We all saw the recent image of a Mooney 201 suspended 100 feet above the ground and tangled in an electrical transmission tower on a dark and gloomy night. Without knowing the details, we all probably asked ourselves, “How did that happen?” The NTSB’s preliminary report on this accident is out, and tells us that, as with almost any accident, there was a long chain of events leading up to the Mooney becoming ensnared in the power lines.

We’ve included some excerpts from the preliminary report in the sidebar on page 10. You can read the full document by searching for the report identifier ERA23LA071 on the safety board’s web site, www.ntsb.gov. Bear in mind that this report is subject to correction and addition of new details as the NTSB investigation unfolds and a probable cause is determined. Still, it prompts us to ask: Was the pilot ready for this? Flying personal airplanes sometimes requires us to expect the worst outcome, and we should be prepared for anything. And as we plan and fly trips ourselves, are we ready for all the events that can happen?

DECISION POINTS

Rescuing the 65-year-old pilot and his 66-year-old passenger from their precarious perch took over five hours. Both reportedly suffered “serious” head injuries at the time of the crash, as well as hypothermia from the time they were suspended aloft in the unheated aircraft. First responders had to shut off a major electrical distribution line for the rescue, cutting off power to over 120,000 customers for several hours that Sunday evening of Thanksgiving weekend and prompting one school district to close the next day.

The aviation internet was in a frenzy in the days after this crash, with posters castigating the pilot and assuring anyone that they would never do such a thing. There’s certainly a lot to be learned from this accident, at least what we know now. In the spirit of that learning, let’s look at what we know about this flight so far.

For example, think about the injuries the pilot and passenger suffered. To help keep the same thing from happening to you, before beginning a flight ask yourself, “Am I ready to avoid head injuries by wearing a shoulder harness at all times in the airplane?” Not all airplanes are equipped with shoulder harnesses, although the FAA has made it as easy as possible—paperwork-wise—to install and approve them. If the airplane is not equipped with shoulder harnesses and I have authority to do so, am I ready to protect myself and my passengers by arranging to have shoulder harnesses installed in the airplane today? So-called “portable” shoulder harnesses are available if no approved installations exist, but it’s relatively uncommon for approved harness installations to not be available for a specific aircraft type.

Meanwhile, am I ready to be trapped without heat (or air conditioning) for several hours, by wearing clothing appropriate to conditions or making sure I have blankets, water and other necessities within reach while strapped to the pilot’s seat? And of course, the big enchilada: Am I ready to cancel or otherwise modify the planned flight(s) in the face of a mechanical issue, unforecast poor weather or other events making the flight riskier than I expect?

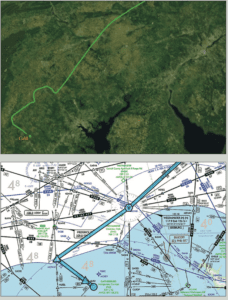

A pilot who lives in the Gaithersburg area provided a plausible explanation for the accident pilot’s 100-degree off-course turn when first cleared to the RNAV (GPS) 14 initial approach fix (IAF), BEGKA. That jog to the northwest is shown in the flight’s actual track in the first image at right, courtesy FlightAware.com. The second image shows the filed route, including BEGKA and the final approach course.

As it happens, there is an almost identically named waypoint, BECKA, only 43 nm northwest of BEGKA. The FlightAware track shows the Mooney turned directly toward BECKA (the wrong waypoint) after acknowledging the clearance. When ATC questioned the airplane’s heading, it’s very likely the pilot was confused and disoriented—his GPS had “the” waypoint dialed in and the moving map showed the aircraft was headed directly toward it.

Knowing you are headed in the “right” direction, but with a controller insisting otherwise, would undermine any pilot’s situational awareness and confidence and set up that pilot for other errors until faith in that awareness is restored. In an already stressful situation—trying to get home in low instrument conditions at the end of a holiday weekend, perhaps needing to go to work the next day—it may be hard to rebuild that awareness in time for the approach. To avoid loss of situational awareness and confidence, and before getting into a situation like this, ask yourself:

• Am I ready to be directed onto the approach, by having reviewed the name of the intermediate, initial and final approach fixes, so that if the controller suddenly clears me direct to one of them, I at least recognize the location is part of the procedure?

• Am I ready to accept a new clearance, by knowing the approximate heading to the next waypoint before turning toward it?

• If ATC throws you a curveball, like a vector to a distant fix that doesn’t seem to make sense, are you prepared to assert yourself and query the controller to get confirmation?

HOMEWARD BOUND

The pair flew the Mooney to White Plains, N.Y., that Sunday morning after Thanksgiving and took off toward home plate, the Montgomery County Airpark (KGAI) in Gaithersburg, Md., to arrive about 5:30 local time that evening, after dark that time of year. Weather at KGAI was IFR with a convective Sigmet in effect; by the time the airplane neared the destination, conditions included low IFR and were below minimums—200 overcast, 1¼ miles of visibility for the airport’s available approach procedures.

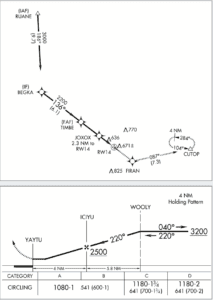

The controller initially offered the RNAV (GPS) A approach at KGAI, presumably to give the pilot something approximating a straight-in arrival but also perhaps to keep it further away from traffic using nearby Washington Dulles International Airport (KIAD). Minimums for KGAI’s RNAV (GPS) A circling approach require a 600-foot ceiling. Remember that ATC’s primary role is separation from other IFR and participating VFR traffic, and controllers are not required to assign an approach they think will result in landing, or even to advise pilots if conditions are below approach minimums. Still, the pilot declined the “A” approach, either recognizing its higher minimums compared to the weather or wanting a straight-in approach to the runway in dark IMC, or both.

The pilot requested and was cleared for the RNAV (GPS) 14 procedure. The clearance direct to the “14” approach’s intermediate fix (IF) appears to have set up a loss of position and situational awareness (See the sidebar on page 9 and the one above). Conditions were still worse than that approach’s required 300-foot ceiling. Still, Part 91 operators have the authority to attempt an approach even if reported conditions strongly suggest it will not result in breaking out at or above minimums.

The Montgomery County Airpark (KGAI) is served by two RNAV (GPS) approach procedures: The RNAV (GPS) A and the RNAV (GPS) Rwy 14. At right are two excerpts from these procedures: The top one is the plan view for the straight-in procedure to Runway 14, which offers LPV service with a decision altitude of 269 feet agl, and weather minima of 300 feet and one mile. The bottom excerpt is from the “A” approach, which by its nature requires a circling maneuver, this time with a minimum descent altitude of 541 feet agl but also comes with higher minima, 600 feet and one mile.

The AWOS was advertising a 200-foot ceiling with visibility of ¼ mile, well below minimums. As noted in the sidebar on the opposite page, the pilot of a preceding aircraft determined visibility was below minimums and diverted to another airport.

Although the “A” procedure would have resulted in less vectoring or flying time, it’s not likely the attempt would have been successful, given the automated weather observation. Opting for the straight-in procedure to Runway 14 was a sound decision, and well worth a try, but it wasn’t likely to succeed; the weather was simply too low.

In the event, the Mooney pilot was below the published crossing altitudes from the start of the procedure, perhaps hoping to get under the ceiling and motoring on to a safe landing. Instead, it collided with power lines before reaching the airport.

QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF

At this point in the flight, you may want to ask yourself: Am I ready to decline an approach if conditions do not fit that approach’s minimums, or if you prefer another procedure (a straight-in vs. circling approach, for example).

Also, am I ready to divert to a different airport before even beginning an approach when reported weather shows there’s no real chance of making it to a landing? A corollary: Am I ready to call off the flight before it begins if conditions make arriving at my planned destination “iffy”? In other words, am I ready to delay, divert or cancel if a successful arrival is seriously in doubt, even if there’s still a chance I might make it in?

INBOUND

An attempted approach with weather below minimums is perfectly safe. But that assumes the pilot flies the procedure as charted. From preliminary reports including ATC recordings and the pilot’s own admission, that’s not what happened.

The pilot turned inbound on the approach and began descending well below the charted altitudes. The airplane crossed BEGKA about 225 feet low. It was 700 feet low at the initial approach fix, and 530 feet low at JOXOX, 2.3 nm from the missed approach point (MAP). The airplane was 64 feet below the published field elevation when it impacted the power line tower well left of the runway centerline and final approach course. The controller issued a low-altitude alert to the pilot shortly before impact, but that was after releasing the pilot to the non-towered airport’s advisory frequency, so it’s unknown if the pilot heard the warning.

The communication recordings reveal the last altimeter setting provided by ATC was 29.44, and the NTSB preliminary report states the altimeter was found to be set at 29.40. “High to low, look out below,” we were taught a long time ago. Four-one hundredths of an inch of mercury results in a 40-foot error in indicated altitude, however, not enough to account for the discrepancy. Instead, the pilot’s comments to 911 suggest he made some ground contact and then was either distracted from or intentionally deviated from approach guidance, drifting further down and to the left before hitting the tower.

On November 27, 2022, at 1729 Eastern time, the airplane was substantially damaged in an accident near Gaithersburg, Maryland. The pilot and passenger were seriously injured. The accident occurred on the return flight to KGAI while the airplane was operating on an IFR flight plan. Dark night instrument conditions prevailed. Automated weather observations included variable wind at four knots, an overcast ceiling at 200 feet and 1.25 sm of visibility in fog. A convective Sigmet was valid for the accident time and location.

After ATC cleared the pilot direct to BEGKA, the airplane turned right, perhaps toward a fix with a similar-sounding name. After ATC repeatedly requested the pilot to turn to a different heading, the controller requested the pilot confirm he had the BEGKA waypoint and spelled it for him. The pilot responded that he had entered the information incorrectly and was making the correction. About that time, another airplane on approach to KGAI announced that visibility was below minimums and requested to divert to another airport.

The minimum altitude at BEGKA, 11.3 nm from Runway 14, is 3000 feet msl. The airplane crossed BEGKA at about 2775 feet continued descending. The minimum altitude at the final approach fix, TIMBE (5.2 nm from the runway), is 2200 feet msl; the airplane crossed TIMBE at 1500 feet. The minimum altitude at JOXOX, about 2.3 nm from the runway, is 1280 feet msl; the airplane crossed JOXOX at 750 feet.

The decision altitude (DA) for the approach is 789 feet msl. About 1.25 miles from the runway and left of the runway centerline, the airplane impacted and became suspended in a power line tower at about 600 feet msl and 100 feet agl.

MORE QUESTIONS TO ASK

Time again to think about what you’re about to do by asking: Am I ready to fly the approach as charted, closely following lateral and vertical guidance all the way to the MAP, even if I have ground contact? Am I ready to immediately and correctly fly the missed approach procedure at the moment I reach the MAP if the required runway or runway environment cues are not positively in sight, and not second-guess my decision to miss once beginning the procedure, even if the runway comes into view during the missed?

Am I ready to immediately and correctly miss the approach if I reach full-scale deflection of either a lateral (localizer or inbound course) or vertical (glideslope/glidepath) indication prior to going visual? At night especially, am I ready to maintain visual glidepath and/or visual descent point rules after breaking out, to avoid unlit or hard-to-see obstacles on final approach?

Finally, am I ready to immediately take corrective action if I receive a low-altitude advisory from ATC?

AM I READY?

Again, none of the information in the NTSB preliminary report or other accounts of the suspended Mooney are confirmed fact at this time. Some details may be confirmed during the investigation; others may be added and some information thought to be true now may be found to differ under scrutiny. Regardless, the events as we know them now are a good illustration of the cumulative effects of decisions and actions, and the effect human factors may have on the outcome of a flight. They prompt us to consider the possibilities for the flights as we plan and conduct them. Ask yourself repeatedly, “Am I ready for this?” and exercise your escape from the scenario without delay if the answer is anything other than an emphatic “yes.”

Tom Turner is a CFII-MEI who frequently writes and lectures on aviation safety.