One of the benefits (and frequent challenges) of flying IFR is operating under positive ATC guidance and control. If you are operating only at towered airports, this is fairly simple. Clearance or ground control will issue your clearance, and when you land safely at your destination, they will make sure to close your flight plan. Depending on where you fly, though, being under ATC’s watchful eye from takeoff to touchdown may be a luxury.

Most of these benefits/challenges still can be obtained when at least one airport in your flight plan is non-towered but—since you’ll be on your own for a portion of the flight—there are some differences and extra steps worth reviewing. Perhaps most important is the possible presence of VFR traffic, but some rules also change.

DEPARTURES

One of the first steps of any IFR flight is picking up a clearance. There are a number of methods for doing this, and all of them depend on the departure airport’s facilities. Let’s talk about the most common options and considerations.

Frequency: I mention this one first, because it aligns the closest to towered operations. If a frequency is available, it will be listed in the chart supplement and on the approach plates. If this is the case, it’s business as usual. Occasionally, airports with a closed tower will have some additional stipulations, which can be found by listening to the remarks on the AWOS/ASOS. An example of this would be transmitting on one frequency and listening on another, which could be a navaid capable of voice transmission. Seems complicated, but it works just like identifying a navaid in flight or listening to Flight Service over a VOR. Instead of Morse code, you will receive a clearance.

Phone number: In 2019, the FAA completed its Clearance Relay Initiative. To cut out the FSS middleman, the FAA has provided phone numbers for each airport published in the Chart Supplement to the appropriate ATC facility. One of the great benefits of having a Bluetooth-capable headset is the ability to call with the engine running, but there are a number of creative solutions if your headset isn’t compatible. I have seen many impressive maneuvers involving a cellphone underneath a headset that artfully cut off noise while still allowing the pilot to talk and hear the call.

Void time: With both of these options, there is one more step to navigate prior to departure: the clearance void time. My preference is to call and get my clearance prior to engine start, so I can ensure my flight planning was correct and no unexpected route or altitude changes were assigned. Plus, you save some fuel not plugging everything in with the engine running.

On the other hand, there is nothing wrong with getting the clearance after engine start, typically while holding short of the runway. The benefit of doing it this way is you can receive your clearance void time and transition right into the departure. If you elect to get it early, you will have to call ATC back and advise them you are number one for departure. Either way, there may be other traffic in the area, which means you’ll be held on the ground until the potential conflict is resolved. Remember: VFR minimums in Class G airspace during the day is one statute mile and clear of clouds below 1200 feet agl. You may be going IFR for a myriad of reasons, but there could be VFR traffic in the pattern that needs to be accounted for.

Plan to get your void time when you can actually depart, because typically ATC wants you entering controlled airspace within five minutes, and if the airspace is busy, it can be fewer. Pilots are (typically) understanding if you politely ask the aircraft doing touch-and-goes for a brief window to depart, usually they will give it to you. If ATC gives you a void time and you decide you cannot make it, let them know ASAP as they are reserving the airspace for you. You’ll just have to call back when the timing looks better.

Depart VFR/Airborne pickup: If your departure point and initial part of your route are VFR, departing VFR is a great option to avoid some of those challenges. Instead of listing the non-towered departure airport as the first fix, file the flight plan to begin at an airborne pickup point, like the nearest VOR. Pick a point along your planned route that is well prior to any marginal weather.

Keep in mind that issuing IFR clearances to airborne VFR aircraft is near the bottom of the priority list for ATC, so ask nicely. Additionally, getting VFR flight following first and giving ATC plenty of notice will help grease the wheels. Giving yourself plenty of time allows you to strategically make your request when ATC is at a lower workload, and gives you options on the rare occasion where you may be told no.

Photo Credit: Paul Sanchez

One of the easier pitfalls when departing or arriving a non-towered airport is utilizing IFR phraseology that VFR pilots may not be aware of. Fixes, headings or depicted procedures (such as a published missed) are not always the most effective indicators of your position to traffic. Instead of declaring that you are at the final approach fix or procedure turn inbound, give your distance to the runway. If it’s a busy day, throw in your intentions for landing or going missed if you are doing practice approaches.

In addition, something else to be considered are the different types of traffic you may encounter. It is still perfectly legal to operate aircraft without radios in Class G airspace and the traffic tends to be more eclectic at non-towered airports. Have you reviewed the right-of-way regulations recently?

The FAA’s Advisory Circular AC 90-66B, Non-Towered Flight Operations, specifically states that, “Pilots conducting instrument approaches in visual meteorological conditions (VMC) should be particularly alert for other aircraft in the pattern so as to avoid interrupting the flow of traffic and should bear in mind they do not have priority over other VFR traffic.” This is especially true when the approach allows a straight-in landing. Obviously, if the weather is down at minimums, you must have faith everyone else is doing the right thing, but it does not hurt to stay diligent. It also doesn’t hurt to put the destination’s CTAF on the standby radio and listen for traffic well before ATC turns you loose.

DEPARTING IN IMC

I know we just discussed an airborne pickup, but let’s rewind a little and assume the non-towered departure airport is IMC. There are several potential threats that merit mentioning. For one, remember that ATC does not assume responsibility for traffic separation until you are in radar contact in controlled airspace. It is easy to get into the IFR mindset on the ground, but vigilance is still crucial. Especially if you are switching back and forth from the clearance frequency to CTAF and plugging in your route or squawk code, even a momentary loss of situational awareness could be costly.

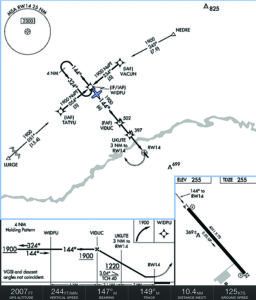

Another critical aspect of the departure is that ATC does not assume responsibility for is obstruction clearance. Recent issues have discussed ODPs at length, so I will not beat a dead horse. Part of your preflight planning should be reviewing the intended runway of departure, ensuring you can meet the required climb gradient and following the ODP.

It does not hurt to have a contingency in the case of an abnormality or emergency, especially since FAR Part 91 does not prevent you from taking off from an airport you cannot return to. If you are unfamiliar with the terrain, using satellite maps in conjunction with charts can show a great deal of options. Having a plan for either a safe return or a diversion airport reasonably close can help mitigate the severity of a potential emergency.

One of the most common platitudes regarding multi-engine airplanes is “all the second engine does is fly you to the scene of the accident.” While I do not support this very defeatist attitude, unfortunately there is some data to support it. Consider the accident history over the last decade of the popular King Air series, with four fatal loss-of-control accidents on takeoff alone. While it is a safety buffer to have a second engine, it requires additional planning.

In this article’s main text, I discuss having a plan for abnormalities or emergencies. An engine failure after takeoff is one of the exact scenarios I had in mind. Light twins typically climb pretty well on both engines, so it is easy to overlook the climb gradients in the ODPs. But if you had an engine failure, could you still meet that climb? Can you re-enter the pattern visually? At a non-towered airport, you will not have ATC to fall back on for guidance.

An engine failure in a piston twin is already a high-workload event and a bona fide emergency without worrying about creating alternate departure procedures for terrain avoidance on the fly. A little preflight planning will go a long way, especially in an unfamiliar environment.

ARRIVALS

I’m the type of pilot who always files an alternate, but situations arise where it may not be prudent to do so, and FAR 91.169 is always worth reviewing. It is simple to comply with it if the non-towered destination airport has an AWOS/ASOS, but what if there’s no weather reporting? The verbiage of the regulation is “…appropriate weather reports or weather forecasts, or a combination of them.” You can use a TAF, but technically their intended use is five nm from the airport. Any CFIIs reading this are probably ahead of me already: The often-forgotten area forecasts are a great tool to get general information about your route and destination, especially for broad planning like alternate requirements.

The foregoing presumes a standard (i.e., published) or special (non-published/private) approach procedure exists for the destination airport. If there isn’t one, you have to file an alternate even if the weather is clear and a million. If there is any doubt, choose and file an alternate. The worst-case scenario is you may need a fuel stop, which is an excellent opportunity to visit a new-to-you airport.

GETTING THE HANDOFF

If your arrival airport is IFR and you need to shoot the approach, ATC will give you a means of canceling prior to switching you to advisory frequencies. Just like getting a clearance, it could be a frequency, phone number or, if someone is waiting in line in the hold, they may have you relay your cancellation through another aircraft. If the weather allows a visual approach, you can cancel in the air. My personal rule of thumb for this is I will only cancel if I can safely re-enter a visual traffic pattern after a missed approach. I do not want to cancel, only to have to execute the published missed and be forced to call ATC, asking for a local IFR. Don’t get me wrong—if this situation occurred, I would absolutely get a pop-up, but it is not preferred.

If I determine I must shoot the approach, that is all I am thinking about it. It does not matter if another aircraft is waiting for me in the hold; I am not concerned with canceling until I am clear of the landing runway. I try to set a trigger to remind myself to cancel, because it is an easy thing to forget, especially if you are accustomed to towered operations. I have picked up a few tips over the years to help remedy this. The easiest one is to associate canceling with the “clear of runway” call. Clear the runway, come to a stop and seal the deal. A few others including taking off your watch and hanging it on the yoke or drawing a big O on your scratchpad. That way if I shut down and I do not have my watch on or there isn’t a line through my O, I know I left the poor guy or gal in the hold hanging.

Thanks in large part to WAAS-enhanced GPS, it’s not uncommon to find minimums as low as 200 feet at a non-towered destination airport. But it’s also not uncommon for a non-towered airport to have no published approach procedure. How can you get in when the weather’s IFR?

That depends on what ATC’s minimum vectoring altitude (MVA) is for that sector, something that isn’t published. If the ceiling is low and you suspect you might not get in, the best bet is to ask the controller about the MVA and when/whether you can expect to be cleared to that altitude. Sooner is better, since there might be good VMC underneath the clouds and the MVA high enough that you can cancel in the air and land VFR. Keep in mind the MVA might be lower if you’re arriving from a different direction. In our experience, ATC usually will work with you if they’re not too busy. If you can’t get in, go to an alternate and try again later.

One gotcha is canceling IFR while still in Class E airspace and conditions less than VFR. You might think it’s a technicality, but that’s something FAA inspectors live for. —J.B.

CLEAR OF ALL RUNWAYS

My intention with this article is not to scare anyone away from non-towered airports. With a little planning and consideration, these operations can absolutely be conducted with minimum additional risk. I am one to preach training and practice, and this is no different. Since six approaches are required every six months anyway (or an IPC), why not show some non-towered airports some love? If you typically maintain currency doing practice approaches VFR, try picking up a clearance just for the practice. A little experience and the resulting higher comfort level goes a long way, even if your typical mission does not involve non-towered airports.

Ryan Motte is a Massachusetts-based Part 135 pilot, flight instructor and check airman. He moonlights as Director of Safety when he isn’t flying.