It was annual time again for my employer’s A36 Bonanza. It’s worth the trip from our base in Wichita, Kan., to Bob Ripley’s Southern Aero in Griffin, Ga., just south of Atlanta, for his level of expert attention. I chose Birmingham, Ala. (BHM), for a fuel stop; not the cheapest avgas, but one where I could be certain services would be available on a gloomy winter weekend. And I could get there with plenty of fuel for a solid alternate. The airport was directly under a dashed blue line on my iPad marking the western edge of an Airmet for moderate icing from the 5000-foot freezing level and up.

I took off from Wichita with the plan of diverting back to the west if it appeared I was going to enter clouds at or below freezing temperatures or at the first sign of airframe ice (which can form on a cold airplane at temperatures a little above 0 degrees C). The undercast began over central Arkansas and lasted the rest of my trip. Tops were about 5000 feet, and I was in clear skies 2000 feet above that.

ARRIVING

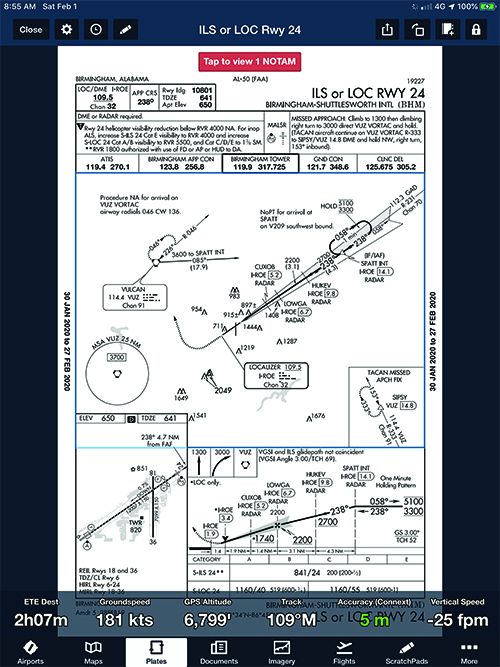

Birmingham was reporting between 600 and 800 overcast, with visibilities as low as 2½ miles, as I checked weather frequently along the way. Arrivals were flying the ILS 24 approach, which offers standard 200-and-a-half minimums, so getting in shouldn’t be too much of a problem. If you fly an approach procedure, however, there’s always the chance you may have to miss it—that’s why an alternate is required when the destination is less than VFR.

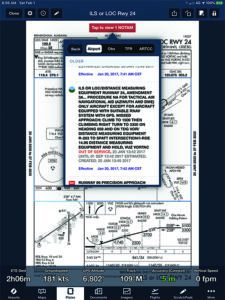

While still over an hour out, I took another look at the ILS 24 procedure to refresh my arrival brief. I had checked Notams before takeoff, and the ILS chart on my ForeFlight display contained a box indicating there was a Notam. It didn’t affect me, but the display had another box, labeled “Older Notams.” I selected these, and the third one down significantly changed my approach briefing.

The charted missed approach procedure is to climb to 1300 MSL, then a climbing right turn to 3000 feet msl direct to the Vulcan Vortac (VUZ) and hold northeast. The turn to VUZ is about a 100-degree heading change, to just west of a northerly heading as shown on the plate at below left. Scrolling down through the older Notams, however, I found the note at below right: The facility was out of service—and still is at this writing.

A revised missed approach was in use: Climb to 1500 feet, then make a climbing right turn to 3300 feet msl on a 058-degree heading and inbound on the 283-degree radial of the Talladega VOR (TDG), then direct to the SPATT intersection and hold northeast. The turn is more than 180 degrees and ends on an easterly heading, and the target altitude is higher. This vital change is hidden several items down on a secondary list of older (but still-in-effect) Notams.

NAVIGATING

This alternate missed approach procedure is not in the Garmin navigation database. Further, SPATT intersection appears on the ILS 24 approach chart but does not appear when you load and activate the ILS approach in vectors-to-final mode—you need to load the full approach and select SPATT as your initial fix to see it on the GPS map. To prepare for the missed approach procedure—a critical part of any approach briefing—you need to be prepared to fly this “old school.”

I dialed Talladega into the #2 nav and spun the OBS to 058 degrees. I then switched it over to the localizer frequency so I could use it and its glideslope to crosscheck the G500 TXi display during descent, ready to swap in TDG after becoming established in climb. Once on the radial inbound, I could call up the GPS flight plan and select “direct to SPATT” and then enter the depicted holding pattern. Up until “direct SPATT,” however, none of the route would appear on the various moving map displays. I could use HDG mode on the GFC600 autopilot if I wanted, but until I was going direct to SPATT the NAV mode was not available.

That’s a whole lot to try to figure out close-in to the airport, or especially upon reaching minimums and finding you need to fly the missed. It’s something you’d best know before you ever leave the ground; in fact, I was able to rehearse the buttonology a couple of times en route.

I checked with ATC and confirmed there were no reports of ice on the approach (the surface temperature was 10 degrees C). It was slightly above freezing when I descended into the clouds on vectors with the ILS full approach selected. I broke out at 1600 feet, almost 1000 feet above field elevation, but I was ready just in case…because I had read all the notations, including a somewhat obscure Notam.

There can be some uncertainty about whether or not a flight may be made with inoperative equipment, but the answer is easy—and the decision isn’t entirely yours. If something on the airplane is not working, FAR 91.213 tells us you can fly only if the inoperative equipment:

• Is not required by regulation for the type of flight operation (VFR, IFR, night, “known icing”).

• Is not listed on an approved Minimum Equipment List (MEL) as required for flight. Remember that there are no “blanket” MELs. An MEL is a one-on-one agreement between a specific operator and the FAA.

• Is not listed on the airplane’s Type Certificate or an STC as required for the type of flight operation.

• Is not listed as required to be operative on a Kinds of Operations and Equipment table in the Limitations section of an Aircraft Flight Manual (AFM) or Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH) for that airplane.

The inoperative equipment also has to be placarded as such and its electrical circuit, if any, disabled.

You cannot choose to fly with inoperative equipment that does not pass this test of requirements. You can, however, be even more conservative if you wish, for example, deciding not to fly without a #2 navcom, even though it’s not required.

LIMITATIONS

On arrival, I shut down between a later-model Piper Saratoga and an Embraer Legacy 6000, the corporate version of the ERJ-145 regional airliner. I watched the fueler top off my company Bonanza, then went into the small FBO. Two casually dressed guys were sitting on couches in the eternal “waiting out the weather” pose. As I sat on a third couch, one of them asked if there was any ice on the approach. I told them there wasn’t and he began asking more questions about weather to the west—they were heading to St. Louis and were noticeably encouraged by my report.

I asked if they were flying the nice-looking Saratoga and the guys laughed. “No, we’re in the Legacy jet,” one said. They had an ice protection system failure that invalidated the personal airliner’s known-ice certification and had been sitting since the day before, waiting to return home. “We don’t usually dress this casually,” one explained, but they had put the jet’s owner on an airliner and were taking it home without passengers as soon as they could. I told them I admired their professionalism in adhering to the airplane’s limitations. “It’s got to be hard to tell the owner of a $25 million jet he has to fly home on Southwest,” I remarked.

EXPECTATIONS

About two hours after landing at BHM, when it appeared icing conditions were moving off and I could complete my flight to Griffin, I filed a flight plan. I’d be in clouds the whole way and wanted to remain below the reported 5000-to-6000-foot freezing level, so I filed via Victor airways that permitted cruise at 4000 feet when off-airways flight would require higher. Yes, I know 4000 feet is wrong for the direction of flight, but that’s negotiable with ATC.

Sure enough, I soon received an “expected clearance” on my iPad that was different from the one I’d filed. With this newest first-world-problem gotcha in mind, I didn’t want to fall into the same trap. I did not amend my filed flight plan. But I did create a second flight plan in ForeFlight using this expected route. After a non-ice-protected Cirrus landed and the pilot reported no ice during his 4000-foot cruise down from Atlanta, I fired up and called for my clearance. Clearance Delivery gave me a full-route clearance that was the “expected” route. The controller read it to me in full, phonetically spelling the intersection names and giving me the applicable VOR identifier. I recognized the names since I’d just loaded them myself. More importantly, all I had to do was select the second flight plan in ForeFlight, forward it to the map display, and then Bluetooth it to the panel. No confusion, ready to go!

I’ve since learned that ForeFlight, and likely other providers as well, give you a button with the option of selecting the filed or expected route when firing up the software for takeoff. So you don’t have to manually load it in. I find loading it myself, however, helps prepare me for the possibility of the second routing.

DEVIATIONS

Bob Ripley’s shop is at the small, private Cedar Ridge airport about seven miles west of the Griffin Spaulding Airport and has no instrument approaches. Overcast ceilings in the Atlanta area were about 1900 feet, so my plan was to fly the RNAV GPS 32 approach into Spaulding, cancel IFR when 500 feet below the bases, tap the Cedar Ridge identifier into the GTN 750 and proceed VFR to land. That almost worked.

I indeed did break out at about 1900 feet agl, with visibility of about five miles in haze. With the runway in sight, I cancelled IFR and tapped GA62 into the GPS, but the identifier wasn’t recognized. I tried again and got the same result. The box asked if I wanted to add a waypoint and I was tempted to try. But I was at about 1000 agl, coming down the LPV glidepath, and it was the better option to simply land and figure it out at zero groundspeed, one G and zero agl.

Bob later told me that despite their efforts, Cedar Ridge no longer appears in the Garmin airports database (it had before). It does, however, show up on ForeFlight, so I was able to make the very short VFR hop after plotting it out on my iPad on the ground. The biggest anomaly is that the G500 TXi’s synthetic vision was flashing red and screaming “Terrain, Terrain!” at me on final approach to GA62, because it did not recognize I was descending toward a runway. I’ll see if adding GA62 as a user waypoint runway fixes that when I pick the Bonanza up after its annual. Meanwhile, that’s one more distraction to prepare for in the event I ever need to make an off-airport emergency landing.

Well-practiced stick-and-rudder skills and familiarity with the avionics and autopilot made the trip toward annual inspection easy. The challenge was in the planning, preparation and execution of decisions in the system. You may have done things differently under the same circumstances, but whatever you do, make informed choices.