When blessed with a choice of approach procedures at their destination, instrument pilots usually will choose the one providing the lowest minimums, in the belief doing so affords them the best chance to get in. That may be true when the weather is at or below minimums for the airport’s other procedures, but it’s not the only consideration.

What if you miss? The reason for going missed may not involve your skills: The preceding flight may close the runway, for example. Perhaps transitioning from en route airspace to the ILS puts you in convective weather or requires a lengthy vector? Is the procedure with the lowest MDA or DH really the best choice?

The Miss

My favorite example occurred on a late fall evening in the Raleigh-Durham, N.C., area many years ago. I was trying to get a 172 into the Horace Williams Airport (IGX) at Chapel Hill, N.C., At the time, the facility lacked any published approaches, relying on only an ASR (Radar) procedure. I had a choice according to ATC: approach from either the east or the west. Both offered the same MDA. The weather was bad enough there was a real possibility I would go missed.

Since I needed to drop a passenger before continuing north, the best option for an alternate was the nearby Raleigh-Durham International Airport (RDU), located east of Chapel Hill. I was arriving from the east and opted to let ATC vector me to the west of IGX and fly the ASR with an easterly heading. That way, I would be pointed at RDU if couldn’t get into IGX. Sure enough, there was nothing to be seen when ATC advised I was over the airport, so I added full power and climbed out for vectors to an ILS at RDU, for which the 172’s panel had already been set up. The result would have been the same when approaching IGX from the east, but I eliminated a 180-degree heading change from the busiest portion of the flight.

288

Missed approaches also can lead us places we may not want to go. An obvious example would be into nearby convective weather, or toward steeply rising terrain. Why do either if there’s another option, like approaching from over the higher terrain and circling to land if the weather allows?

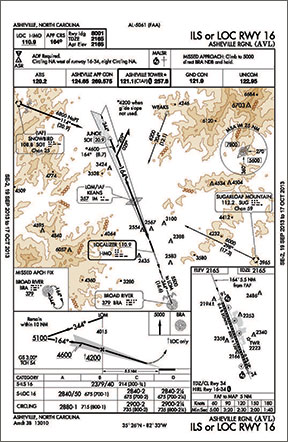

Available equipment also may help make the decision for us. Referring to the ILS/LOC RWY 16 procedure at Asheville, N.C. (AVL), pictured at right, note the miss takes us straight out on a climb to hold at the BRA NDB. The problem? There are still a lot of aircraft in everyday use without an IFR-certified GPS navigator. They may have an ADF, but when was the last time it was used or checked? Or, what if BRA is Notam’d out of service? A portable GPS/tablet probably is more accurate and useful than the cranky old ADF in the panel, but it’s not legal for IFR use. The solution? Either choose a different procedure or negotiate the terms of a miss with ATC before being cleared for the approach.

Circling

Approaching AVL at night also presents another planning challenge. The procedure clearly states circling is not authorized at night, or to the west in daytime. That’s due to the steep terrain nearby and, especially, a ridge to the west of the runway. If you’re arriving AVL from the north at night with light northerly winds on the surface, making a straight-in to that 8000-foot runway and planning to land downwind shouldn’t be much of an issue, depending. Getting a vector for one of AVL’s straight-in approaches to Runway 34 might be the better option, however.

Of course, circling brings with it its own challenges: Low-level maneuvering in poor weather, perhaps at an unfamiliar airport, perhaps at night. It’s been a very long time since passenger-carrying scheduled carriers operating under Part 121 were allowed to conduct circling approaches, and many other commercial operators avoid them, too. That doesn’t mean the rest of GA should, however. In fact, sometimes a circling approach—however technical the circling may be—is the only way to get in. The sidebar above highlights one location, Aspen, Colo., where circling approaches are the only game in town.

Meanwhile, if we want to avoid circling at all costs, we may need to flip through all of the procedures available at our destination. Some may not allow us to get under the weather, some may require a downwind landing, some may not be allowed at night and some may not be compatible with our equipment.

Equipped

About that equipment…Do you have everything aboard the aircraft necessary to safely and legally shoot the approach? Is it in good working order, with a current database? You’ve done the required 30-day VOR check, right?

A few weeks after getting some panel work done years ago, I found myself shooting an ILS to a very familiar non-towered airport. It perhaps was the first time I had executed the ILS to that facility, however. It also was the first time I had shot a for-real ILS with my spanking-new Garmin GNS530. As part of the avionics shop’s work, it had removed a functioning KR-85 ADF, since I was taking advantage of the FAA’s then-recent rule change allowing an IFR-certified GPS to be used in lieu of an ADF. Thanks to my misconfiguring the new audio panel, I failed to identify the outer marker and didn’t follow the glideslope needle. A miss was called, and I got my act together well enough to get in on the next attempt. There are several punchlines from this experience.

Even though my panel was almost state-of-the-art for the time, I wasn’t very experienced in using it. Some new gadgets, along with new rules, plus my old-school expectation to hear the marker beacon announce it was time to begin the descent conspired to leave me well above the glideslope. The miss was a no-brainer, especially since I knew exactly what had happened and how to fix it.

Being familiar but not proficient with the equipment, I may have been better off using the #2 nav/com, a KX-155 hooked to a second ILS indicator, to shoot that approach and followed along on the Garmin’s moving map. The primary mistakes I made were depending on the marker beacon annunciator to decide when to join the glideslope, plus forgetting to mash the correct button on the audio panel. Given all that was going on, I might have been better off selecting a VOR approach to the same runway. Your mileage may vary.

Weather

Weather’s impact on which approach we choose is rather obvious: If the minimums aren’t low enough, we’re not getting in. But weather also should affect our choice in other ways. For example, what if there’s a storm cell hovering along the final approach path? Should you plunge into it anyway, knowing there will be a runway when you break out on the other side? Of course not.

Just as with terrain and equipment considerations, planning ahead for the miss, even if you don’t need it, can pay off big dividends if that storm cell is sitting on the other end of the approach, over the missed approach. Storm cells also can help us choose a different approach if, for example, they’re sitting on top of the direct route we would take to execute one approach, but far enough away from another procedure to make it a no-brainer. Of course, convective weather is perhaps the most violent with which we have to contend, but it’s not the most dangerous. Icing comes to mind.

If you know you’ll be picking up ice on the descent for your destination, the chances are pretty good you’ll pick up more of it if you miss and have to climb back into the freezing clag. In most personal airplanes, that’s some bad juju, something we should try to avoid. There are three basic ways to do so.

The first and most obvious is to divert. While still above the icing conditions, go to a facility either lacking icing or with missed approach procedures featuring altitudes which won’t force you to pick up more of the stuff. Yes, it may take a few minutes of planning to figure out the best option, but that’s one of the things straight-and-level, and autopilots, are for.

Another option is to pick an approach you would be hard-pressed to miss. Instead of shooting an RNAV (GPS) procedure to your preferred runway when the weather’s at its minimums, choose the ILS to an intersecting runway or land downwind. We wouldn’t suggest circling with ice on the wings, however. The third option is to choose an approach where the miss won’t put you back in icing, if possible.

There are many weather-related reasons to choose one approach over another, but the final one I’ll mention involves intimate knowledge of how certain conditions may affect the destination. An airport located next to a large body of water, for example, will experience fog when the air temperature and dewpoint are close together and there’s an offshore breeze. Approaching from over the water could require very low minimums, while approaching from land might be done on a visual. Either way, approaching from land and missing will put you in the clag, although it may not be very high.

Terrain

Which gives us a good segue into discussing terrain as a factor to consider in choosing an approach. We’ve already looked at airports like Asheville and Aspen, where terrain presents certain challenges or forecloses certain actions that would be normal at other destinations. As referenced a moment ago, airports in coastal areas or near large bodies of water often can be impacted by low weather. The flipside is that airports not that far inland can be in the clear.

My current location, near the Gulf of Mexico in Florida, infrequently sees below-minimums weather at nearby Sarasota-Bradenton International (SRQ). When SRQ is down the tubes, it’s usually due to either widespread convective activity with low ceilings or fog forming near the Gulf and moving over the airport. The opposite is true, also: Low-lying fog frequently forms just a few miles inland, but SRQ will be and remain wide open. While the area around SRQ is as flat as it gets, mountains aren’t the only kind of terrain to consider when choosing an approach.

My double-I was very fond of reminding me: “Now, while you’re straight and level, is a good time to get set up for the approach.” While that was back in the days well before GPS, his advice still rings true today. Choosing the best procedure is the first step.