by Paul Bertorelli

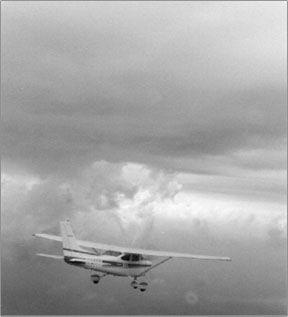

Flying convective weather is sometimes like feeling your way around a dark closet. And theres more than one way to find the doorknob.

For all the modern tools available for ducking thunderstorms-sferics, airborne and ground radar, datalink weather-in the end, it all comes down to looking out the window and flying where its least scary. Or perhaps not flying at all. Even with onboard radar and sferics, theres an understandable reluctance to poke your nose into a nasty black cloud that a Stormscope says is benign. When the eyeballs and the instruments dont agree, the eyeballs usually win.

And not all eyeballs see the same thing, either out the window or from the divined sputterings of a Stormscope. One mans golden path home is anothers cathode-ray sucker hole. In thunderstorm avoidance, both can be equally right or wrong.

But before any of that can happen, theres an overarching strategic question to answer: Is this mess flyable at all? When some nasty black line from hell comes sweeping across the plains rolling over trailers like dominoes and spewing the hail the size of canned hams, is flying simply out of the question? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. In reality, its probably more often yes than no if you analyze all of the information available these days.

That turns out to be a lot, much of it Internet-based. Forgetting the finer points of tactical avoidance for a moment, you need at least three things to make the go/no-go decision on a convective day: All the ground radar information you can find, a solid-gold chicken-out plan and enough nerve to carry out your decision either way. (The Catch-22 here is that nerve comes from experience but you cant get the experience without having the nerve.)

A Long Trip

Every pilot looks at the convective decision process a little differently, depending on experience and outlook. I was reminded of this on a long trip from Florida to Oklahoma last winter into the teeth of a blistering westerly. An advancing cold front had kicked up a fierce line on a northeast/southwest alignment from southern Illinois to extreme southeast Texas. The tops of this thing were near low earth orbit and it looked solid. (It wasnt.)

We were to fly my friends Bonanza westbound and when he met me at Galaxy Aviation in Orlando, I was intently eyeballing the radar loop from a Louisiana NEXRAD site. By the time we got there the weather would be somewhere else-further east-but I was curious about the extent and depth of the line. And heres where the divergent judgment played out.

We going? my friend asked, with the most casual, diffident glance at the radar loop. It was a loaded question. I knew he was in go-mode, having decided that the system was flyable and, if it wasnt, hed deal with it tactically 600 miles west of my nerdy little radar lab. His question was a push-to-test: Did I see anything he missed and was I willing to launch for a four-hour look-see? I could see he was open for a convincing counterview but somewhat doubtful Id produce one.

On the other hand, I was in strategic-wait-a-minute mode. Would the line to be too big a chunk to bite off when we got there and would we be better off delaying overnight in the comforts of Orlando rather than getting chased across Louisiana by tornadoes? His perspective: more time dodging plains thunderstorms than I have in pants. My perspective: I dont mind a little hail and lightning risk, but if were going to duck into a bolt hole, maybe do it here rather than some Godforsaken Mississippi Muni.

One last look at the radar: that line had tiny crevices in it, the kind that dont look like much until you drive right up to them and see blue sky. I could see little fingers of dry air ripping into the rain, working from south to north. Strategically, this was clearly promising. It met my look-see test; I could always chicken out later.

Tactical Tools

Although thunderstorm avoidance gear for light GA airplanes is undergoing a quantum leap in capability, we had what many pilots do: a Stormscope, specifically a WX-10. I dont like the early Stormscopes much; theyre susceptible to radial spread and I find the ranging suspect, so Im reluctant to put much faith in them for any but the crudest decisions. I have more experience with the later Stormscopes and the Strikefinder and trust them more, but not completely.

My perspective: WX-10s are random dot generators. My friends perspective: many hundreds of hours with this very instrument in this airplane-a Bonanza-and demonstrated faith in its azimuth accuracy.

Fast forward four hours. We encountered the wispy edges of the line right where my radar study said it should be: west of the Mississippi/Louisiana state line. An earlier check with Flight Watch revealed that the line was wider to the north of us, narrower to the south. At its widest, it was easily 150 miles wide and dense with cells. The sky looked forbiddingly dark to the north, lighter to the south. Yet, the damn WX-10 showed a clearer dot pattern to the north.

If we went that way, we would save at least 200 miles, perhaps more, on a direct route to the destination. Deviating south would put us well into Texas, then we would be into a strong headwind on the west side of the front. More miles, more time, but maybe fewer bumps.

We hemmed. We hawed. We flipped and flopped. My friend thought the Stormscope showed the way to salvation; I thought it had the avionics equivalent of small pox. We asked the Center controller for a neutral opinion: Looks pretty bad both ways.

A new hybrid perspective emerged: following the most conservative judgment is rarely wrong. Instead of jungle rules, call it wimp rules. We headed for Texas, around the south side of the line, conceding that wed add a lot of flying distance to the trip.

High or Low?

When navigating thunderstorm lines-I hesitate to use the word penetrate-altitude matters. It matters a lot. For pressurized airplanes capable of the teens and higher and using airborne radar, in-cloud penetrations during the summer will be at or near the freezing level, which invites icing and increases the likelihood of lightning strikes. These may be acceptable risks but they are, nonetheless, real.

For lower flying aircraft-we were turbocharged but not pressurized-higher is usually better but not necessarily the teens or 20s. Higher keeps you clear of the haze level and above enough of the tops to pick an obstacle-free path through the lower clouds surrounding the typical thunderstorm.

Summer or winter, these tops seem to be around 10,000 feet or there are layers around that altitude. During the summer, higher is usually smoother, since its above the altitude where water vapor condenses to form non-convective clouds.

When bumbling along semi-blind with only sferics and eyeballs, the most conservative approach-other than no flying at all-is to remain clear of cloud whenever possible, using the sferics to pick the best path, if needed. If you can see where youre going, theres not much discomfort in skirting even a nasty looking cell in the clear.

Again, theres some hazard in that, however. Turbulence or heavy rain might no be issues clear of clouds but hail shafts get outside of cloud now and again. So do lightning strikes. Some rules of thumb call for giving cells a 10 to 20-mile berth but sometimes thats not remotely practical. In cutting it closer, you have to make your own judgment based on conditions you see outside the window, on a Stormscope or on radar.

If cloud penetration is unavoidable, I do it only with a Stormscope well clear of dots through at least 40 degrees to either side of course. And Id much prefer one side of the course clear of dots so theres an escape hatch if the penetration looks bad, even if it requires some miles of flying to find such a wide slot.

My friends perspective is more sporting. Hell penetrate a cloud or rain area mostly on a favorable Stormscope indication and reason able distance from the strike indica tions. But reasonable is a fine-point judgment call he can make with the WX-10. Not having the same faith in that model, I give the dots a much wider berth and Im not willing to go between defined areas of dots unless I can stay out of clouds. And in the best of conditions, a WX-10 doesnt define areas that well.

And at this juncture, we confronted our next divergent judgment. We were at 14,000 feet into a stiff headwind of 50 knots. Descending to 8000 feet, we would clearly pick up 10 to 15 knots of groundspeed, but we would be almost entirely in cloud and relying entirely on the WX-10 for what turned out to be a 100-mile wide line with flyable gaps in it.

We debated this for several minutes, diddled the GPS to see what the additional speed would do for our plans to fly the trip non-stop, then compromised. We descended to 12,000 feet, still in the clear and above most of the tops.

The actual penetration of the line was a non-event. We ran through some bumpy cloud cover, in and out patches of heavy rain and in and out of icing as we neared the colder side of the front. We picked a path with a combination of Stormscope and eyeballs, mainly steering toward the bright areas and away from what looked nasty, just as youd do with no Stormscope at all. After 30 minutes of that and on a heading that was essentially a 400-mile DME arc from the destination, a long narrow slot appeared and we finally turned toward home, cruising through a shower into the smooth, clear air behind the front. As the sun set, we were above a pan flat undercast of the type thats common in the plains during the winter.

After a long quiet spell of staring at the sunset, my friend idly wondered how you teach someone-say a new Cirrus owner with 300 hours-how to do what we had just done in order to get maximum utility out of an expensive airplane.

Neither of us had an easy answer. A pilot simply has to gather all of the available information for the strategic decision to go or stay and then work the tactics on the fly. You cant learn it from the comfort of an armchair.

Adding It Up

All of this jinking and dodging added up, of course. Id guess we flew an additional 300 miles-a couple of hours-to find our way through that front comfortably. The deviations nixed any chance of making the trip non-stop; we refueled in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Rewinding back to my strategic deliberations in Orlando, was all that stooging around the cells worth it? Yes, but just. At some point, its got to be better to cave in and wait a day or a few hours, not because of the hazards involved but because of the sheer effort of grinding around trying to find holes youre sure are there somewhere is exhausting.

And again we come to the dual perspective: my friend is bone-in-the-teeth determined, does a trip like this once a month and thinks nothing of flying for eight hours straight. He uses the Bonanza like a DC-9 and couldnt see how that front was a showstopper, even it if meant a couple of extra hours of flying. He knows exactly when to quit.

On the other hand, Ive never seen a Lazy Boy recliner I didnt at least want to flight test for an hour or two, preferably with a good book. In weather flying, Im hardly Chicken Little, but given the chance, I like to avoid hard work and panic on the same day.

Nonetheless, our trip proved that dual perspectives can work as one and two guys can find their way out of a darkened closet. Even with a WX-10.

Also With This Article

“Flyable? Yes; Heres Why”

“A Convective Decision Checklist”

“Is NEXRAD Good Enough?”