Growing up in the pre-9/11 era, I was fortunate to take international family vacations. Going through a commercial airport without TSA, high-sensitivity metal detectors and the spirit-deadening routines of today is something I never thought would have happened. September 11, 2001, was a turning point, of course, and governments worldwide responded, forcing flight and ground crews, and passengers, of course, to change the way they looked at securing themselves when traveling by air. One result is that those of a certain age don’t know what it’s like going to the airport without all these precautions in place. When they have an opportunity to use a general aviation airport, they’re often astonished at the freedom of movement. So why is any of this important to you?

Anyone flying from non-commercial facilities will notice that security is much more relaxed. Each airport has their security procedures, which include collaboration with ATC if the airport has a tower. In addition, fixed-based operators have their own security procedures. How about the airports that do not have a control tower or may be run by a small airport operations staff? The thing is, pilots are on the front lines of general aviation security. Yes, airport operations and ATC can also play a role but the security of the national airspace system and general aviation airports rests on the shoulders of pilots, especially when it comes to reporting suspicious activity. As a pilot, what can you do to make sure your flying experience, airport and aircraft are secure?

STATE OF MIND

Merriam-Webster defines security as “the quality or state” of being free from danger and from fear or anxiety, ultimately meaning that security is merely an idea, a feeling. The term “security theater” was coined in the aftermath of 9/11 to describe the concept of the TSA doing something with dubious actual value but also with the appearance of doing something to make people feel more secure. Outside the airport terminal, security depends on how well you secure yourself and property by means of locks, cameras, alarms, procedures and consistency. Finding methods to deter those individuals or situations that can lead to infringing your security will limit how unsafe you feel.

Which leaves me amazed when a few pilots I know leave their hangar doors unlocked. Even if you fly out of a small airport where everyone knows you, it still is not the best idea to leave your hangar subject to mischief like this. At my usual airport, individuals have been encountered walking up and down the rows of aircraft, asking pilots random questions that make them feel uneasy. Many smaller airports have little physical security, even when fencing and gates are employed. For example, there’s usually some method to gain access, even in broad daylight, like punching in the airport’s CTAF on the vehicle gate’s keypad.

While there’s no way to protect ourselves, airplanes and hangars from every possible event, don’t believe that any situation is too far-fetched to happen. Just as when we’re airborne, anything is possible. And malice isn’t required, especially when someone not familiar with aviation is involved. You would think that would be a no-brainer, but it sometimes isn’t. A recent event at my airport involved an individual participating in a photo shoot who was allowed on the airfield, despite not knowing at which hangar to meet their other party. The individual drove across the runways and taxiways without talking to anyone in search of where to go.

When you grant people access to the airport, you also are taking responsibility for them while on the airfield. Make sure non-pilots receive a briefing of what to expect, non-movement areas and just common sense while being on the airport. As someone utilizing the airport, it helps to be familiar with it. Often some kind of map is available from airport operations. Understand and respect that certain security procedures should not be made public.

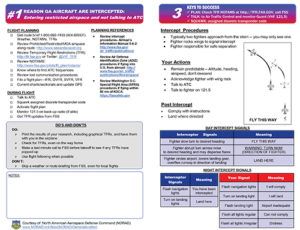

Lastly, do not hesitate or be afraid to report suspicious people, packages or aircraft. Reporting people would constitute people walking up and down aircraft with unusual behavior. Anything that seems out of place, is a safety issue or hazardous should be reported to a responsible party.

In the days immediately following the 9/11 attacks, everything except aircraft engaged in national security was grounded. First, limited non-scheduled IFR flights were allowed, followed by airline operations subject to invasive security. Something known as “enhanced Class B” airspace was created and temporary flight restrictions (TFRs) blossomed like dandelions on a lawn. Soon thereafter, VFR operations were allowed.

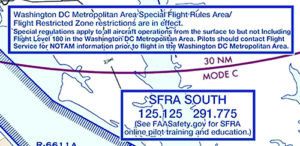

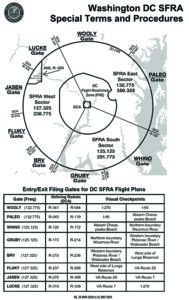

Eventually a lot of the hysteria and associated restrictions, at least as far as general aviation was involved, subsided. Yet the airspace itself remains a focus, implemented by better-defined TFRs throughout the U.S. and the Washington DC Special Flight Rules Area (SFRA). The Disneyland and Disney World sites got special, Congressional attention, and major events like sports and conventions are subject to hot and cold TFRs.

Early on, getting accurate, timely information on TFRs involved logical contradictions: We can’t tell you where they are because security, but avoid them anyway. Calling your local Flight Service Station—remember them?—for the latest information right before takeoff was a thing. Pilots who did so were not immune to an FAA violation if they entered a TFR that didn’t exist when they took off.

These days, the electronic flight bags we all seem to use typically plot TFRs for us, based on the Notam establishing them. The one constant is the DC SFRA, which now has its own place in the FARs requiring free online training to be completed before flying within 60 nm. The images at right depict the SFRA and some of its charted warnings. For more information on the SFRA and required training, see FAR 91.161. — J.B.

MORE TO DO

One characteristic of a well-managed airport is involving the pilot community on a regular basis. Monthly or quarterly meetings can go a long way toward fostering understanding and cooperation, and allow both management and users to become familiar with the people using and operating the facility. Knowing the people they regularly encounter is a boon to management and simplifies many of its tasks. Keeping everyone informed and talking to each other helps promote safety and security at local airports airport.

That said, nothing is foolproof or immune to those who would cause mischief. Aircraft and vandalism do happen, and your new avionics stack may be a prime target for thieves. Making their task more difficult, time-consuming and exposed to detection is in your benefit, since at some point they’ll just move on to a nearby airport without the obvious complications.

In addition to securing your hangar, be responsible in securing your aircraft keys. Some pilots leave their keys in the hangar, easily accessible, while some even leave them in the aircraft. Conspicuously placed video cameras—inside and outside your hangar—might work to thwart thieves, or at least allow you to identify who walked away with your iPad.

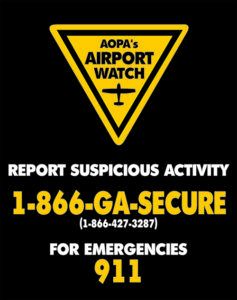

If you’ve spent much time at a GA airport in the last 20 years or so, you’ve probably seen the sign at right before. In part, it was a response to policymakers who wanted general aviation to take more seriously what they considered to be continuing gaps in national security, even if the facilities themselves and the airplanes using them posed very little threat to anyone. On one level, AOPA’s Airport Watch program was created to forestall onerous restrictions and, perhaps ultimately, airline-style security screening.

The then-fledgling TSA instead created a set of security guidelines for GA airports “based on the general aviation community’s analysis of perceived threats, areas of vulnerability, and risk assessments.” It is not a regulatory document and its guidance should not be considered mandatory. It is separate from other TSA security programs (i.e., the “Twelve-Five Rule”).

The guidelines offer “options, ideas, and suggestions for airport owners, operators, sponsors, and other entities charged with oversight of GA airports.” The guidelines are available online as a 56-page PDF, free for the download, at tinyurl.com/SAF-TSA. — J.B.

USE YOUR HEAD

Most of the topics in this magazine and elsewhere involving aviation safety are focused on what happens in the air while not much of what happens on the ground before and after each flight is discussed. Which is odd, because keeping you and your airplane safe are the very first steps of a successful flight. When considering passengers and, especially, airport visitors who haven’t been briefed on what to expect and what to avoid, the burden often is on us to manage their activities and expectations.

Use your head and be aware of what’s going on around you. Know the people you fly with, know the flight school employees, know your airport operations staff and take the time to introduce yourself to the people who work in the tower. The airport community must support each other and help ensure everyone’s safety—no one’s going to do it for us.

All in all, be aware and know your surroundings. A fence can only do so much. If asked for your identification do not take offense. Personnel from the FAA will have a badge displayed on a lanyard while law enforcement will have a badge or agency ID card. If you feel suspicious about a person asking for your ID have them show you their badge or credentials first.

The AOPA’s Airport Watch program (see the sidebar at the top of the opposite page) deserves our support and is important, if for no other reason than to forestall other, possibly more-onerous security programs. Finally, don’t confuse aviation security with aviation safety, which some seem to use interchangeably. Safety involves the operation of an aircraft while security involves preserving it for another day.

Safe (and secure) flying!

Readers familiar with this magazine’s overall theme—risk management—should know the Department of Homeland Security has adopted the same principles in its operations:

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the TSA’s parent agency, defines risk as “the potential for an adverse outcome assessed as a function of hazards/threats, vulnerabilities, and consequences;” using a consistent set of definitions for these terms:

“Threat: A natural or human-created occurrence which includes capabilities, intentions, and attack methods of adversaries used to exploit circumstances or occurrences with the intent to cause harm.

Vulnerability: A physical feature or operational attribute that renders an entity open to exploitation or susceptible to a given hazard.

Consequence: The effect of an event, incident, or occurrence.”