-by Jay Apt and Paul Bertorelli

For pilots pursuing an instrument rating, the ultimate goal is to get to a place where weather is no longer a showstopper but just another thing to plan around. The reality, of course, is that having an instrument rating only complicates the go/no-go decision with more factors and more hazards – especially during the winter when ice is ever a risk. Some winter weather is simply unflyable, no matter how much de-ice gear, bleed heat and glycol you have at your disposal.

On the other hand, most winter weather can be negotiated in some way with a thoughtful plan and, above all, an escape hatch if things start to unravel. Nonetheless, all the planning in the universe wont get by the fact that sometimes you just cant go. In this article, well look at two decisions on the same night, one pilot arriving into nasty winter weather, the other attempting to depart.

On the weekend after New Years 2003, a classic Noreaster marched up the eastern seaboard, bringing snow, rain, freezing rain and moderately high winds. The airlines kept flying, barely. General aviation came to a near standstill but, as is often the case, there were ways to thread the needle. Jay Apt describes how he arrived at a go decision, Paul Bertorelli explains why he stayed on the ground.

———-

GO

We had spent five days with relatives in the Florida Keys and another five in Grand Cayman. After re-routing to avoid some energetic TRW lines on the southbound legs, I had no illusions of an easy ride back north in an El Nio year.

Cayman has a good weather shop like the FSSs of old, so I dropped in on them the day before departure to supplement what Id been seeing on the Weather Channel and my laptop.

The Cayman folks dont have much winter expertise, so I called the direct number for Altoona FSS as well. It looked as if the first problem would be a pair of cold fronts in south Florida that might put both Key West and Ft. Pierce below minimums in heavy rain, so I spent some time on the phone with customs making sure we could land elsewhere if required.

We had planned the flight for a Friday just in case we needed to spend a night on the road, and still unpack in a relaxed way when we got home. I told the family that, depending on the Pittsburgh weather, we might be visiting a motel Friday night. They are used to that, and I figure their flexibility is the best safety system on our Beech 18.

Getting Underway

Wheels up from Grand Cayman into a low overcast Friday January 3 was at 8 AM EST. The cold fronts were north/south just east of our route over Cuba, and we heard all the complaints from the pilots in the Bahamas as we turned off the radar going into Ft. Pierce with nary a bump.

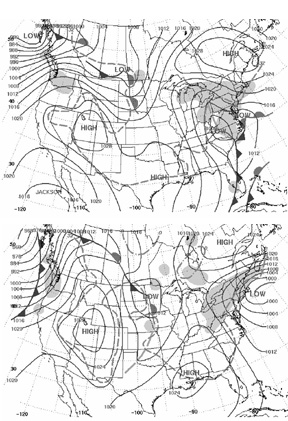

Id been keeping track of the coalescing lows in the Carolinas and had considered a number of routes up from Key West to Ft. Pierce north, and settled on one pretty much north from Ft. Pierce when it looked as if the fronts were moving east quickly.

We have gone from Ft. Pierce to Pittsburgh nonstop a few times in the past, but with headwinds and home plate on the northwest side of the low, I wanted 3 hours of reserve when we got there, so we stopped near Augusta, Ga. – cheap fuel and motels if we decided to stay the night – for gas and a peek at the radar.

A look at the FBO computer showed that the precip had started to leave our route except in southern West Virginia and seemed to be moving east out of the Pittsburgh area, but slowly. The Pittsburgh forecast was 600 broken, 1,500 overcast, 1 in light snow.

The important features for post-frontal icing are well stated in Robert Bucks Weather Flying: after an east coast cold front, there is usually a hundred miles of clear air, west of which icy air-mass stratocumulus decks build in the unstable new cold air.

The tops are generally highest closer to the front, but a normally aspirated piston can generally get on top. Checking the pireps with a helpful briefer, the tops seemed to be at 6,000 feet, with icing reports only in the descent or climb. So the plan formed: Stay in the clear or between layers until descent, then fire up all the ice protection.

Id bought the Beech 18 after picking up an inch of unforecast ice during an approach into Pittsburgh in my A36 Bonanza one May afternoon. Sure, I could have put a TKS system on the Bonanza, but I was looking for another challenge and the family loves the huge cabin with its wide aisle and potty in a separate room. Me, I like the S-TEC autopilot, radar, anti-ice, GPS, HSI and the 1,288 pounds of payload with full tanks.

De-icing Equation

Establishing known icing certification for an aircraft first produced in 1937 is best done before starting the motors. When I bought the BE-18, I spent some time researching and came up with a 1969 letter from the chief of Beechs Engineering and Manufacturing Branch to the FAA. It states We consider the Beech Model 18 Aircraft approved for flight into known light or moderate icing conditions when the following listed equipment is installed and operative… and lists the items – including boots, prop and windshield alcohol, heated fuel vents, the wing ice light, alternate static source, hot pitot, defroster blower, wipers, and approved antennae, but interestingly not a heated stall warning.

Good to go with this stuff but is it smart? Suppose we get over Pittsburgh and things have gone severe or below mins? From our fuel stop here, it will be 3:15 to get over the Allegheny County airport and we have 6:20 on board (worst case with full heater use, which I figure we will have tonight). Columbus, Ohio, is looking good and was less than an hour from Pittsburgh the last time we did it on the airways, so it made a handy and safe alternate.

After a quick turn, we were on top at 7,000 on the way north with the outside air temperature at -4 C. We ran into a few tops and got a light dusting of rime, so we climbed to 9,000 feet and were in the clear before the sun set.

The FSS folks were helpful in our quest to keep track of the weather all along the way, so I had a good picture of what the Pittsburgh area was seeing and that Columbus and Huntington, W. Va., were VFR if Pittsburgh went down. Farther afield, Roanoke and all of Kentucky were holding up nicely. With three hours of gas over Pittsburgh, we could reach all of these – as long as we made the decision while we were still on top.

I got the AGC FBO on the radio at 100 miles to find that the runway and taxiways were clear. In the early 1970s, I did my solo XCs in New England, landing on snow-covered runways, but I always respect the effect of a contaminated surface, especially since the forecast called for a 20-degree crosswind gusting to 15 knots. The Twin Beech has two tails to help you weathervane, so I was happy to hear it was not a sloppy night. Heavy snow on approach can really distract you from the runway lights at night, too. Got to love that tracer effect from the landing lights.

Sunset was over northwest Virginia, and Id known in the planning that it would be moonless. The stars disappeared near Clarksburg, but it was easy to see that we were between layers; funny how well your eyes can pick up shades of darkness.

We passed a plan to Center that we were going to stay at 9,000 feet until 20 miles from the IAF at Allegheny County due to ice in the descent, and they passed that along to PIT Approach. Approach has more flexibility taking you into GA fields than into the commercial fields, and I made it clear that we planned to use a rapid descent. I reviewed what de- and anti-ice gear should be turned on in the descent: full prop and windshield alcohol, full defrost beforehand, manifold heat at the top of the green on the intake heat gauge beforehand.

The heated pitots had been on at takeoff. I did not have a clear plan for cycling the boots, but turned on the ice lights (outboard-facing from the nacelles on each wing) periodically.

Rachel, our 11-year-old, likes the right seat and read the approach and landing checklists when I called for them, saying approach [or the pertinent one] checklist complete just like a pro. Wed practiced this on the earlier legs and I told her it would really help on the approach.

We verified that other airplanes were getting in before initiating the descent. The plan was to stay on top until real close in, and then do a rapid descent to pick up as little ice as possible. At 20 miles out we initiated a descent at 1,000 fpm per the plan and got light to moderate rime, as expected. Approach blew the vector from ILS base to final and almost sent us through final. He said hed take us around for another. I told him Nope, not in ice, lets make this work and we intercepted OK.

The Allegheny County observation a few minutes prior to our landing on runway 28 was: 29009G14KT 270V340 5SM -SN BR OVC007 M02/M03 A2988 RMK CIG 006V010. We saw the lights at 600 AGL, so it was an easy approach.

How Id Do?

Here is my self scorecard: OK points for getting gas and going north on the basis of tops reports; OK descent planning; minus points for not noticing that the base-to-final was going to be late; minus for not doing a boot cycle sometime. (We landed with a third of an inch of rime on the leading edge.) Big minus for adding the second notch of flaps over the threshold.

It was the first real ice wed picked up in three years in the BE-18, and it handled it very well. But it could have paid off badly in the flare with the flaps at 30 degrees. Theres a good NASA tailplane icing DVD available that makes the point that you should use minimum or no flaps on an icy approach.

Having the general picture in mind – that stratocu will dominate the area after a winter cold front has passed – allows you to fill in the biggest gap in our forecast/pirep system (where are the tops?) and to make a flight like this one – as long as the alternates remain good options and you have managed the family pressure to land at the intended point.

-Former astronaut Jay Apt is now Executive Director of the Carnegie Mellon Electricity Industry Center.

———-

NO-GO

Sometimes, I think everything I know about the weather I learned from The Weather Channel. And also from carefully briefing – and rebriefing – more than a handful of trips I never flew. If theres a lesson to be learned in failure, the wisdom of the ages may lie in not even making the attempt.

So it was for me on January 3, 2003. I absolutely, positively had to be in Florida on Saturday morning, January 4 for an important meeting. The day before, I had just retrieved the airplane from the avionics shop following a major upgrade and a repair of the alternator. We had wrung the systems out carefully and everything checked out, but I have a fundamental mistrust of airplanes fresh out of maintenance. If I can avoid departing in low IMC or at night – or both – in a freshly repaired airplane, I will. After all, who needs that worry on top of dealing with fierce weather?

The Set-Up

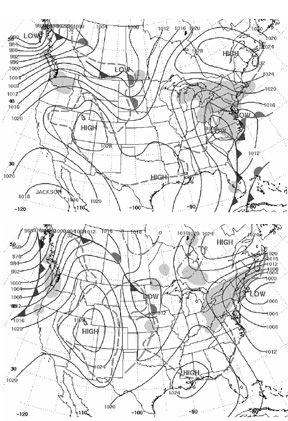

Speaking of weather, I had watched the long-range forecasts all week and what had originally been described as a chance of flurries in domestic forecasts ballooned into a full-blown Noreaster by mid-week. It was a classic system; a pair of lows converging off the eastern seaboard and sliding up the coast from the Carolinas toward Boston. There was plenty of cold air and plenty of moisture, so clearly there would be rain, ice, snow and wind. The only question was who would get how much of each and where.

In retrospect, if I could have departed Thursday night, the trip would have been doable. The weather was dry and cold with marginal VFR in snow showers. But Id need to stop in central New Jersey to pick up a colleague who couldnt get away until at least noon on Friday. That gave the lows time to get cranked up and start spewing an icy mess from Maryland to Massachusetts.

Having lived in New England for 20 years, Ive seen my share of Noreasters. They are not always unflyable for, in the end, theyre nothing but low-pressure systems with a unique, characteristic track. A weather researcher once told me this pattern occurs in only in two places on the planet, off the Carolina coast over the Atlantic and off the Chinese coast over the Yellow Sea. The ancient mariners called them Hatteras lows and Shanghai lows, respectively.

In order of seriousness, Noreasters will produce icing – possibly severe – high surface winds, turbulence, snow and low-vis. How much of each depends on what path the low takes and what the pressure gradient is. By Noreaster standards, the January 3 storm was wet but the gradient was less impressive than other storms of its type.

Obviously, for any airplane but especially for an airplane with no de-icing equipment, icing is the top worry. Id be flying a Mooney 231 that is equipped with a hot prop but no other icing gear. Departing into freezing rain at the surface is a non-starter, as is arriving in it at the destination. Snow, even heavy snow, is less of a concern as long as it doesnt reduce the vis below minimums or close the airport to departures and arrivals due to runway contamination.

The Pink Band

Because they draw moisture from the relatively warm water, Noreasters have a rain/ice/snow transition band, depicted by a pink area on Weather Channel graphics. The band is always on the south or warmer side of the low. By Friday morning, the low had moved off the Jersey coast and the ice transition area appeared to be about 60 miles wide, extending from the Jersey/New York line into the central part of the state. South of that, it was all rain.

Unflyable in a non-deiced airplane, right? Not necessarily. Freezing rain and ice is often a surface event, as liquid water falls through below-freezing air trapped at the surface. Often, a Noreaster will pump warm air aloft and, indeed, that was the case. A couple of pireps I saw reported temps +3 to +5 degrees at 4,000 feet. On the other hand, there were so many reports of light to moderate mixed icing, that both the size of this warm air pool and the actual temperatures were suspect in my mind.

If you can depart on the cold side of the low, where the precip is all snow, you can sometimes climb high enough to get above whatever ice there might be and continue on your way. The problem with this trip was twofold. To get to New Jersey, Id have to transition New York airspace and ATC allows westbound traffic only at 4,000 or 6,000 feet in piston single. That altitude could easily be in a rich vein of supercooled water. Second, Id have to land in Trenton to pick up my co-pilot. And that would mean descending through potential freezing rain.

The surface temperature at Trenton was above freezing at 4 degrees C and was forecast to remain there through most of the day. That meant no freezing rain there, but not reliably warm enough to wash off any ice Id pick up during the descent and the approach. It might be doable but was hardly what Id call an appetizing challenge. The important question was how much icing was really out there?

Ugly Pireps

In a system like this, the forecasts dont count for much. Pireps paint the most accurate picture of whats really happening. And the picture wasnt pretty. Throughout early Friday, WeatherTap showed about a dozen pireps for New York State and New Jersey, with a handful for the New England states. To the west, near Pittsburgh, there was an urgent pirep from a Cessna Caravan reporting severe mixed icing. That didnt particularly alarm me because the air mass that far west was much colder than Id have to contend with. I was blindly hoping the low had warmed things up along the coast.

Another theory shot to hell. The pireps showed light to moderate mixed icing from about 4,000 feet well into the teens. Worse, all of the pireps were from air carriers or GA jets, which I am spring loaded not to trust. My view is that pilots of these aircraft tend to underreport the severity of icing because its largely a non-issue for them. Whats light icing to a 757 may be moderate or severe for an aircraft not capable of climbing through it in three minutes or burning it off with bleed air.

The utter absence of light-aircraft pireps indicated to me that either no one was gutsy enough to give it a try or they were too scared to offer pireps. Neither was good. (The third possibility, of course, is that no fool in his right mind would even consider departing into such a mess and I was about to pitch my tent in that camp.)

At the departure end – Waterbury-Oxford, Conn. – the weather was acceptable. A 1,000-foot ceiling in light snow, wind out of the east gusting to 20 knots; clear and mostly dry runway. But that icy band in New Jersey simply wasnt going to move or warm up. In the end, it was the insurmountable factor that finally moved the decision from the maybe column to the no column.

The Finer Points

There is, of course, another aspect of the go/no-go decision: the legality. Bluntly, theres no way an aircraft without known ice certification can make a flight like this legally. As weve reported time and again, the mere appearance of icing in a forecast means that in departing into such weather, youre automatically exceeding the airplanes certification limitations unless you have icing protection, ergo, youre violating the FARs.

Yet anyone who flies during the winter when ice is in the forecast – which it almost always is – plays the odds that the icing wont be serious enough to pose a real threat. Perhaps the temperature is warm at the surface, the tops are low or pireps suggest the forecast is wrong. Whatever, if the odds of completing the flight without serious icing appear good and there are solid escape hatches, most of us launch into the clag and take our chances.

That wasnt the case in this storm. The bolt holes simply werent there. There was serious widespread icing and simply no plausible deniability if the trip unraveled and ended up with an emergency declaration to divert … or worse. The fact that Id have to transition busy New York airspace with limited altitude flexibility – make that no altitude flexibility – meant Id be at the mercy of ATC and the weather, with not many options.

Important trip or not, I cancelled the flight by midday Friday. The Florida meeting would have to wait. The next day, I extracted the airplane from an ice-bound hangar and arrived at my destination exactly 24 hours later than planned. All things considered, thats not bad. Its certainly far better than some ugly alternatives I can easily imagine.

-Paul Bertorelli is an ATP/CFII and editor of Aviation Consumer.