If you’re not familiar with Alaskan aviation, an analogy might be to compare it to operations in the Lower 48, but with more weather and terrain, and fewer paved airports. Because general aviation often is literally the only transportation available, external pressures to complete a proposed flight can be much greater. Predictably, the accident rates for both Part 91 and Part 135 operations are higher. And when it comes to aeronautical decision-making, one of the predominant myths associated with Alaskan aviation safety is that commercial accidents most commonly occur here because a young, inexperienced pilot from the Lower 48 was in the cockpit. Regardless of what the data reveals—in the last decade, the average PIC flight time for Part 135-involved accidents was about 9500 hours—the myth persists that pilot inexperience is at the root of poor decision-making.

A deeper look behind two accidents that are striking in their similarity, however, shows pilots with vastly different flight time can still find themselves in the same tragic circumstances. The crashes of Wings of Alaska and Taquan Air Service, which occurred in the same region three years apart, are an object lesson in why the root causes of Alaska’s chronically high accident statistics are much more complex than they appear.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

In the summers of 2015 and 2018, Wings of Alaska and Taquan Air were Part 135 operators flying single-engine aircraft, VFR-only in Southeast Alaska. Taquan was based in Ketchikan and Wings in Juneau, although its owner and source of operational control, SeaPort Airlines, was based in Portland, Oregon. The NTSB found the same primary probable cause in accidents involving both companies: the pilot’s decision to fly VFR into IMC. In the 2015 Wings accident, the pilot was killed and four passengers were seriously injured. In 2018’s Taquan Air accident, six passengers received serious injuries and four received minor injuries.

The Wings flight was scheduled, in a Cessna 207A, while Taquan operated a de Havilland DHC-3 Otter on floats flying a charter for a local lodge. Both companies had long histories operating in Southeast Alaska, and both were members and “star” recipients of an independent statewide safety organization, the Medallion Foundation. Medallion was heavily financed and supported by the FAA, and its membership advertised as having “higher standards of safety than required by regulations.”

Close inspection of the final reports reveals a glaring difference between the two accidents: The Wings pilot had 840 total hours of flight time with about 68 hours in Alaska while the Taquan pilot had 27,618 hours total time with 2700 hours of experience in the state. Yet despite their starkly different degrees of experience, they both did the same thing: impact mountainous terrain in poor weather. The story of how they each got there can be found in the documentation of a litany of missed opportunities which reaches back beyond the cockpits and into decisions made months earlier by Wings and Taquan management, and the FAA.

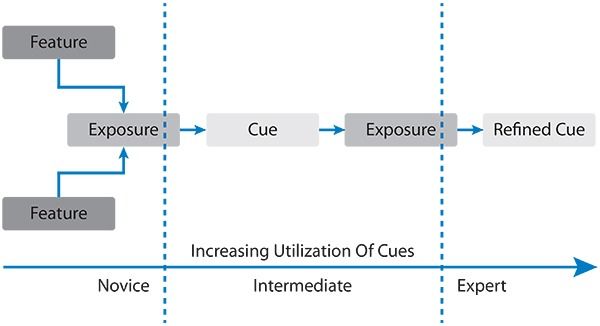

In cue-based training, pilots flying VFR along regular routes are formally taught to recognize certain physical features that serve as cues proving visibility standards are being maintained. If a cue is not visible, then the pilot is to turn around. Following the crash of a multiple-fatality Taquan Air Service air tour flight on July 24, 2007, the NTSB issued four safety recommendations to the FAA. Two of them referred directly to cue-based training.

In recommendation A-08-061, the FAA was charged to develop, in a coordinated effort, “a cue-based training program for commercial air tour pilots in Southeast Alaska that specifically addresses hazardous aspects of local weather phenomena and in-flight decision-making.” In recommendation A-08-062, the agency was informed that once this program was developed, it must “require all commercial air tour operators in Southeast Alaska to provide initial and recurrent training in these subjects to their pilots.” Cue-based training also is in use among Hawaii-based tour operators.

Taquan Air did develop a cue-based training program, but the Jumbo Mountain flight cited in this article did not adhere to it because, according to the company, it was not a tour flight. According to NTSB interviews, Wings of Alaska did not develop a program at all.

A 20-MINUTE FLIGHT

Wings of Alaska Flight 202 was scheduled on July 17, from Juneau to the village of Hoonah, on Chichagof Island, a 20-minute flight across Northern Lynn Canal. The company had cancelled most flights to Hoonah that morning due to weather. Flight 202 was scheduled to depart at 1300. Prior to going off duty, the company flight coordinator in Portland advised the Flight 202 pilot to speak about the weather with the pilot who had just returned. (The NTSB had no record of this conversation taking place.) No one from operations spoke to her again until she reported taxiing out for departure. The company’s required risk management assessment form was left in Juneau and not faxed, as required, to Portland. No one saw it until after the accident.

The flight was cleared for takeoff at 1308. Fifteen minutes later, a passenger contacted Juneau police dispatchers via 911 and reported the crash. The wreckage was located at about the 1250-foot level just north of Point Howard.

The weather in Juneau 10 minutes prior to takeoff included seven miles’ visibility in light rain and mist with few clouds at 200 feet and an overcast at 3500 feet. A weather camera at the Juneau airport showed a wall of rain, fog and mist in the direction of Hoonah. According to a passenger who spoke to the NTSB, the flight encountered turbulence shortly after takeoff, along with multiple layers of clouds and fog. He believed the pilot was attempting to fly between the layers when they hit the mountainous terrain.

As the investigation commenced, the NTSB found conflicting answers from company pilots and management as to the minimum en route altitudes over water, with figures ranging from 500 to 1800 feet. SeaPort’s Director of Operations (DO) went so far as to say that minimum altitudes “depended on a particular flight” and stressed the decision resided with the pilot. He did not have any knowledge of any flight training for required gliding distance over water. The Chief Pilot, who had not been to Alaska in almost a year and was not current in the Cessna 207, said he did not believe that minimum altitudes for any company flights were documented in the training manual.

Another issue investigators documented was operational control. SeaPort’s flight coordinators were unclear as to their required duties although the DO asserted they were responsible for operational control. Meanwhile, the company president stated there was no training program for the flight coordinators. None of the interviewed coordinators knew what to do with the risk assessment forms faxed from Juneau or even if they were supposed to be obtained prior to a flight’s departure.

The NTSB found that beyond the Flight 202 pilot’s decision to fly VFR into IMC, contributing factors were the company’s poor training and oversight of operational control personnel and failure to follow its own operational control and flight release procedures (i.e., the risk assessment forms). The FAA was also faulted for failure to require SeaPort to correct known deficiencies and ensure that it complied with its operational control procedures.

There are 230 FAA-maintained weather cameras in Alaska, sited at various airports and locations throughout the state. These cameras, part of a 20-year-long program, are accessible online and provide critical information, particularly from remote areas where there is little or no weather reporting available. They are especially valuable in the Southeast part of the state, site of the most remote camera locations in the system, 52 water-miles from Ketchikan and deep within the Misty Fjords National Monument. There is a significant amount of seasonal flying in Misty Fjords, both sightseeing and to remote lodges, and the cameras are crucial to risk-assessment decisions.

Following its long success in Alaska, the FAA expanded the camera program to Colorado in 2020. Under an agreement with the state, the FAA assisted with the installation of 52 cameras in 13 AWOS stations. Colorado subsequently took ownership of the equipment and all responsibility for maintenance.

At top right is a still image from one of the weather cameras at La Veta Pass, Colorado, with a “clear-day” exemplar below showing the distance and elevation of prominent features. As the image reminds us, it’s important to note that weather camera imagery is advisory-only—you can’t use it as an official weather briefing—but they are quite valuable in depicting what the reported conditions at each site actually mean, even if you’ve never been there before.

You can access the weather cameras in Alaska, Colorado and Canada online at weathercams.faa.gov.

A FAMILIAR OUTCOME

Three years later, on July 10, 2018, Taquan Air crashed into Jumbo Mountain nine miles from Hydaburg. The charter was flying a regular route for the company, transporting 10 passengers from Steamboat Bay Fishing Club on Noyes Island to Ketchikan. Departing at 0745, it was the second of three company flights, each of which took different routes back to base. The closest weather to the crash site, in Hydaburg, included an overcast at 1700 feet, light rain and mist, with visibility of five miles. The area forecast included an overcast at 5000 feet, isolated broken ceilings at 2500 feet, light rain and “mountains obscured in clouds/precipitation.”

One of the passengers, a private pilot, told investigators the weather was marginal, “barely VFR,” as soon as they took off. At one point, the pilot turned around and attempted another route; the passengers then began texting each other of their concerns as they went in and out of the clouds. While they discussed asking the pilot to land and wait out the weather, they encountered heavy rain and the pilot attempted to turn around again. The aircraft impacted Jumbo Mountain at about the 2500-foot level at 0835. A passenger was able to call 911, initiating a rescue by the U.S. Coast Guard, which was delayed, according to rescuers, due to “low cloud ceiling and poor visibility.”

This investigation, like that of Wings of Alaska, also turned up concerns about operational control and risk assessment. The NTSB discovered almost immediately that Taquan’s DO did not reside in Ketchikan but 775 miles away in Anchorage, where he was also the Director of Operations for a second Part 135 operator (one of the state’s largest). He also worked part time in Seattle as a simulator instructor for Alaska Airlines. Investigators determined that the company suffered from his absence as, contrary to the Taquan General Operations Manual, numerous senior pilots simply assumed operational control as needed. In his interview, the Chief Pilot made it clear that he was overwhelmed covering both jobs. By his own accounting, he monitored pilot performance, did all the pilot hiring, maintained the records and scheduled the pilots, including training and check rides, made go/no-go decisions on a daily basis and also decided which route pilots should take. “What else do I do?” he asked investigators rhetorically. “Everything.”

In this case, the NTSB could not prove that the absence of the Director of Operations directly impacted the pilot’s decision to continue flying VFR into IMC so the probable cause cited only the pilot’s actions. But in a scathing passage in the final report, investigators did note, “Based on the FAA’s inappropriate approval of the DO, the insufficient company on-site management, the inadequate operational control procedures, and the exercise of operational control by unapproved persons likely resulted in a lack of oversight of flight operations, inattentive and distracted management personnel, and a loss of operational control within the air carrier.”

Under Part 91, applying risk-management principles is not formally required. Some of the ways the FAA mandates risk-management for Part 135 operators include:

Crewmember Qualifications

A minimum qualification for a Part 135 pilot is a commercial certificate and, often, an instrument rating.

Procedures And Training

Crewmembers are required to undergo training in operating procedures and recurrent training more often than every two years.

Weather Reporting

Under IFR, Part 135 flights may not begin an approach unless the destination airport’s observed weather meets certain requirements, which may exceed published minima. —JB

Colleen Mondor is a private pilot with degrees in Aviation Management, History and Northern Studies. She has written about, and worked in, Alaska aviation for 25-plus years.

AFTERMATH

Three months after the Wings of Alaska crash, SeaPort Airlines sold the company; its new owners went bankrupt in 2016, as did SeaPort later that same year. Taquan crashed twice more in 2019, a midair collision in Ketchikan and crash on landing in Metlakatla, which collectively left eight people dead and nine seriously injured. Both of those accidents are still under investigation and the company continues to fly. (It did hire a new DO in 2018.)

In the crashes of Flight 202 and Jumbo Mountain, the pilots made questionable decisions to depart and continue flying in deteriorating conditions. There were many significant failings outside of the cockpit, however, from training in decision-making and risk assessment to lax operational control. There was little communication about weather conditions or decisions to be made based on weather and no one noticed that these critical conversations were not taking place.

The lessons for both Part 91 and Part 135 operators include formalizing the decision-making process, accurately assessing weather and ensuring regular training in these as well as piloting skills.