. Airline pilots also had the advantage of a second (or third) crewmember to get that information on another radio while the pilot flying was able to stay on ATCs frequency.

The GA pilot has always had a serious disadvantage. The weather information available to those to whom the pilot could speak was usually either of poor quality or time-delayed. The weather radar available to controllers was never particularly good, and providing that data to pilots has always been a low priority on the controllers agenda. Controllers could give info on current local weather, but you had to get off ATCs frequency and talk to Flight Service to get a broad picture of the weather and any updated forecasts.

Thats OK in theory, but it never really worked that way in practice. You might or might not be in range of a FSS communications outlet, and even if you were, you might be sharing the frequency with other aircraft and FSSs carrying on conversations for hundreds of miles around. Often, and particularly in bad weather when you needed the information most, you might find yourself fourth in line to speak with the FSS, and ATC wanted you back on frequency within three minutes.

Even if you did get the information, weather, especially convective activity, changes so fast that you couldnt possibly stay abreast of what was happening. And we all know that as a picture is worth a thousand words, it takes a very long time and is very difficult to present a good verbal picture of the weather in just a couple of minutes.

All in all, the individual GA pilot was always in a very dark corner when it came to keeping up with weather information in flight. If you are willing to spend the money, that day is now coming to an end. Modern technology now gives the GA pilot the ability to have in the cockpit in real time all the weather information available to a FSS briefer or on an Internet weather briefing service.

The new technology raises a wide range of issues, including system capabilities, available hardware, costs, and user issues, including what these systems can do to help, and how they may cause you problems.

All of the providers currently offering services to the GA public provide two basic sets of products: textual weather reports and radar (generally NEXRAD) images. Additional products are expected as this business develops, but those two are what is generally available today. That said, there are no doubt a lot of expectations among the pilot community about what they will get, and what they can do with what they get. As we shall see, not all these expectations are going to be met.

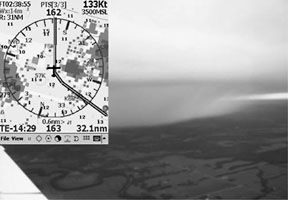

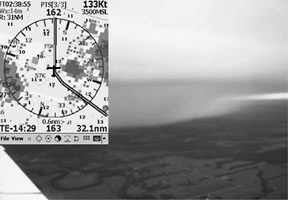

Many pilots are looking forward to the radar image capability as a substitute for heavy, expensive and maintenance-intensive airborne radar units for picking their way between thunderstorm cells. First and foremost, these systems do not provide a suitable replacement for airborne thunderstorm detection equipment, either radar or sferics.

There are time delays inherent in collecting and distributing NEXRAD images, and you are looking at data that are several minutes old. Also, the resolution of the system is not as detailed as airborne radar systems, particularly at short ranges. Bendix/King warns the users of its data link equipment about this in the following words:

[Flight Information Services (FIS)] information is to be used as a strategic planning tool for pilot decisions on avoiding inclement weather areas that are beyond visual range or where poor visibility precludes visual acquisition of inclement weather. FIS information may be used as follows:

To aid the pilot in situational awareness of hazardous meteorological conditions.

As a cue to the pilot to communicate with the ATC controller, AFSS specialist, Operator Dispatch, or Airline Operations Control Center (AOCC) to get further information about the current meteorological conditions.

In no case should the pilot take any evasive action based solely upon the FIS display. The FIS information is intended for assistance in strategic flight planning purposes only and lacks sufficient resolution and updating necessary for tactical maneuvering.

Thus, for the pilot of an aircraft without onboard thunderstorm detection equipment, data-linked weather radar information is not going to provide the means to pick ones way through lines or areas of weather. It will merely provide an idea of the extent of those lines or areas so they can be avoided entirely, and so the pilot can make some good plans in a timely manner.

When It Works

A weather uplink can provide a very important supplement to airborne sensors in two areas. First, it will provide a big picture of the extent of the activity so the pilot can make larger, overall strategic plans on general routing. Second, it will provide the pilot a picture of the weather viewed from other angles.

A major factor in the 1977 Southern 242 accident in which a DC-9 was mistakenly flown directly into the most intense portion of a line of thunderstorms was the pilots misinterpretation of the airborne radar. He thought he was penetrating the thinnest portion of the line on the radar.

One inherent limitation of radar is that it cannot always see the full depth of weather. The attenuation effects of weather on radar energy allow severe weather to hide behind other cells, or for cells to appear much shallower than they really are.

In this case, the pilot saw a line of heavy returns with one area that appeared to be very thin. Believing this to be the thinnest and weakest portion of the line, the pilot went straight into it. What he was actually penetrating was a Level 6 cell – the strongest cell recorded in northern Georgia over many years. It was not until he was already in it that he realized his mistake, and by that time, it was too late.

The intense hail and extremely heavy rain destroyed both engines and even cracked the windshield. In such a case, having a composite picture of the weather viewed from several directions can provide the pilot a much better idea of what hes really looking at – whether its really just a thin line with clear air behind it, or whether hes just looking at the leading edge of a very heavy and deep band of weather.

This will also provide the pilot of an aircraft equipped with appropriate thunderstorm detection equipment an idea of the breadth, depth, and percentage of coverage of areas of activity, thus allowing a well-informed decision on whether to circumnavigate the area completely, or try to pick through it.

Perhaps the area which will be most used is the ability to get current METAR/TAF or other text data such as PIREPS without leaving the ATC frequency or tying up the controllers bandwidth. Instead of waiting until the controller has a chance to dig out the desired information and read it to you, or trying to get through the cacophony on 122.0, you will be able to obtain all the information on your own with no frantic copying down followed by interpretation of your scribbling.

This availability of information provides two main advantages. First, the pilot can request and receive a larger list of data – TAFs as well as METARs, reports on more stations, etc. It also makes it possible to get follow-up on weather data.

For example, if you request weather on your destination and alternate, and both are sour, you can easily get data on a few other places as potential diversion airports. Asking the controller for more stations is often impossible due to his lack of time to deal with non-essential communications, and with FSS, there may be others talking to the briefer before you work out what you need, and then youre back to the end of the line.

To get this capability, first you need to buy the equipment, then you need to subscribe to an information service. The two main pieces of equipment are a data link transceiver and a display unit.

The Hardware

Bendix/Kings entry in this field is a choice of three multifunction displays – the KMD-250/550/850 units – plus the KDR 510 VDL Mode 2 Data Link Receiver. NEXRAD graphics, METARs,TAFs, PIREPs, AIRMETs, SIGMETs, and a host of other weather products are available. Basic text products are free, while graphical products are available through The Bendix/King Wingman Services subscription.

Bendix/King delivers the data through a network of Honeywell ground stations that uplink the information to the airplane. As part of an FAA program called Flight Information Services, Honeywell was granted use of two frequencies to broadcast weather throughout the United States.

Because the signal comes from ground stations, the signal can be blocked by terrain or other obstructions, particularly at lower altitudes. Bendix/King says minimum coverage altitude is 5,000 feet agl, except for regions of precipitous terrain, where coverage may not be possible. You may get reception at lower than 5,000 feet – on the ground, even – if you have a direct line of sight to a ground station.

At altitude, you will generally get reception from 5,000 feet agl to 17,500 feet or more if youre within 70 nm of a ground station. The company says coverage has been observed as high as FL 450.

Coverage is shown at 5,000 and 15,000 MSL in the attached figures. Other providers utilize satellite communications systems, which do not have the same limitations.

How much will all this cost you? Plan on spending at least $10,000 to put the equipment in your airplane and another $50-$100 a month or more to subscribe to the data services. The KMD-250 runs around $5,000, and another $5,000 or so is needed for the KDR-510 data link unit. The higher-end KMD-550 and KMD-850 are about $8,000 and $13,000, respectively.

Another hardware option is the Avidyne FlightMax EX-500 multifunction display. Along with the typical MFD features, this unit includes its own internal satellite data link to receive NEXRAD radar data from a satellite communications network. Installed price of this unit is a bit over $10,000.

Arnavs System 6 MFD-5200 also has data link weather capability when combined with the DR-100 UpLink Receiver. This package also runs in the $10,000 range. And UPSAT is offering a similar service in conjunction with AirCell to provide text and graphical weather (along with a bunch of other functions including e-mail access) on the MX-20 MFD. The DataComm 500 data link unit runs about $2000 in addition to the $8000 or so for the MX-20.

Of course, all of these MFDs include a wide range of other capabilities, including moving maps and overlay of a variety of other information including airborne radar/sferics, route data from GPS nav systems, terrain databases and even digital charts.

In addition, if you have a Garmin 430/530 GPS/nav/comm. (or $10,000 to $15,000 to install one), you can have these data displayed there if you add the GDL 49 data link receiver and subscribe to the EchoFlight service distributed via satellite. This service can also be used by the FlightCheetah system (around $5,000), which is a portable laptop-like device, or your own laptop when combined with a satellite transceiver and their software (around $1,800).

More portability comes from Control Visions Anywhere WX, which uses a satellite phone to download flight information to a yoke-mounted PDA. Anywhere and the PDA can also function as a portable GPS and even a solid-state attitude indicator. Full boat for the package including satellite phone is less than $3,000 to $4,000, depending on whether you want the attitude indicator, but you have a bunch of wires to deal with.

Now What?

Another question is how you are going to learn how this all works. Bendix/King has provided an on-line tutorial for its services, but it is not particularly comprehensive. Avidyne is considering development of a training CD for the FlightMax EX500, but that may be only an emulation program much like the Garmin 430/530 simulator that many pilots have on their computers. Arnav does not advertise any training systems for its MFD-5200. And Howard Reismans Electronic Flight Solutions is not yet offering any programs in this area.

As far as data services, Bendix/King will provide free text weather (METARs/SPECIs, TAFs, and Pireps) to anyone who buys their system, but the NEXRAD coverage is $49 to $59 per month, depending on term of contract. Additional packages not currently available include graphical METARs, Convective Now/Forecast, Icing, Turbulence, Winds Aloft, Translated Text, Animated NEXRAD, and Nationwide (U.S.) Lightning. Prices for these extra services are not yet available.

Services compatible with other systems run $50 to $100 per month. The EchoFlight service runs $25 per month and $0.50 to $1 per view. Satellite phone delivery will incur connection charges at as much as $0.99 per minute in addition to the monthly service rate.

And Now the Downside

While there is no doubt that systems can provide a tremendous improvement in the information available to the pilot in flight for the purpose of making well-informed in-flight decisions, they are not magic. They also raise issues of cockpit management with the addition of any new equipment in the GA cockpit. Advanced avionics such as these can, if the pilot is not properly organized in his use of such systems, actually add to rather than decrease cockpit workload at critical times.

Anyone whos ever surfed the Internet is aware of how easy it is to get zoned-in. Wives, children, car crashes in the street, or even burning buildings (including the one you are in) can fade out of the span of the surfers attention. Everyone who has gone through instrument training knows how fast the airplane wanders away from heading, altitude and airspeed when they divert their attention to, say, finding an intersection on an en route chart.

The airlines always give the pilot not flying the task of talking to company dispatch and reviewing weather options. In single-pilot GA operations, the pilot will not have this luxury.

To a great extent, the infusion of technology into the cockpit is rapidly making the two-axis autopilot more of a necessity than a nice-to-have item. Technology is continuing to increase both the rate at which information flows into the cockpit, and the density of that information.

Pilots whose attention is absorbed in obtaining, interpreting and implementing this info will get busy interpreting the weather, selecting new routes on the en route chart, getting new clearances and programming them in the GPS. They wont be paying as close attention to flying the airplane as they might have in the past.

Pilots attempting to go through the procedures necessary to call up weather information – and then to read, interpret and act – are going to have to let George take on the task of keeping the airplane upright and on course while they do so.

This problem would be exacerbated in the case of a pilot using a laptop computer or other portable device laying on the right seat rather than a panel-mounted device. There are several issues here.

First, the device is going to be well out of the pilots normal field of vision. That means he will have to turn his head and look down to view the device, creating problems of both vertigo and placing the flight instruments outside the field of view.

Also, unlike panel-mount units, laptops are not designed to be operated with one hand. This creates an awkward situation either by attempting to work the unit with the right hand only, or by twisting around to bring both hands to bear.

Another problem is that the laptop is now a missile hazard in event of either turbulence or ground impact. Perhaps my fighter background strengthened this concern, but I have always been apprehensive about anything loose in the plane, a position strengthened when, in turbulence, I was nearly hit in the back of the head by a Labrador retriever.

There are also usually wires running around between the cigar lighter, the laptop, the satellite receiver, and the stick-on antenna, which get in the way for both normal and emergency operations. While the FARs do not address such issues as regards equipment that is not installed, this may be a case where what is legal is not necessarily safe.

I suppose that there will be various attempts to secure these portable devices. For example, Ive seen a lot of both commercially produced and homemade brackets for hand-held GPS receivers. In most cases, I find that bracket-mounted units are either blocking important panel-mounted instruments or not in a good position for viewing.

This includes being placed too far to the side or down, or being much too close to the viewer to enable good eye focus. In other cases, the unit is mounted on the glare shield, blocking some of the pilots all-important view of the outside world.

Finally, and perhaps most important, is that the technology is new enough that early adopters report the system doesnt always work as advertised. Notable among the complaints are extremely long download times for the weather graphics and outdated images.

Some users even complain that, by the time the NEXRAD image loads, theyre past the weather in question.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that the implementation of new devices to bring real-time weather data into the cockpit of GA aircraft will provide major improvements in aviation safety. Pilots will be provided with information in a manner that is both useful and timely.

However, as with every other new technology introduced into the cockpit, the opportunity for misuse and abuse is also created. The fact that none of this equipment is directly addressed in FAA-approved training programs, pilot certification regulations or practical test standards leaves cause for many concerns.

The price for entry, as well as to stay in the game, is rather steep for the owner of a light single, but probably well within the range of cost of doing business for the high-performance retractable or twin operator. But all in all, this new technology provides the opportunity to expand the pilots view of the weather far beyond past limits, and that cannot help but be good.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Hits and Misses.”

-Ron Levy is an ATP, CFII and director of the Aviation Sciences Program at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore.