By Orin Koukol

Mountain waves were blamed in 10 fatal airplane accidents in the continental U.S. from 1996 to 2006. Not by coincidence, three of them occurred within four miles of Eagle Peak in the Warner Mountains of Northern California. This account of those three accidents suggests ways to avoid mountain waves and to escape if you do encounter one. It is also a lesson that one doesnt have to fly close to the larger mountains to encounter a mountain wave-smaller ones will do quite nicely.

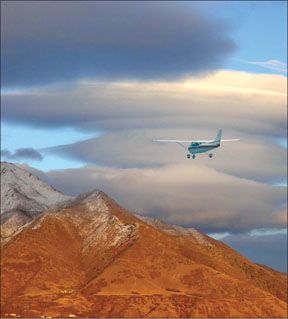

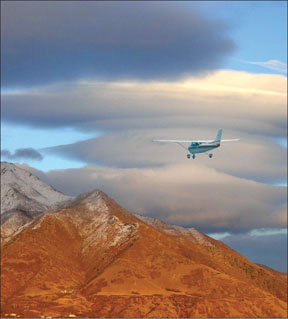

In fact, by western standards, the Warner Range is small. Oriented north and south, its basically a single ridge 60 miles long. Eagle Peak is less than 5000 feet above the valley floor. But its western foothills rise gradually and its eastern face plunges steeply. When the weather gods combine a layer of stable air and strong west winds over the range, strong mountain waves develop east of the crest.

Victor 165 connects the Mustang VOR, near Reno, Nev., and the Lakeview, Ore., VOR some 182 miles distant. The airway parallels the crest of the Warners for nearly 30 miles. By its presence, it lures pilots into an area where deadly mountain waves generated by the Warners can bring down the unwary. The three accident airplanes well discuss were on V-165 when they dropped from radar.

Beech Baron, Jan. 1996

The Beech Model 55 Baron departed Everett, Wash., at 1943 local time on an IFR flight plan for a night flight to the North Las Vegas (Nev.) Airport. The 35-year-old Instrument-rated Private pilot climbed to 14,500 feet to cruise VFR-on-top. For two hours, the flight was routine as the Baron crossed Washington, Oregon, and into Northern California. Scattered clouds were far below, at 7300 feet; the visibility was 10 miles.

Three miles from Eagle Peak, the pilot reported a sharp drop in the outside air temperature. Two minutes later, radar contact was lost as the Baron descended, without clearance, through 12,300 feet. The pilot did not respond to radio calls. The Baron had dived, almost vertically, into the mud of a drying lake. Although the engines and propellers were 20 feet below the surface, they were recovered. Both engines were developing power at impact and the aircraft had not broken up in flight.

The NTSB later determined that the wind at 12,000 feet was blowing from 290 degrees at 40 knots with an OAT of -14 degrees Celsius. From the reported drop in air temperature, the NTSB concluded that the Baron was at the western edge of a lee wave cloud, or lenticular, just before dropping from radar. The cloud was four miles east of the ridgeline. The Safety Board said that the pilot encountered a mountain wave condition.

Twin Commander, Nov. 2001

The Twin Commander AC500S carried specialized avionics for fire-fighting, including two Garmin 430s. The 57-year-old pilot owned this Commander and several others. He held Airline Transport pilot and Flight Instructor-Instrument certificates with ratings for airplanes and gliders; he had accumulated more than 20,000 hours.

Forty-five minutes before departure, the pilot filed an IFR flight plan.He requested, and received, only the forecast winds aloft. The area forecast and Airmets the pilot did not receive called for overcast ceilings at 8000 feet with tops at 25,000 and warned of mountain obscuration, moderate turbulence and mountain wave activity.

When the Twin Commander took off at 1037 local time, Reno was reporting an overcast ceiling at 5000 feet, 10 miles visibility, and a surface wind of nine knots. Alturas, west of the Warner Mountains and 24 miles northwest of Eagle Peak, was overcast at 3400 feet with 10 miles visibility. The pilot departed under VFR, took his IFR clearance in the air, but then cancelled IFR before reaching the MEA of 14,000 feet.

Oakland Center continued to record the Twin Commanders radar returns on V-165 at 10,500 feet until the target was about 500 yards east of Eagle Peak and descending. The wreckage was found 1200 yards northwest. The Commander was upright, with the cabin crumpled vertically under the wings, 200 feet below the ridgeline.

The NTSB determined that the wind at 10,000 feet was from 245 degrees at 45 knots and -1 degree Celsius. Clouds were layered from 9000 feet to 30,000 feet. The air was stable from 9000 to 19,000 feet. The NTSB concluded the Twin Commander encountered a mountain wave with downdrafts exceeding 3500 fpm, turbulence and icing. It faulted the pilot for not obtaining a full weather briefing from an FAA-approved source.

Cessna Skylane, April 2003

The turbocharged Skylane RG departed Scottsdale, Ariz., with two aboard at 1214 local time, bound for Lakeview, Ore. Before takeoff, the 46-year-old Instrument-rated Private pilot obtained an overview briefing from a Flight Service briefer after saying that he had been on DUATS earlier. The National Weather Service had not issued Airmets or Sigmets for severe icing, severe turbulence, or mountain wave conditions.

Twenty-seven minutes after departing VFR, the pilot asked for an IFR clearance. During the next five hours, he changed altitude several times, apparently seeking a smoother ride. Approaching the Warners, he descended to 14,000 feet.

Near Eagle Peak, the pilot said that he was about to go into the soup and asked for Pireps on icing. The controller replied, No reports in your area. Five minutes later, the Skylane began an uncleared descent that reached 3000 fpm. During the descent, the Skylane changed course to the right, toward lower terrain. At about 1715 local time, a witness heard an aircraft engine, followed by the sound of an impact, but couldnt see the airplane because of blowing sleet. The last radar return was from 3.3 miles southeast of Eagle Peak. The wreckage was two miles north.

The NTSB determined that the wind at 14,000 feet was 57 knots from 230 degrees with a temperature of -17 degrees Celsius. The modeling program indicated cloud bases at 9200 feet, tops at 13,000 feet and mountain wave activity with downdrafts exceeding 5000 fpm.

The NTSB concluded that the Skylane accident was caused by an encounter with mountain wave activity with downdrafts and severe turbulence.

Lessons

The Baron and Skylane accidents are surprisingly similar. The Baron pilot was operating VFR in very dark conditions when an NTSB meteorologist placed him at the edge of a lee wave cloud. He probably did not see the cloud until he was in it.

Once in the cloud, the airframe and windscreen probably iced rapidly and forced a descent into even worse turbulence and downdrafts. The location of the wreckage suggests that the pilot attempted to retreat with a 180-degree turn. An ice-induced stall may have preceded the Barons contact with the lakebed.

Minutes before descending, the Skylane pilot told the controller he was about to go in the soup…. There, he probably encountered icing and downdrafts. Once iced, the Skylane would descend into the turbulence and downdrafts below.

In the Twin Commander accident, it appears a highly experienced pilot simply flew into a strong mountain wave. The last radar return and the wreckage location suggest that the pilot flew parallel to the ridge, about 500 yards east, for more than a mile. Its difficult to imagine a worse place to be when winds are strong.

The diminutive size of the Warner Mountains may be misleading. The unfortunate placement of V-165 probably contributes also to the high accident rate. When mountain waves exist, V-165 routes air traffic dangerously close, or even into, the wave activity.

The downdrafts of strong mountain waves equals those of Category 5 thunderstorms-the NTSB said that the Commander faced downdrafts of 3600 fpm; the Skylane encountered 5300 fpm. If youre high and have enough power, you can escape by turning into the wind. A second Commander pilot did that and survived (see the “Always Turn Away From Terrain” sidebar), but thats not for everyone. His airplane was turbocharged. He was losing only a couple of hundred feet a minute and he knew that rising air was only a few miles away. He elected to trade some of his 4000 feet of cushion for the rising air he knew was across the ridge. But not everyone is so lucky.

Also With This Article

“Always Turn Away From Terrain”

“Another Twin Commander”

“Planning For The Mountains”

-Orin Koukol owned a Part 135 operation for 26 years. He has ATP and CFII tickets, and a little over 12,000 hours.