In an ideal world, upon reaching our decision altitude/height (DA or DH) or missed approach point (MAP), there would always be beautiful visibility and a clear runway. As we all know, life throws curveballs. A classic curveball in instrument flying can be a missed approach. Preparation is worth an ounce of cure, and these tips will help you stay ahead of the airplane during a missed approach.

Whenever I find myself in flight and behind the airplane, I always try to thoroughly brief the facts, conditions and circumstances that led to that condition. After all, mistakes can be some of our greatest teachable moments. I found myself behind the airplane one day, and it inspired the topic of this very article.

ROUTINE COMPLACENCY

I was flying into a fairly busy airport near New York City. It was a routine flight, and actually our second trip into the airport that day, flying the same approach into the same runway. The weather was decent: 1000-foot ceilings and more than 10 miles of visibility underneath. Low enough so everyone was shooting approaches, but high enough they were getting in. Sounds ripe for some complacency, doesn’t it?

We broke out at 1000 feet msl, right on schedule. At this point, I think our focus transitioned from the approach to the landing and taxi in. There must have been some confusion on the ground frequency, because an aircraft crossed the active runway when we were at around 100 feet or so agl. Naturally, we went missed.

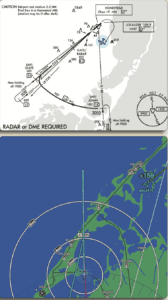

The tower controller seemed as surprised as we were, as they initially told us to fly runway heading before assigning the miss as published. There was some initial confusion; the GPS didn’t sync properly and I had to look at the approach plate to figure out the initial turn. We got there eventually, but I really was not a fan of that initial feeling of uncertainty. I adopted the following tips and tricks to help avoid falling behind the airplane during a missed approach.

CONTINUATION BIAS

There are a couple of threats to manage when considering missed approaches. There really is not a requirement to ever practice them, so long as you maintain instrument currency. A CFII worth their salt will ensure it is covered in an IPC, but many times a challenging miss can be hard to come by, since ATC may provide vectors to make life easier, and the published miss can interrupt their traffic flow. Many instrument pilots wisely set personal minimums well above approach minimums, meaning a naturally occurring missed approach is rare.

Additionally, a missed approach is almost always unexpected. Most pilots will not intentionally initiate an approach if the weather is below minimums. If the weather is at or just above minimums, continuation bias leads pilots to focus more on the landing, which is the desired outcome, rather than the undesired missed approach. How can we fight this issue of continuation bias and potential lack of recent experience?

Modern technically advanced aircraft often have helpful navigation tools. A flight director can help a pilot manage the flight path effectively, especially in high-performance aircraft. But just like any other risk mitigation tool, it needs to be managed. Typically there is some sort of TO/GA(takeoff/go-around) button that triggers the flight director to pitch up and resets the lateral navigation. It’s critical to ensure that if your intention is to follow the flight director, said lateral navigation is correctly set. In a busy missed approach procedure, that step can be overlooked and the pilot will be happily following the flight director, which may not be providing any actual guidance.

This may not be the case with all avionics packages, but if both are installed, typically the autopilot will use pitch and bank to keep the aircraft the flight director’s parameters. Confirm with the manufacturer’s guidance, but if you can use the autopilot for the approach and through the missed, the above step becomes even more important. If there is an error, best practices are to step the automation down until it is performing as expected. This may mean going from NAV to HDG mode, or disconnecting the autopilot altogether and hand-flying.

TWO ROADS DIVERGE

The ideal outcome for an approach outside the training environment is a landing and taxi to parking. Sometimes, we end up at a holding fix exploring options. Briefing and planning the miss is the first step in effective execution. Knowing the initial heading or track and at what altitude to level off is a great start. As often as not, ATC gives simple alternate missed approach instructions (“runway heading, maintain 3000,” anyone?), but it can never be counted on.

There is a lot going on while shooting an approach, and many missed approaches are complicated. The miss does not need to be committed to memory, but covering the steps required during the briefing helps keep everyone ahead of the airplane. Long story short, brief and expect the miss every time.

PRIOR PROPER PREVENTION

Step two also occurs well before the actual miss. This will vary from aircraft to aircraft, even from panel layout to panel layout. Staying ahead on frequencies helps. I have noticed pilots tune the ground frequency once they have made positive contact with tower. This is a fine technique but will increase workload if a miss does occur. If your aircraft has two radios, you can also use that to your advantage.

The two single most important tasks during a missed approach are getting the aircraft away from the ground and pointed in the right direction. We will discuss getting away from the ground shortly. Getting the aircraft pointed in the right direction can involve a few steps, depending on aircraft capability and automation levels. Starting from the most basic levels, non-GPS aircraft will mostly likely have to swap navigation frequencies and tune a radial to intercept. Again, backup frequencies or even backup nav antennas can be really helpful here. Aircraft with an IFR-approved GPS on board can help simplify a miss, especially using GPS accuracy to replace something like a VOR radial to intercept a holding fix off of another VOR. Knowing your avionics is key. I frequently see issues with advanced avionics where something can be slightly amiss and the result is improper guidance, which often isn’t detected until said guidance is required.

For example, many pilots elect to use their Garmin to provide lateral guidance on the missed approach. This is a great technique and can reduce pilot workload. But issues can arise if the GPS is not sequenced correctly. The following scenario may seem unlikely, but it has happened to me multiple times and will result in most Garmin products (and pretty much every GPS/FMS I have utilized) failing to provide any guidance during the miss.

Prior to the approach, ATC assigns direct to one of the approach’s initial approach fixes (IAFs). You properly load this into your GPS and proceed direct to the IAF. Then, ATC starts giving you vectors to final to save everyone some time and gas. The GPS is still direct to the IAF, which is now behind the flight path. At this point, many pilots would switch their navigation source from GPS/FMS to ground-based navaids, which would accurately track the ILS.

At the MAP, the pilot presses the OBS button to take the GPS out of SUSP mode and sequence the miss. The only problem? The GPS is still programmed for direct to the IAF and does not provide accurate guidance. A savvy pilot might be able to select direct to the first fix on the miss, or otherwise tune and set everything required. This increases cockpit activity in an already extremely high workload environment. Being comfortable with your avionics and ensuring they are sequenced correctly can keep you ahead of the airplane, as may activating vectors-to-final outside the final approach fix (FAF).

If you are flying a precision (or precision-like) approach to a decision altitude (DA) or decision height (DH), you make the decision to continue or go missed at the altitude listed on the approach plate. If it has been a while, it is worth reviewing FAR 91.175, Takeoff and Landing Under IFR. There are three main components:

Airport environment

You need one or more items of the airport environment listed in the regulation in sight. If you just have the approach lights, such as the sequenced flashing lights, you can descend to 100 feet above the touchdown zone elevation (TDZE). I have never descended to 100 above TDZE and not caught the airport, but you never know.

Visibility

You need visibility at or above that prescribed on the approach plate. There are literal seconds to make this decision, so having an idea of what you are looking for is helpful. For example, ALS lighting on precision approaches extends 2400-3000 feet beyond the threshold. The thousand-foot markers can also provide a good snapshot of in-flight visibility.

Normal Maneuvers

The aircraft must be in a position to make a landing with normal maneuvers. No getting the runway in sight and diving to the runway. Additionally, it does happen where you catch the environment after the miss has been initiated. Once the safe decision has been made to go missed, stick with it. Odds are the weather is improving, and the next approach will have better luck.

All this is true for a non-precision approach with a minimum descent altitude (MDA). Upon arriving at MDA, there is no immediate decision to be made. The flight can continue to the MAP listed on the chart. The biggest consideration at this point is using normal maneuvers. If the MDA is 1000 feet agl and the runway environment comes into sight a mile out, is it possible to make that runway using normal maneuvers? Keep in mind any visual descent points (VDPs) discovered in your preflight planning and remember that stabilized approaches are good practice in any aircraft.

EXECUTION

I was taught the so-called “5Cs” for going missed. Even if you were taught a different mnemonic or technique, this is a nice way to outline the steps and discuss common errors. They are: Cram, Climb, Clean, Click, Call. The sidebar at right hits the highlights, but let’s also dive down a little bit

Cram: Add full or takeoff power. This may seem self-explanatory, but I have seen near-stall conditions low to the ground because of improper power management on the miss. It also emphasizes the order, which can happen concurrently for the most part, but it rarely is a great idea to add back pressure without first adding power.

Climb: Again, seems obvious, right? It is not uncommon to have an unexpected miss and have students level off and complete additional steps prior to climbing. Obstacle clearance is predicated on a 200 feet/nm climb rate, unless otherwise stated on the approach plate. Getting to VX or VY as soon as possible after initiating the miss will ensure this gradient is met, so long as the aircraft and environment allow.

Knowing a general pitch setting can help point the aircraft in the right direction without getting too slow. Common errors run from not initiating a climb at all to pitching up so much intervention is required. Especially in low visibility, transitioning from an approach attitude to a missed approach attitude can cause spatial disorientation.

Clean: Configure the aircraft per the manufacturer’s recommendations for best climb. Remember to keep pitch angle, airspeed and AoA in mind, because bringing flaps up can drastically increase stall speed.

Click: This refers to sequencing the miss. As discussed earlier, it could be hitting something on the GPS, swapping nav frequencies, moving the heading bug, etc. The challenge here is doing this, while managing everything above. Especially if something is amiss, the main focus should be managing the aircraft.

Any time there are terrain concerns on the miss, extra consideration should be taken. Occasionally I will be flying with someone, and their GPS will be sequenced incorrectly or the radio nav aids are not set up for a miss. “I will just ask ATC for vectors,” is the prototypical get-out-of-jail-free card. While this is a good use of CRM in an abnormal situation, it should not be relied upon. There are times where you will be below the minimum vectoring altitude and potentially even below radio coverage.

Call: Let ATC back into the loop. One way or the other, they are waiting to hear from you, and odds are you will want their service.

Cram

Add full or takeoff power to initiate the missed approach. This should be first because, if trimmed correctly, the airplane will seek the same airspeed, which at full power should result in a climb.

Climb

Ensure the airplane is climbing, putting distance between it and the terrain.

Clean

The airplane undoubtedly will climb better when it’s properly configured, so clean it up. Don’t forget to enrichen the mixture and open cowl flaps, if so equipped.

Click

Push whatever buttons you need to bring the avionics into the game, hopefully only requiring one stab at the OBS button to sequence the missed approach procedure

Call

Once you’ve ensured the airplane is climbing, configured and navigating the miss, it’s time to give ATC the bad news.

BASIC PRINCIPLES

Some of this is just aviate, navigate, communicate broken down specifically for a missed approach. Some principles of aviation just always ring true. Prepping and anticipating the miss is great; going out and practicing is even better.

Staying ahead of the airplane often involves planning for multiple contingencies, and when shooting an approach, the miss is always one of those contingencies. My goal is that nobody reading this will ever hear the dreaded, “Go around, and fly the miss as published,” and end up as behind the aircraft as I was.

Ryan Motte is a Massachusetts-based Part 135 pilot, flight instructor and check airman. He moonlights as Director of Safety when he isn’t flying.