I recently read Mr. Marcum’s excellent comments concerning the crash of JFK, Jr.’s Piper Saratoga II (Unicom, August 2016). As a pilot and flight instructor, and as a clinical laboratory scientist for over 50 years, I’d like to suggest there are additional factors that command consideration.

First, with no reported passenger in the right seat, was there an asymmetric load on the aircraft which was initially compensated by the autopilot? Could the pilot have experienced a runaway electronic trim malfunction when resuming manual control of the aircraft?

Secondly, could the pilot have been suffering from the combined effects of reduced oxygen availability compounded by hypoglycemia? Considering the flight altitude of 5500 feet at night, perhaps combined with either no evening meal, or a hurried high-carbohydrate snack, a low blood sugar concentration could have affected his responses.

Lastly, his stress level would have been off the charts. He apparently was experiencing the triad of job, marital and health pressures. Add to this an early Friday evening departure after experiencing New York City weekend rush-hour traffic. Did his coworkers notice his physical and emotional condition prior to departing Caldwell Airport? What were his wife and sister-in-law discussing in the rear seats—a possible source of distraction? Could a sudden nature call have increased the pressure to descend quickly?

My curiosity compelled me to fly his route under similar night and visibility conditions both on the Redbird FMX and Microsoft X flight simulators. The conditions proved, at best, to be very marginal VFR. In addition, both simulators suggested that the runway lights and rotating beacon at Martha’s Vineyard were not visible at a distance greater than four nautical miles—contributing to a “black hole effect.”

Almost two decades after this sad event, there are still aviation lessons to be learned.

Michael Sealfon

via email

Running Tanks Dry

With reference to Tom Turner’s excellent article on running fuel tanks dry (“Run It Dry?” June 2016), in 1997 we purchased a Cessna 210 and had a Shadin fuel totalizer installed. Soon thereafter, we intentionally ran each tank dry once, on successive flights. Each time, as soon as the engine hiccuped, we selected the other tank, so the engine never completely quit. We found the totalizer an excellent additional source of fuel-quantity information.

For a number of years, we lived above the cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean near the Santa Monica (Calif.) Airport (KSMO). On calm late afternoons, I frequently would see a beautiful red SIAI-Marchetti SF.260 glowing in the sun as it performed aerobatic maneuvers over the ocean.

In January 2009, I was at KSMO, inside my car with the windows rolled up, just a few hundred feet off the runway. I glanced up to see that same red Marchetti take off. At the end of the runway he abruptly yanked the plane nearly vertical. The pilot got the plane pointing back toward the runway, but didn’t have enough altitude; he was only about 300 feet agl at the start and less than 500 feet agl at the apex of his maneuver. He almost made it but instead pancaked onto the hard surface right beside the runway and instantly burst into flames. Both aboard were killed.

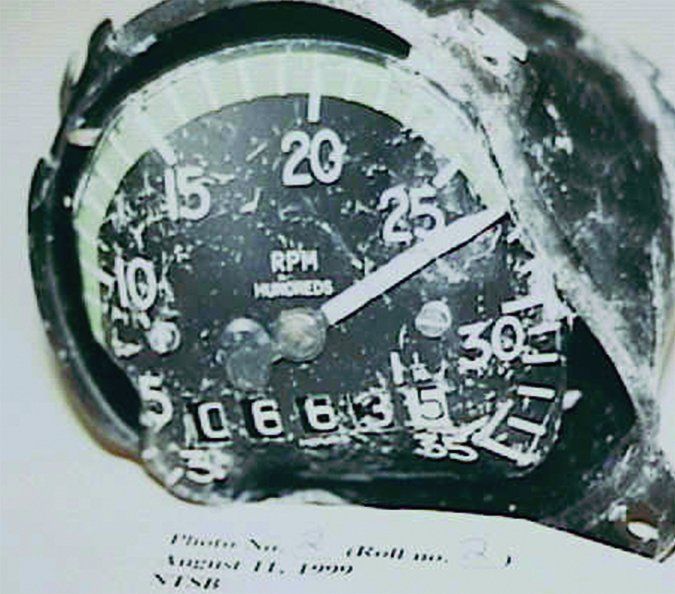

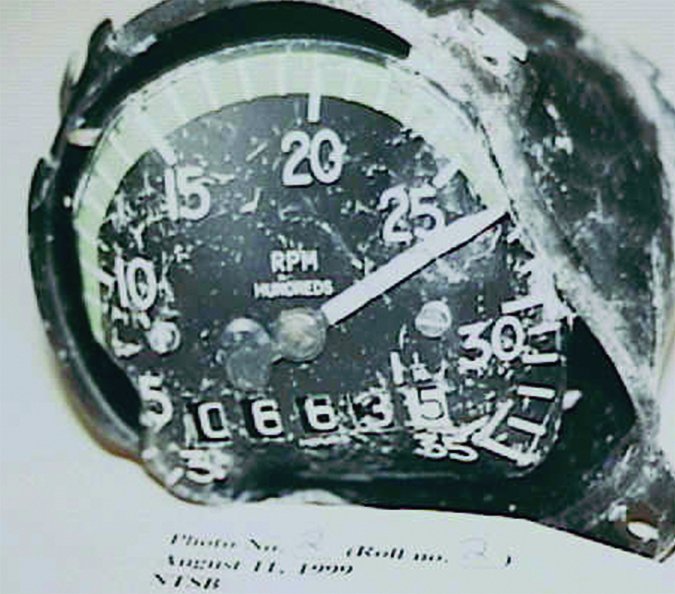

The NTSB final report details that the aircraft had previously been taxied back to its hangar (a week prior, by another pilot) using the right tip tank, as per SOPs for that airplane. Apparently the accident pilot forgot to switch to the left main tank, as per the POH, before takeoff, and the aircraft experienced fuel starvation shortly after takeoff.

What I will never understand is why the pilot elected to try to turn around instead of gliding straight ahead onto the golf course off the end of the runway (the same golf course where Harrison Ford crashed last year). He nearly turned his Marchetti on a dime. He just ran out of go-juice and altitude.