I’ve long maintained that one of the most dangerous things in general aviation is two pilots trying to fly the same airplane at the same time. The problem is that, eventually, one pilot will come to think the other one is flying the plane while the second pilot knows they’re not flying it. The inevitable result is that no one is paying attention. This realization is one of the reasons commercial crews long ago adopted the pilot-flying/pilot-not-flying designations and mandated that one of the crew perform actions while the other verifies the action was correct and appropriate. But it frequently rears its head in less-formal situations when two pilots are at the controls, like advanced training.

According to a 2014 publication by AOPA’s Air Safety Institute, Accidents During Flight Instruction: A Review, “In both airplanes and helicopters, fatal accidents were more common during advanced instruction than in primary training, and happened more frequently during dual instruction than on solo flights by student pilots.” In fact, according to the publication, “More airplanes crashed during recurrent training and new-model transitions than in pursuit of additional ratings or certificates, but fatalities were most common during instrument training.” Why is advanced training riskier than the primary flavor? Is it because there are two pilots at the controls, or is it something else? If so, what? Regardless, what can we do about it?

WHAT’S THE RISK?

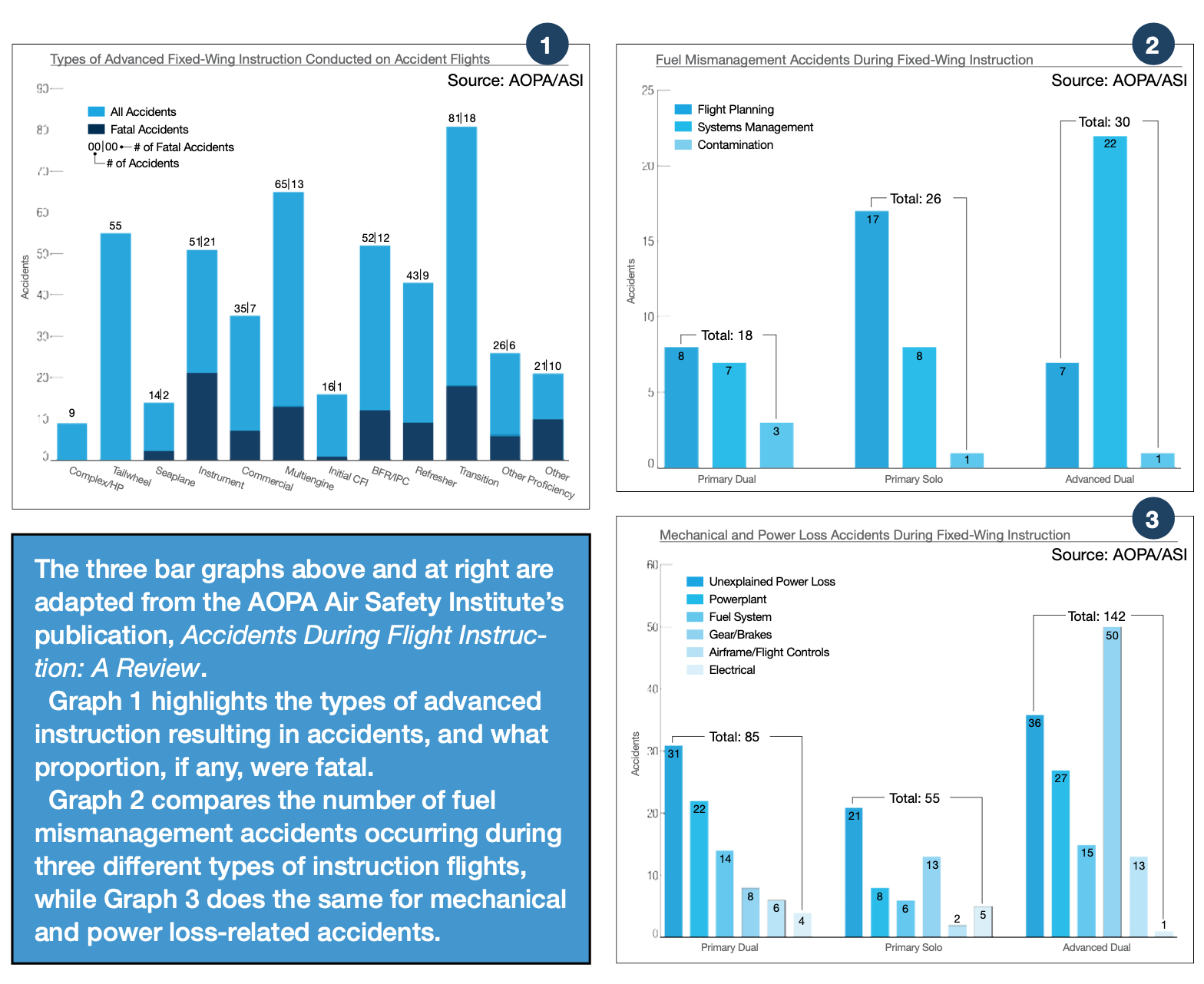

The additional risks in advanced flight training seem to go beyond just having two rated pilots at the controls. The bar graphs on the opposite page provide some of the details, and show in Graph 1 that instrument work and transition training lead the pack, with multi-engine, BFR/IPC flights and refresher instruction rounding out the top five. The selected graphs also highlight that fuel mismanagement (Graph 2) plus mechanical problems and power losses (Graph 3) are prevalent when conducting advanced training. I’ll get back to Graph 1 in a moment, but let me focus briefly on Graphs 2 and 3 first.

With respect to fuel mismanagement and Graph 2, it’s incredibly interesting that two certificated pilots can’t seem to remember to switch tanks—the basic reason for a mishap resulting from fuel systems mismanagement. In other words, fuel was available, but no one positioned the fuel selector(s) appropriately so it could be used. While it’s always dangerous to make generalizations, I’d bet a tank of 100LL that one pilot in these events was depending on the other to manage the fuel. The corollary is that neither pilot took it as one of their responsibilities to verify the selector(s) were properly positioned.

Graph 3, meanwhile, tells us something similar, but about powerplant management and transitioning to different airplanes. In particular, Graph 3’s tallest bar is dedicated to mishaps involving landing gear and brakes. It’s no great feat of imagination to posit that these accidents occurred during transition training to a retractable airplane, perhaps even one of the older models that lack a wheel braking system accessible from the right-front seat. Less likely but also possible is a flight instructor candidate encountering muscle-memory problems when trying to do it all from the right seat. Regardless, these are just two areas in which advanced training typically leads to a greater number of accidents than primary instruction. But let’s look at Graph 1 again, and think about how to prevent some of the accidents occurring in five specific advanced training operations: instrument, transition, multi-engine, BFR/IPC flights and refreshers.

INSTRUMENT TRAINING

According to the AOPA/ASI publication, few of the fatal accidents during instrument training “were ascribed to deficiencies in flying instrument procedures.” One takeaway is that safety pilots/instructors do a lousy job of looking for and avoiding traffic. The AOPA/ASI notes that five of the 21 fatals were mid-air collisions, “including one between two airplanes engaged in hood work.” By contrast, “there were only nine fatal mid-airs in all types of advanced training.”

The remainder of accident causes were rather too familiar: takeoff or landing stalls, fuel mismanagement (both starvation and exhaustion), plus CFIT or in-flight losses of control, our old friend LOC-I.

What does this tell us? One thing is that IFR training—and perhaps advanced training itself—can immerse both pilots so deeply in the instrument panel that at least one of them forgets to look outside, for both traffic and terrain. Also, it seems inexplicable that an instrument-training mission would end in fuel mismanagement. There are two certificated pilots aboard—surely one of them is responsible for checking the fuel tanks.

TRANSITION TRAINING

Frequent contributor Tom Turner has done some deep dives into accident data over the years. One thing he’s identified is what we might call the disproportionate presence of a recent registration change for an accident airplane. Basically, registration changes occur because ownership changed, and the basic theory is that transitioning to a new airplane is another advanced training area that sees a relatively high number of accidents. It’s not a great stretch of imagination to figure this out.

One of the pilots is new to the type. Duh. That means systems knowledge, muscle memory and the ability to predict flight characteristics and behavior is totally absent from the left seat. The pilot may be ace of the base, but it’s a new machine to them, with its own quirks, and they have no history against which to gauge what is normal and what isn’t. Ideally, the CFI has a bunch of time in the type and knows its systems and quirks well. But that isn’t always the case.

When I started flying my Debonair, I had plenty of A36 time, but no experience in a short-body Bonanza, so the insurance company wanted two whole hours in a Beech 33 or 35 before I was covered. Getting two hours of dual was easy, but I didn’t really learn to fly the Deb until I took a type-specific course from the Beechcraft Pilot Proficiency Program. There was classroom work and airwork, including emergencies, with CFIs who knew the airplane. Without that training, my first few hours in it would have been much riskier.

Instructors working to help a new owner learn the airplane need to step up their game. CFIs: Spend some time before the flight to review the manufacturer’s documentation, especially the equipment list and any systems or operational recommendations that result. Take a close look at the airplane itself. Just because it has a “fresh annual” doesn’t mean everything is as it should be; the new owner probably isn’t able to tell the difference.

MULTI-ENGINE TRAINING

It’s no great surprise that fatal accidents during multi-engine training typically involve one-engine-inoperative (OEI) flight. According to AOPA/ASI, “Nine of 13 fatal accidents involved losses of control in flight, and at least seven of those were in single-engine flight (including two which lost engine power due to fuel starvation).” There also was an instance of fuel exhaustion, of course.

There’s been a lot written about multi-engine training here and elsewhere over the years. A lot of it is true. As the FAA’s Airplane Flying Handbook (FAA-H-8083-3B) says, “The basic difference between operating a multiengine airplane and a single-engine airplane is the potential problem involving an engine failure. The penalties for loss of an engine are twofold: performance and control…. Attention to both these factors is crucial to safe OEI flight.”

One of the things about operating a conventional twin on one engine many pilots may understand intellectually but have a problem putting into practice is that OEI control often can be restored with one simple action: reducing power on the “good” engine. Yes, you’ll have to accept a loss of altitude, but if you’ve lost control or are about to, that’s going to happen anyway. It’s best when you have enough altitude that it doesn’t matter.

The other thing is to recognize there is no go-around from a balked landing with the typical light twin, especially once the gear and flaps have been extended. You’re committed and—now more than ever—need to manage the airplane’s energy.

BFR/IPC/REFRESHER FLIGHTS

I’ve lumped these categories together because I think they often share two characteristics that increase risk. First, and to a greater extent than other advanced training, they tend to involve a pilot who already knows how to fly the airplane. They’re typically not doing IFR training per se, transitioning to a faster airplane or learning to fly a twin. There are exceptions, of course, since many pilots use the BFR or a refresher flight as an opportunity to check out in a new-to-them airplane.

Regardless and while the AOPA/ASI publication doesn’t delve into the reasons, some of them seem obvious to me: the pilot somehow deceives the CFI, either intentionally or not, into thinking he or she is more competent and prepared than is really the case. It’s also possible the CFI isn’t familiar with the aircraft and isn’t aware the pilot is doing something wrong.

It also would be interesting to know to what extent the pilot and the instructor socialize outside the cockpit. In such situations, there’s always an undercurrent of familiarity and misplaced trust on the part of both occupants, who are friends, leading to complacency. And complacency seems like it should be the underscored word when considering accidents involving these types of training flights.

The FAA’s Airplane Flying Handbook (FAA-H-8083-3B) tells us, “During flight training, there must always be a clear understanding between the student and flight instructor of who has control of the aircraft.” Toward that end, the agency developed what it calls a “positive three-step process in the exchange of flight controls between pilots is a proven procedure and one that is strongly recommended.” Here’s the FAA-approved procedure:

This should be the norm when transferring control in either direction, of course, and not just when instructing. The AFH adds, “Numerous accidents have occurred due to a lack of communication or misunderstanding as to who actually had control of the aircraft, particularly between students and flight instructors. Establishing the above procedure during initial training ensures the formation of a very beneficial habit pattern.”

ADVANCED LESSONS

Since the FAA typically will consider the flight instructor to be the pilot responsible for the flight’s safe outcome when a training operation is conducted, a lot of the safety shortcomings during advanced training fall squarely on the CFI’s shoulders. But these are operations involving two pilots, and each has a role to play and certain responsibilities that go with their role. For example, it’s not enough to presume the instructor is looking for traffic or ensuring terrain clearance when you’re under the hood. When he or she is trying to help you program the GPS, no one is looking outside.

Whenever there will be two pilots at the controls, a pre-flight briefing is necessary to clearly describe responsibilities. One and only one pilot can be the PIC, while the other monitors. It’s also possible that both seats are occupied by someone placing greater faith in the other than is warranted. As someone once famously said, “Trust, but verify.”